Meet the artist who travels back to the Middle Ages to explore issues about where we are now.

By re-enacting scenes through an interaction with plants, earths and pigments, artist Sigrid Holmwood’s painting process develops into performance. Whether depicting plants, insects, instruments of torture, or peasants involved in daily activities, Holmwood questions predominant concepts of Western modernity and progress. We sat down with the Australian born artist at her plant garden located at Goldsmiths while she unraveled the influence that Norbert Elias, the 16th century Florentine Codex, Silvia Federici, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder have had over her latest work in her current exhibition ‘The Peasants are Revolting!’ at Annely Juda Fine Art, London.

BACKGROUND

When did you start to paint?

I think that most people paint as a child. So, I started as a child along with everyone else. I think it is more of a question these days of whether you continue painting when you start art school. I think that is often the big decision that people have. Certainly my parents were very encouraging, and they weren’t at all patronising, in fact quite critical – especially my mom. They bought me proper watercolours as a kid instead of children’s paints, and I think that made a difference because I can remember being enthralled to the tinting power of Prussian blue as a seven year old.

Why did you focus on painting?

I think a lot of people maybe stopped painting because of its long history, as it carries a large amount of baggage. For me, that is exactly why painting is interesting – because of all that baggage.

You adopt a “persona” and re-enact scenes from Old Britain. How did this practice come into your work?

I had a scholarship at the British School of Rome in 2003-2004. I found that the way you are surrounded by so much history made me aware of this feeling of being a re-enactor. Because of all the artists that had passed through Rome and the Grand Tour, I felt like I was somehow re-enacting the Grand Tour. Also, at that time, I was encountering some technical difficulties in my work, in some effects I wanted to achieve, and I realised I could only achieve them if I made the paint, because those effects weren’t possible with the paint you buy in tubes. So by doing that, I started to become aware of the idea of re-enactment. When I went back to Britain, I found online this woman online called “rent-a-peasant” – up north, in County Durham. I went to visit her, she is like “a peasant for hire”, for schools and education, where she will re-enact a peasant from different eras, and even bring historical livestock along. That opened up a lot. Initially, I was going to interview “The Tudor Group”, which I found particularly interesting because of the way they pushed things, it is not so much about re-enactment as a spectacle, but rather as a form of research in generating knowledge. So, I went to speak to them, I knew they would be at this re-enactors market, and I found myself joining their organisation – unplanned. I believe that experiencing things is the best way forward rather than just reading about things. So for me re-enactment is a form of research, rather than just a spectacle or an image.

The figure of the “peasant” is at the very centre of your work. Why did you adopt this figure in your work?

I am interested in the figure of the peasant because it is a figure within Europe that is used to construct modernity, in the sense that, this figure gets pushed into the past. Now, it also might be – subconsciously – something to do with the fact that my family in Sweden are farmers, from a farming background. So I have got that personal connection, and maybe a slight awareness that there is the countryside, there is this place where food is made, and that it is not just magically appearing in the supermarket wrapped in plastic. I feel like this figure is allowing me to explore many issues about where we are now.

PROCESS

You mentioned before that you don’t use tubes of paint, as you make your own pigments. I would like to know how do you research about these pigments and techniques?

There are several books, also information online. On the one hand, I tap into an online community of “nerds”, who dye with natural dyes, and who all have blogs where they post about their experiences. On the other hand, I also like to read the National Gallery’s technical bulletin, and conservation science reports on old paintings, because they give you a lot of information that cuts through the “bullshit”, as there are a lot of myths that grow up around the Old Masters’ techniques. When you get the scientific analysis, things are often a lot simpler that one imagines. Actually, I’m interested also in the way that conservation scientists use a form of re-enactment in their work, because quite often they will make a pigment recipe according to a historical text, and they use that as a model to test against, with the paintings. I think that they gain a certain insight, especially those conservators who are really open to this, because that experience gives you an experience of handling properties and a certain amount of insight into the decisions that those painters made in the past – such as why they chose to paint with certain materials. It is like a combination of hi-tech, techno-science, and an amateur form of research, and of course of re-enactment as well, and actually just trying things out, experimenting, going wrong, and adjusting the recipes.

And you also learn throughout communities in your travels.

Yes, exactly. I was lucky enough to spend a couple of weeks living with Dongba Shamans of the Naxi ethnic minority in Yunnan, in the Yulong Mountains in Southwest China. I was learning about how they make a paper there, from a local plant, and they use this paper to write their scriptures on it. It was a really amazing experience. One of the shamans was also researching the historic pigments because they had fallen out of use, so he was in a way doing exactly what I am doing which was – researching the historical, looking at landscapes, seeing what could be used, and also making his own pigments and pushing that aspect.

And did they teach you any new techniques that you didn’t know before?

Yes, I never made paper in that way before. I learnt a lot from that experience. When I came back, I had to respond to it. That plant that grows in the Yulong mountains doesn’t grow here, so I did Western style paper making, which is different to the Chinese style, because it has been adapted by the Arabs and the Moors, when they brought paper-making into Europe. They started making it from scraps of cloth instead of from the mulberry plants and daphne plants, that the Chinese used. One of the things I found fascinating about doing these travels and engagements with other communities is that there are things in common and also differences, but when you get down to the “nitty-gritty” like for instance, extracting indigo from plants, it is not a huge gulf of differences. There are various plants around the world that produce indigo, and all these people living all around these areas have worked out how to do it with their local plants, so actually the technique is very similar.

How do you relate this history with Norbert Elias works? You cite this sociologist, why did you chose this reference in your work?

The image of the peasant as a genre of Western European painting is something that appears really in 16th century. Before then you did not really have images of peasants in the fields. That moment is really linked to the development of capitalism in the stock market. It really happens in Antwerp – it was the site of the world’s first stock market and also the world’s first open art market, where you could just go along to buy a painting on spec, instead of it being commissioned. It was actually on the second floor of the stock market. When one thinks about the links between contemporary paintings and speculative high finance, you can just see that from history. Anyway, round this time you get an explosion of genres, the peasants, the landscapes, still life, and really artists are finding a “niche” in this market place. At the same time, I think that the image of the peasant was more than that: I think it was also used to construct a bourgeois class identity. Because there were these new collectors of art that weren’t the church or the aristocrats, but the merchant class that were getting rich from the colonial trade in Antwerp. What you see in these images is often that the peasants are uncouth, they are getting drunk, they are vomiting – a dog’s licking it. What Norbert Elias talks about is the history of manners, and the history of the disciplining of bodily functions that gradually happened over the course of the centuries, to create a middle class identity. The figure of the peasant represents what the bourgeois subject is not.

You state on your website that you use an “elastic definition of painting” and that an artist has to paint “decolonially”. What do you mean exactly by painting “decolonially”?

What I mean by the idea of painting “decolonially” is really that one should be aware that Western art history of painting is just provincial, it is just Europe’s history, and that there are various histories of painting that have different trajectories. For instance, how the image is treated, how space is treated, or even what representation is, and I think that we should not take any of these things for granted, that come out from the Western experience. What I don’t want to be is rehashing the modernist, sort of Picasso, using other cultures as a primitive inspiration – that, I am not interested in at all. It is more actually about sophisticated technologies and ways of thinking about space, about representation.

If there is need to paint “decolonially”, you also state that the peasant is a transnational figure.

I say that partly because the history of the figure of the peasant in Europe has also got this ugly side to it. It was evoked in very nationalistic and fascist regions in certain countries, for nation-building purposes, not least in Sweden actually where I am half from. Therefore, that hides the fact that the peasant is often an immigrant, who had to migrate. Both my great grandfathers in Sweden went to America to work and then came back and bought land in Sweden, but of course didn’t stay in America. The nation state, as a structure, is something that crushes the peasants. I want to form those alliances with what happened with European peasants in the past, and with what is still going on with indigenous people around the world.

CURRENT EXHIBITION

In your current exhibition “The Peasants are Revolting!” The peasant becomes a part of special activities such as fighting or dancing. How do you choose the subjects in your paintings?

The fighting scenes come from a 16th century manual of fighting that was compiled by a corrupt German bureaucrat, and it has got a chapter on fighting with farm tools. I think it was seen at that time as a joke, or as something funny for the posh people who would be reading this manual. But actually, a few decades earlier – in 1524-1525 – there was the German peasant war, where peasants were really having an uprising using farm tools as weapons, but unfortunately it failed – unfortunately in my opinion. So, I took these “Kata”, fighting positions from this manual, and some farm tools I had, to re-enact these positions, to compile drawings for the paintings. I suppose it is maybe a fantasy of preparing for another uprising – you got to practice your fighting skills. The title of the show “The Peasants are Revolting!” came from a protest banner that I saw a couple of years ago in one of the big anti-cuts marches. It is obviously a play of words that “the peasants are disgusting”, as the Norbert Elias idea that they are disgusting for bourgeois people, but also that they are fighting back.

There is something very political in that. How does that idea that “The Peasants are Revolting!” apply to our current times?

That is the question; I definitely don’t have all the answers. I feel like a fundamental area where I have been positioning myself is in relation to the body and materiality, and the self, the subject that is constructed through images. I really want to fight against a self-construction that is really individualistic, that is quite hard, because I think that we are brought up to be incredibly individualistic by all the images that we see around us. The relationship with the materials, like the plants I use for instance, does not view them as a resource for use, but more as a fellow collaborator in the artwork.

In the paintings on view at your current exhibition some peasants harvest pigments or paints. When you collect your pigments or paints, you often dress traditionally, similarly as the peasants in your painting. How do you place this performance in your work?

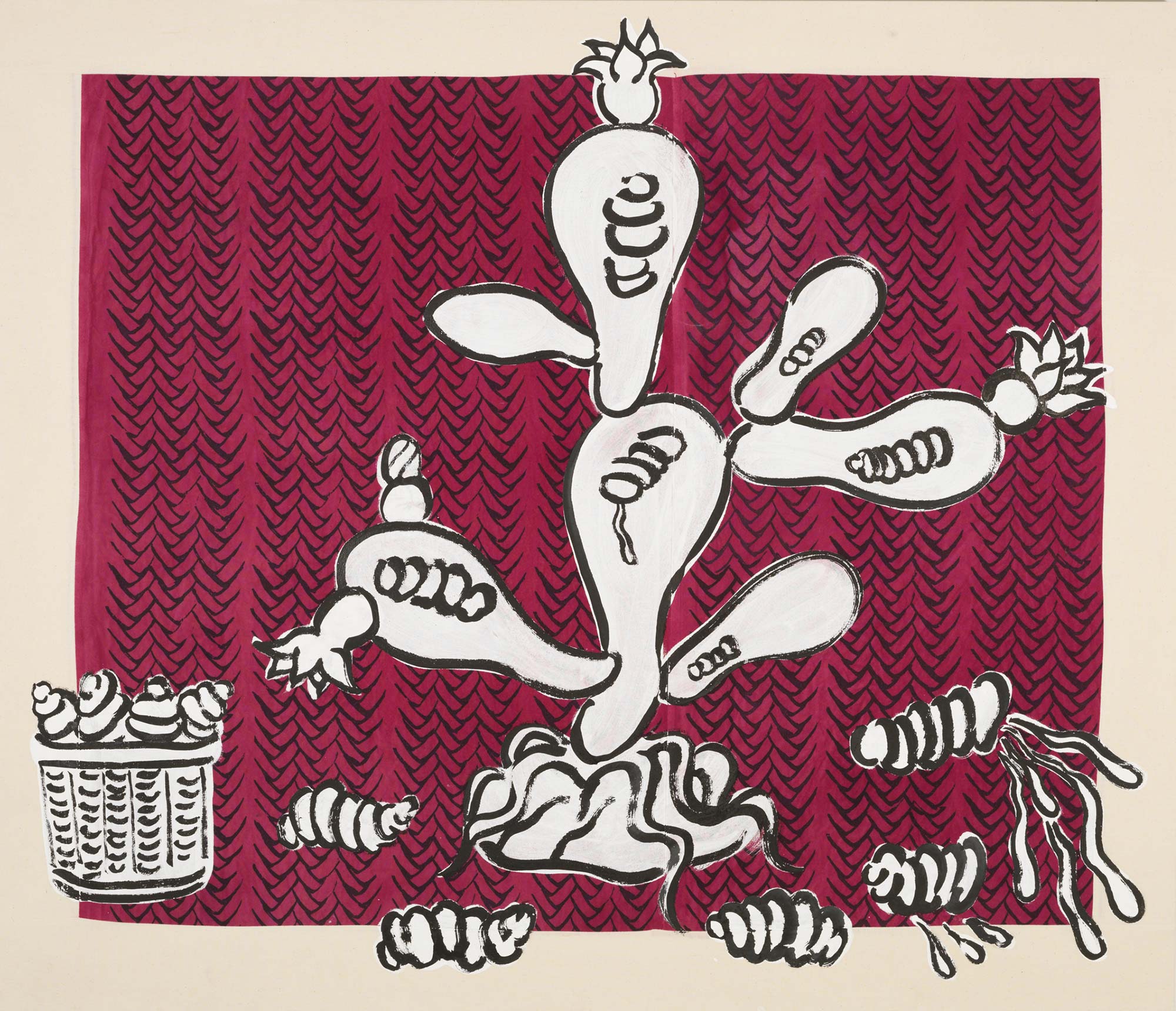

Well I do have moments where I might be making pigments in ‘normal’ clothes. It is a way of bringing it to the public, so I will do it as a performance in front of people. I think that the persona, the dress, or the costume, serve to displace it from the typical educational moment, so that there’s something a bit weird going on, making it not quite a normal lecture on how to make pigments. That is one aspect. Another aspect is that by dressing up, I am actually generating my own imagery for my paintings, so there’s this kind of feedback loop almost where the making of the paintings creates the images of the paintings – not in every painting, but in quite a few. In some of the paintings in this exhibition, it is a combination of myself doing things, but I also I borrowed or stole compositions from the Florentine Codex, which is this 16th century book, titled La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, (The General history of the Things of New Spain). It was written in about 1577, in collaboration with Friar Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan friar, and Twelve Nahua scribes. it is considered the first ethnographic work and it is compiled from various reports and interviews, like ethnographic works would be now. It covers the customs, the history, the religion, and so forth of the Aztecs. It is written bilingually (I would argue trilingually, but I’ll get to that) in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, and in Spanish – but in alphabetised in Nahuatl, because they originally wrote it in pictograms. And then it has all of these illustrations, and that’s what I think the third language is. Anyway, this book has a chapter all about making pigments from plants, and how they named the plants, including Cochineal.

Can you talk more about the use of Cochineal in your work?

The whole body of research for this work comes out of a pigment garden I have been involved in constructing in Almería, Spain, in an organisation called Joya Arte + Ecología. When I was doing the research for the garden, I did not want to use romanticised, ‘native’ plants, I wanted plants that would work in that ecosystem. One thing that I noticed in the lower elevations was that there was a lot of prickly pear cacti infected by cochinilla (or cochineal in English). I found a news report, where people were lamenting it as “the plants are dying”, and these cacti that are “typical of our region” are being harmed, and how the landowners should go out and wash their cacti with soap and water. What they did not mention is that this “typical native of Almeria” cactus actually comes from Mexico, and is a sign of how Spain’s colonialism of the Americas is literally inscribed into the landscape there. What was even more ironic is that all these people were getting upset about this cochinilla infection, when actually it was something Spain earned so much money from importing during the 16th century and in the early colonial period that was second only to silver from the famous silver mines of the Americas. There is actually a manuscript in the British museum called Cochineal Treatise, which is all about the exploitation of cochinilla in Mexico and the silver mines. So it just goes to show how important it was. In fact, Spain maintained a really strict monopoly on the import of cochinilla. What is even more ironic is that cochineal these days is still used. As well as being farmed in the Americas, it is being farmed from the Canary Islands, and the farmers there recently got Denomination De Origen Protegida from the European Union, and I thought: is that to protect it from that ‘fake stuff’ from Mexico?.

You use it as a pigment, how do you do this exactly?

I use process called ‘laking’ to make it a pigment, it is a bit complicated to explain, but it is a way of extracting the colour into water and then fixing onto a solid substrate. It is a cross between cookery and chemistry, fixing it to become a powder that isn’t water soluble, so you can then grind it up and put it to various binders such as egg tempera, oil or painting.

In your painting practise, you re-enact a form of tradition. Within this paradigm, what does it mean to you to be a contemporary artist?

It is interesting you used the word tradition. It is not a word I tend to use, and the reason for that is because I think that it is only modernity that invents tradition, that invents the concept of it. As a word, it has a habit of pushing things into the past, but also to make them static, as if they did not change. Actually, it is interesting that you use that word because it just goes to show how ingrained in modernity we are, ingrained with a conception of linear time and progress. I think you can have change without this being necessarily progress – if that make sense. Nowadays, there are many artists that deal with the past, and in my opinion, dealing with the past is a way of constructing an alternative future. Because by changing what that narrative of history is, what the past is, it actually opens up many possibilities. It is almost as a step you have to do first, to deal with the contemporary.

Why did you choose to illustrate women being part of different activities, which are normally seen as male dominated?

I suppose I want to rewrite history where women are protagonists. I would even contest the idea that all those activities are necessarily male dominated. I think that that is the difference between what becomes famous, what becomes the dominant narrative. For instance, the act of painting, I have done a lot of research into peasants that painted in southwest Sweden, and there were a lot of women painting. They were all peasants, so they did all the farming activities on the side, and also painted. There are many known and named women painters. Also, you can argue that even the more elite-type of painting over the western European art history, there has been plenty of women involved, but not necessarily named. That is often the key. For instance, Peter Brueghel the Elder was supposedly taught by his grandmother to paint. Also, it does come out the fact that I am using my own body, and I am a woman… But it is also that if the figure of the peasant has been oppressed throughout history, the figure of the female peasant even more so. Something that I have been particularly interested in is Silvia Federici’s Book, Caliban and The Witch, which makes an excellent argument for the Great Witch Hunts of Europe as being this genocidal tool used to suppress alternative knowledge’s and alternative practices that were often women-dominated such as midwifery, healing, etc. in order to appropriate women’s bodies and their reproductive capacities, for capitalism. She also links that to what happened through the Americas -very explicitly, to the extent that they exported the notion of witchcraft trials to the Americas, as a way to suppress their religious practices. That is why I also feature paintings of instruments of torture that come from a woodcut, of the instruments of torture that were used in a particular witch trial in Germany.

Why did you choose to represent these particular instruments of torture?

I assume it is weird to paint something that has such negative connotations. I suppose it is just to bring them to visibility. I thing there is a tendency to think of these great witch hunts as just some mad superstitious thing that these people did in the olden days, and not actually as some terrible genocidal event that targeted women, and that should be taken more seriously.

You were inspired by Bruegel’s iconography for your work “Land of Cockaigne”. Why did you choose this reference?

For me, this is a fascinating painting because the Land of Cockaigne means the land of plenty, this peasant fantasy of a place where you don’t have to work and the food just comes up with the knife stuck in it like “eat me”. Actually there is a theory that the word Cockaigne comes from the French word “cocagne” meaning woad ball. Woad is the plant that was used to make indigo in Europe for millennia, and it was actually one of the first big commodity crops in the Middle Ages. It made certain areas that grew woad incredibly rich, specifically Toulouse in France and Thuringia in Germany. So there is the question whether the land of Cockaigne might be a reference to the land where you cultivate woad, so you don’t need to work as hard, because you are rich. Something I noticed quite recently in that particular painting by Bruegel is that off in the right hand corner, there is actually a prickly pear cactus. It looks brown now, but that is because it was painted with verdigris I should think, I don’t know this for certain, but my experience tells me. It would have originally been bright green, but it has gone brown with time, because that is what happens with that pigment in oils. I am just wondering whether he placed this as a reference to the new import of cochineal at that time, to say that the land of plenty is actually in the Americas. So for me it is an interesting reference. And then there is also the idea of not having to work, which I think is great.

24.05.17

Words by Martin Mayorga

Related

Interview

Dale Lewis

Interview