A catalyser of thoughts and experiences.

It’s been three years now since artists Sophie Vallance Cantor and Douglas Cantor moved to Berlin, a city that has provided them with a sense of isolation, turning out to fuel an honest and fluid production of their works. Sharing lives, studio, and experiences, Sophie and Douglas have constructed two quite distinct visual languages; yet one which allows a fluid conversation with one another. The bleeding of their practices welcomes an open discussion, in which the artist’s intermingle motifs and colours, re-appropriating certain elements from each other, with the will to push forward their artistic practice. To learn more about how they achieve this, we visited Sophie and Douglas’s shared studio space; a re-configured living-room area of their house; filled with cats, rugs, kitsch objects, and paintings.

Berlin, by Martin Mayorga

When and why did you move to Berlin? How has your work evolved since then, and what struck you about Berlin when you relocated?

SC: I moved to Berlin at the very end of 2015, having left my degree unfinished. Me and Douglas were unable to keep living in London due to the financial restrictions imposed on non European spouses and their British partners by the Conservative government. I moved alone, as Douglas couldn’t join me until a few months later, and stepping down in freezing, grey, Berlin in the middle of winter, honestly, felt a little like a nightmare. It was only after 8 or 9 months after moving that we finally found a more permanent apartment to live in, and I felt I had the mental and physical space to properly start making work again. In the time, subsequently I feel my work has completely transformed- the experience of tricky life circumstances has fuelled a much more honest production of work for me, I no longer feel clouded by expectations or judgement of what kind of paintings I should be making – what is trendy to make, what tutors like or dislike, or what I see other people making. I make what I feel like making.

DC: I moved to Berlin 4 months after Sophie did. After having to leave London, I went back to Colombia to organise my documents to able to join Sophie. I arrived to Berlin in the middle of the night at the end of winter, to an an apartment without any furniture that Sophie had managed to find for us, and I remember being very fixated on the lack of people in the street and how that made the city look so post-war. I remember that I was traveling with a painting I had made while in Colombia, that funnily enough would go on to being exhibited in London later on that year. Once we were back together, we spent the little money we had on a big canvas and paint, and we set to work on a big collaborative painting together, mostly with the intention to keep making work during the settling period. I spent most of my time in the first 6 months after arriving, trying to get a job and working on my sketchbook, as anyone will tell you, Berlin is a hard city to arrive to. Having to move here freed me as an artist, I think, it allowed me to shake off layers and layers of external pressures to do things a certain way, and set me on quest for honesty and fluidity in my work. It’s not so much the city, as the sense of isolation that came with it. I guess in Berlin I learned to paint what I want to paint.

Berlin’s overwhelming art scene, architectural majesty, and energetic vibe is what makes of this city a creative meeting point for art insiders. What is the role of the city within your practice?

SC: Oddly enough, for a long time, the overwhelming role of the city has been one of isolation. Finding yourself in a city where you feel like an uninvited outsider, unable to go back to the place you think of as home, definitely produces some challenging feelings. However, I think the harnessing of this isolation has turned out to be the making of us. We prioritised our time and limited money and space for making paintings over many other things…my paintings became the outlet for my anger, pain, grief and love. I can safely say it has been worth the struggle.

DC: I think that perception of Berlin is slightly skewed by the city’s history and the reputation that it gave it. I mean yes, these are things that are part of Berlin, but seen from the inside, the long Soviet-esque winters, contradictory interactions in the street, and titanic struggles with bureaucracy end up being more defining of the place. There’s quite a specific lifestyle that goes with Berlin that I don’t share, the result of this can be isolating, and isolation is a good condition for focusing. Another result of isolating yourself is that you are left with little to stop you from dealing with your own self, those ingredients mixed well, make for honest, powerful work, I think.

What is your routine like in the studio, usually? Does the fact that your studio space is located in your house control your daily practice? How do you find the balance between work and life?

DC: As it turns out, I learned I’m the kind of person that thrives in that kind of setting, I like to live with my work, there isn’t really much of separation within the two. I don’t have a set daily routine per-se. Time goes between buying materials, stretching canvases, going to work, priming, painting, showering, un-stretching, sketching, eating, writing, cleaning brushes… it’s just part of life, cooking dinner while the layers of primer dry, or taking a shower while ideas sink in. Eventually you become so familiar with the work surrounding you that you can switch off between staring at it for hours on end to completely forgetting it is even there. Only in some occasions does it turn out to feel like its too much, like when you find yourself in the middle of a challenging painting, then it’s imperative to leave the space and go for a walk and a coffee.

SC: Being constantly surrounded by paintings is a double edged sword, they become fused to certain moments in time, both good and bad, you can’t escape them even if you want to. But they’re also a comfort for me, they keep priorities present, even when life becomes difficult, there’s no excuse to not keep on painting when your canvas is right there. Berlin is boiling hot right now, and although we have a separate bedroom, its so small it sometimes becomes too hot to sleep in. The other day we dragged our mattress into the studio in search of relief from the heat. We lay in the half light together, looking at our paintings and suddenly we were able to see so clearly how far we have come, how unusual our priorities in life are compared to the a lot of people, and how maybe that in itself, is the most important thing.

Can you identify creative turning points or significant encounters in your career based in Berlin, so far?

DC: For me, Berlin has mostly been about the personal development, I was able to work in larger formats. I guess that deciding to switch to oil paint has been the major and biggest turning point in my practice, (I have Sophie to thank for that).

SC: Since moving to Berlin I’ve been asked to show much more often outside of the city than here! I feel there have been some really unexpectedly exciting moments in the last two years, like being interviewed for i-D, or being asked to be part of a show with the gallery T293 in Rome, but none of it seems to be happening in Berlin itself.

Berlin is home to one of the world’s most varied arts spot’s with long-standing institutions and art galleries. What is your position on the diverse art scene over the city? Are you somehow involved in it?

SC: As I spoke about before, isolation of our studio practise also extends to a sense of isolation from a lot of the art scene. Last February we curated HERUS, the first show of our work together in Berlin, in which we converted our apartment/studio into a gallery space open to the public. The premise for the show was based on the idea of us, the artists, taking authority over how we wanted our work to be shown without the need for endorsement from the institution. It did feel good to be part of the art scene and have the public, not just close friends come to see our work, and the idea behind HERUS is something we would like to continue, but it is not tied to a location or format, and we are open and hoping to collaborate in many different forms and locations in the future with artists, under this premise.

DC: I don’t think we are in any way involved. I feel you have to be a specific kind of person to navigate the networking required, `I think there is another way to make use of the city’s label though, Berlin is still a great place to actually make the work, you can still afford only working part time to pay for your rent and materials (just about), that is where we put our energy, I feel.

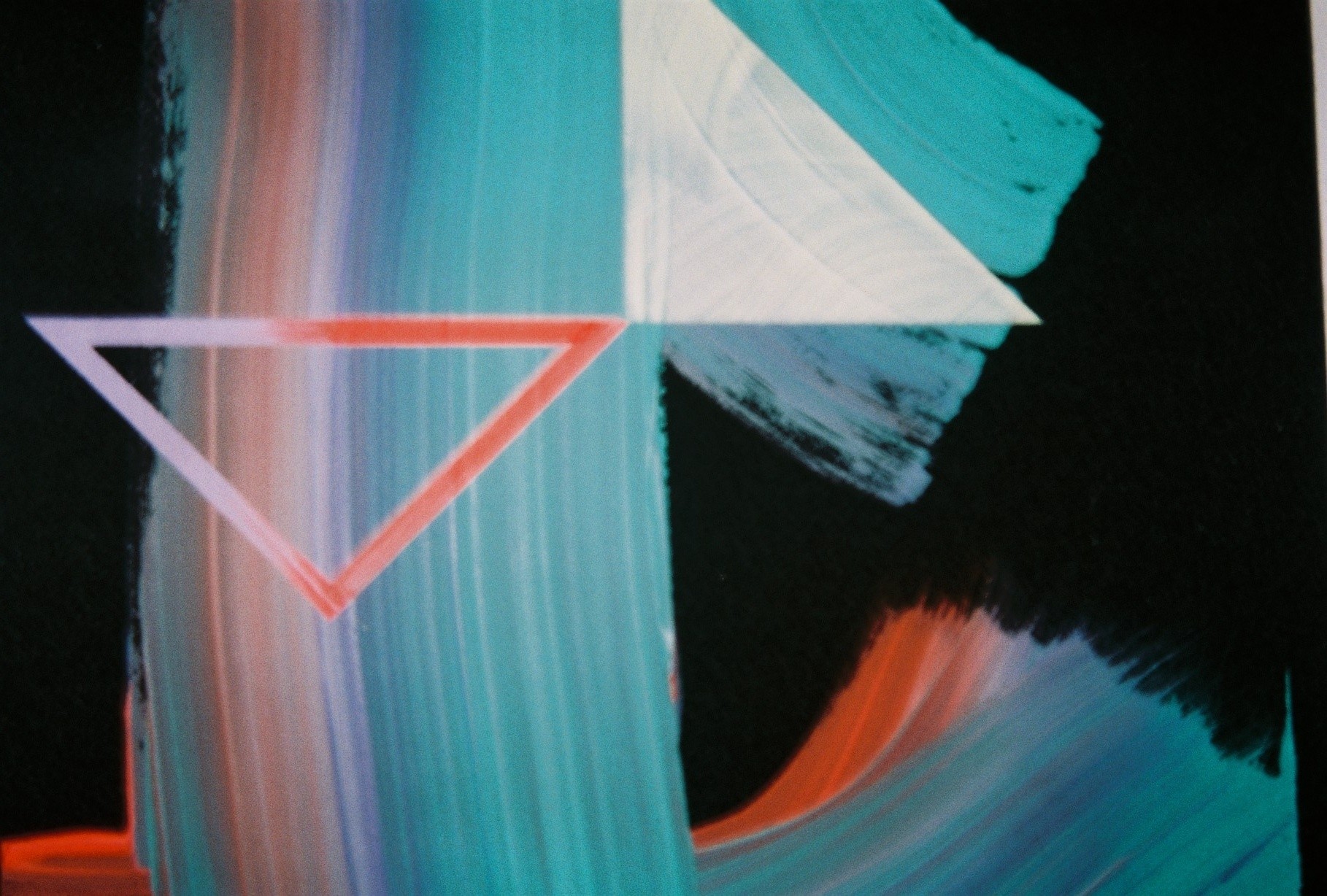

Work, by Vanessa Murrell

Would you both agree in saying that your practices are very personal to you, and resonate to that of a visual journal or a diary?

DC: That is exactly what my practice is to me, its a journal. Each painting is a catalyser of thoughts and experiences, they become engraved in time in the same way a tattoo or a smell becomes tangled with a feeling. You could also say it has a therapeutic intention, each painting sort of works as a page of a diary, an object that I can rely upon to be reminder of certain moments, epiphanies or answers I might have come across in my personal attempt to cope with existentially. All of this is not to say that my practice is solely personal. Although I indeed make work that fulfils my very specific human needs, I am aware of the fact that as public objects that paintings are, they have the power to resonate strongly with people that find themselves asking similar questions to those I’m asking myself.

SC: Yes, I would definitely agree that our practices are incredibly personal visual journals, however I feel that within that, we tend to naturally focus in on different sides of what that could mean. I feel we are very different people, who just happen to feel similar about certain things in life, and how we end up expressing things is framed very much by who we are as individuals. For me personally, I think there is a focus on vulnerability within my paintings, a portrayal of the side of the story that could easily be seen as something someone else might want to hide, or not shed light on, a search for truth, and empowerment through that. Humour also plays an important role. It seems to come with a sense of ease about it that can end up being incredibly evocative to portray complex feelings and situations.

I am amused by your collaborative practices – sharing studios, serving as mentors to each other, and often referencing one another in your works. Can you expand on this collaborative yet individual practice? In that context, does that make you –to some extent- an “artist collective”? Would you consider working individually at any point?

SC: The bleeding of our practices is a curious thing, and it’s something that has happened naturally as time has gone on. When you share a close working, living, creating, talking, eating, sleeping relationship in one space, it would be incredible if there wasn’t an exchange of elements taking place. I understand why for some people it could be something difficult to deal with, but for me personally, I kind of see it as two individuals with the same goals tangled together – I don’t necessarily see it as a collective in the traditional sense of the word, but if someone else sees us that way, I also don’t care. We are what we are, and were going to keep doing what we do. It would be interesting to see what would happen, if at some point we were making work apart from one another, but it’s not something I would necessarily seek out for that reason.

DC: I guess the point is that the collaborative aspect is not an element that originates from within the practices, we are collaborative in life. Our practices are very much individual, its we that are close. I suppose from the outside it can be seen as if it is a conscious part of what we do, but that is only because it’s difficult for anyone else external to our story to even start to imagine the many circumstances and decisions, both external and personal that have got us to this point. To say we are a collective would be to say that there is an intention behind it, but really we are just living life and making paintings, is just a crucial part of it for us both. What interlaces is the conversation of the everyday, the experiences, limitations and the ideals we share. In that kind of closeness (personal and physical) things start bleeding back and forth and it’s true that there is not an active effort to avoid it from happening but the reason is simple, because it would be unnatural and dishonest, we learn from it and from each other and embrace it as part of our moment in life. I have learned so much as an artist by being able to witness the development of such a powerful artist as Sophie, and I treasure that. But we are also adaptable, wink.

I am interested in your curatorial approach while in Berlin, having curated exhibitions of your works in your own house. In that sense, are you both concerned in exploring an alternative model to institutions?

DC: Alternative is exactly the point. As an artist, you rely on the institution to validate you and your work, but in this whole process, a huge deal of alienation takes place. In my opinion alternative institutions are the way to go, a democratisation of art that expands what social media has already started, that place value in a diverse variety of the qualities art has, and that better serve the needs of the diverse public that is not represented by the institutions we currently have. It’s all about options and conversation.

SC: I absolutely love the notion of exploring alternatives to the institution, especially at this crucial moment in history where there are so many things to be angry about, and also so many new ways to take back power. As someone who didn’t finish their degree, I realise that I really don’t need a piece of paper to be an artist. I think there is space for all sorts of ways to view art to exist, although the institution is very necessary… it is very flawed too, it represents a very niche (often very male, very white) cross section of the work being made, and it’s always good to challenge it.

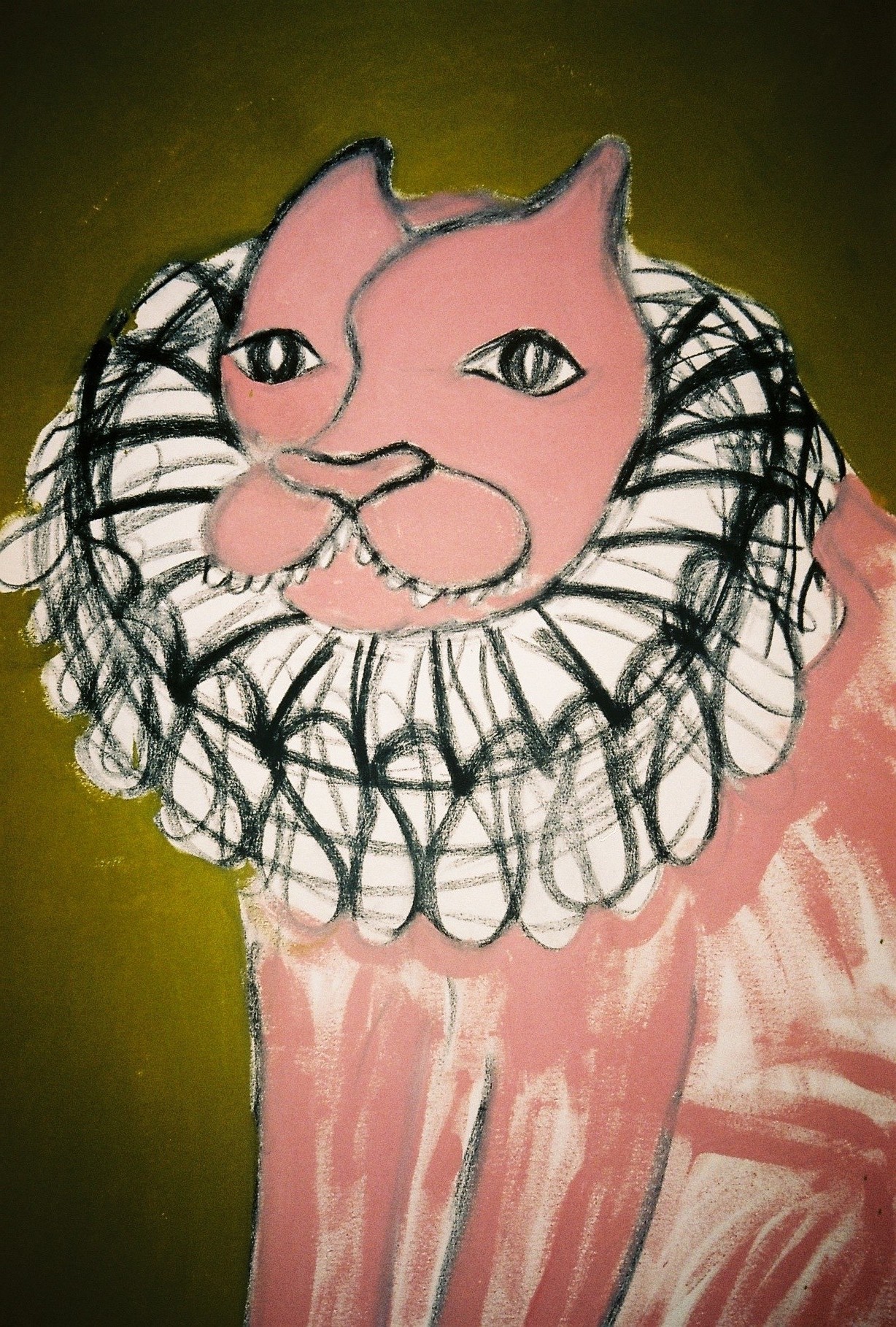

There are certain similarities in the way you both approach painting, such as in the use of text and image, the references to specific animals, the exploration of themes of identity and self-representation, the merging of high culture and low culture, the honesty of the works, or even aesthetic choices such as the color palette. In what ways do you identify similarities and contrasts between your practices?

SC: I feel that even though, at first glance especially, there are a lot of similarities in the elements that we both use in our work, it’s the way in which we individually use them that creates, two quite distinct visual languages. If you take drawing for example, the way I construct an image is most definitely through line, opposed to Douglas who almost sculpts shapes as if they were 3D. So the basis for each image, before there is even paint involved, is quite different. Something nice about the way we work with similar elements is that nothing is off limits, I never feel scared to steal an symbol or a colour from Douglas, there’s no territorial drama between us in that way, in fact, I really enjoy this part of our practise, as time passes and our practises move forward and we look back at the work we’ve made, it almost feels as if our two languages are having a conversation.

DC: The point is that we know the intention and trigger of the decisions, from a conversation, to a piece of advice, to mixing too much of certain colour, to an existential crisis, to an situational experience, so we are aware of the autonomy of each decision. On the occasions where elements are re-appropriated, there is no possession or jealousy or ownership, just the will to push forward, so personally, it turns into a compliment. Something curious though, is that while people might at first glance see similarities, (although I’m certain this is mainly because the context in which they see the work, such as within the same space) our work seems to speak to/attract very different people. And I think we personally are way more aware of the vast differences that may make the other one a more impressive artist.

Are you both concerned in exploring concepts of branding yourselves, along with ideas of becoming a product with your practices?

SC: The term branding is an interesting one, because it implies product, as well as identity. Identity is something fascinating to me both in my work and in my life, in fact, at this point it sort of blends into one. Although being a practitioner is about making paintings, being an artist is about the story as well. When you’re making such personal paintings you can’t really separate them from who you are, so they become part of your identity itself. I think the key difference that comes in to separate the terms identity and branding is to do with intention and honesty, I think if you have a sense of integrity when it comes to your work, and your priority is to always keep moving forward in your practice, no matter where it takes you, then you have command over yourself, and you are nobodies product.

DC: A brand is marketing tool for a product, but a household name is a certification of quality. I feel it is unavoidable to separate the art from the artist’s story, and this in time, turns the artist into something “brandable”. I don’t think I have a desire to brand myself, but I do hope that my story holds up to the work I make, so one day me and my work may become a household name, a seal of quality for the ideal I hold dear.

24.07.18

Words by VANESSA & MARTIN

Related

Studio Visit

Sophie and Douglas Cantor

Interview