Meet the artist who absorbs memories, and then presents it as a work.

Dale Lewis absorbs memories and emotions, filtering them in the form of paintings. When initiating his artistic career, Lewis’ undertook two or three jobs at the same time, struggling economically and admitting to us stealing paint from his art course. Luckily this paint allowed him to begin making “really big, grubby, and fast paintings”. Inspired by Renaissance painting compositions along with personal experience, Lewis is concerned in representing ordinary moments, violent situations or critiques with a British humorous overtone to “balance” out the mood of the scenes. In the own words of the artist “wherever I arrive in the world, I just absorb and mess around with, and then I present that as a work.”

BACKGROUND

You started your career working as an assistant to Damien Hirst (placing and arranging numerous butterfly wings on his kaleidoscope paintings) and to Raqib Shaw (painting meticulous details in his photorealistic pieces). How did this labour-based practice influence you as an artist? Were you drawn away from their styles/methods?

I think so, because everything was so precise and slow. At the time when I worked for Raqib, I used to paint very small photo-realist paintings that were very smooth and “correct”. I would normally do a small part of a painting, and that could take up all day. Many works took months to finish. I always wanted to make really big, grubby, and fast paintings, so when I left Raqib’s, it was a good opportunity for me to start doing that. At that time, I also had my own studio alongside working for Raqib, where I used to copy photographs in paint, and everything was made quite flat. I normally worked around an hour a day, although I usually felt very tired and ended up doing nothing at all. I think it’s not very productive to work for another artist if you want to be a painter. It was good at the time, and I learnt a lot, but not about my own work. I probably learnt more about the business ‘world’, and the other side of the art on that scale.

How and why did you decide to leave Raqib’s studio?

I actually got fired. That’s the thing when you work for an artist, that the line between what is work and what is friendship sometimes gets very blurry. In a way, we got too close, and I didn’t want to make the work for him anymore. Something wasn’t working. Maybe I needed to start doing work for myself, and he possibly needed that space of not having me around his studio. So, he fired me and afterwards gave me some money, which allowed me to do a painting course at Turps Banana. This course was based near Elephant and Castle, and lasted for nine months, and that’s where everything started.

And how did you find the course? Did you meet somebody interesting?

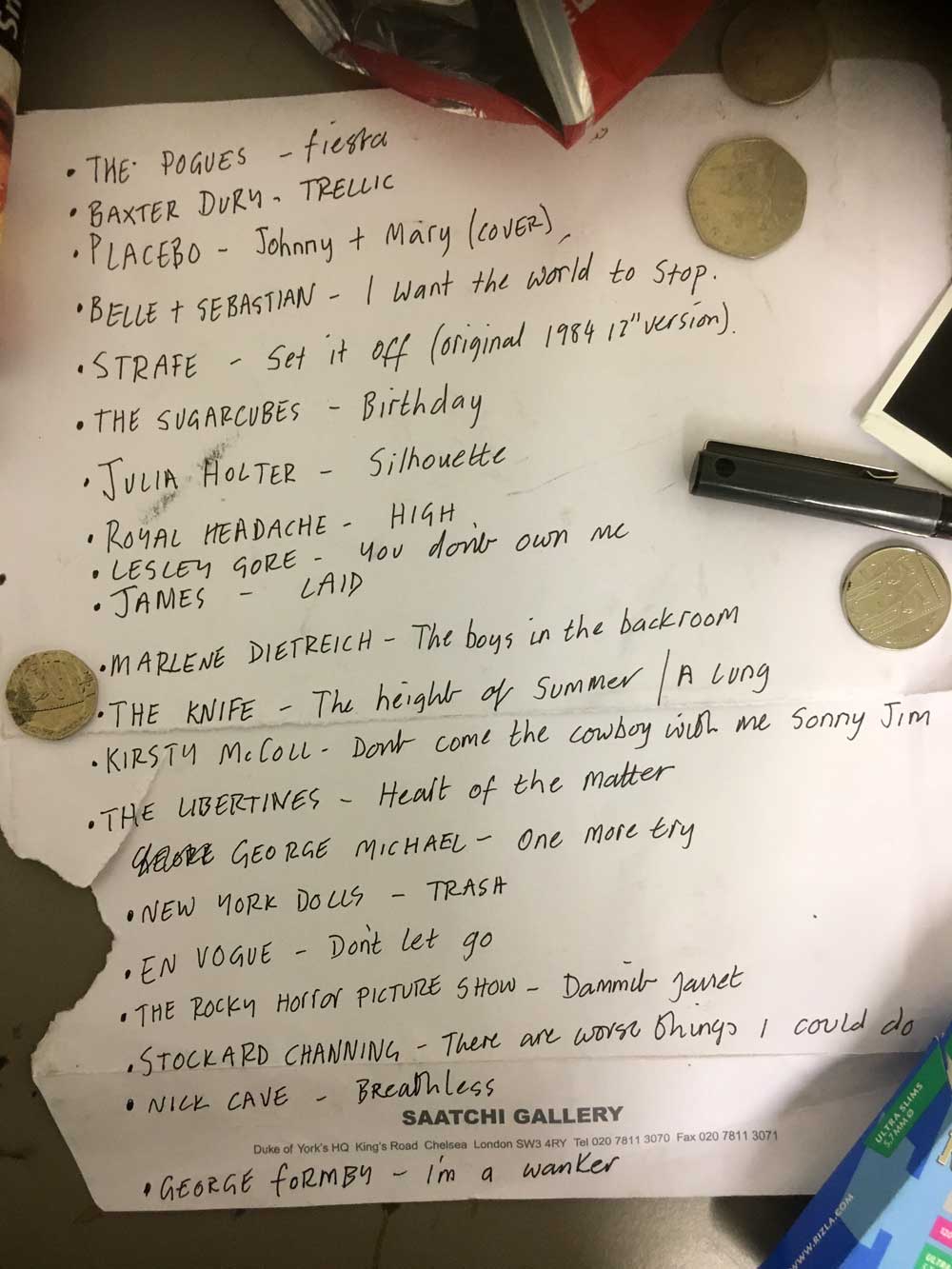

It was brilliant. It was run by Marcus Harvey, who was at the “Sensation” exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. He made “Myra (painting)”, a really iconic work. Marcus set up this art school along with Phil Allen, who currently teaches at the Royal College of Art. They called this school Turps Banana, which initially started as a magazine, and has been running for around ten years now. What is fascinating about this school is that it operates in an alternative way, very much inclined towards a Bauhaus ethos, where it’s based purely in painting and not as much in talking about the work, or thinking about it, but rather actually in the making of the work, and learning though practise. That work ethic was very liberating for me. Then, I started to make paintings in a big size, and at that time I was so broke I had around two to three jobs at the same time. I was working evenings, mornings, and then going to art school, and afterwards I started working for a company that made stretchers for paintings. Somebody had ordered and payed for some stretchers, and decided they didn’t want them, so instead of throwing them, I was lucky enough to take them to my studio. I tried some and struggled with them pretty much the whole time, but then a few good ones started to come out, and two of those works are in the Saatchi Gallery’s current show ‘Iconoclasts’.

A year ago you were chosen to receive the prestigious Jerwood Painting Fellowship. How did it help you?

Actually, I didn’t know much about that Fellowship. I hardly knew it existed because I never usually look at competitions or residencies. To be honest, I just didn’t bother to apply to them because the process of applying was very exhausting, and the competition was too great, so I’d always avoid it. As I was at Turps art school, and everybody applied, I also decided to apply. So, the night before the deadline I thought I’d just write the application. I was actually really drunk while writing it, and when I read it back the following morning I realised it was terrible, but it was also really funny, honest, and direct. I just wrote why I liked painting, what I liked about it, what the Jerwood would do, how the money would help, but in a very short way, not even completing an A4 size. After that, I got an interview, and Phil Allen who was running Turps advised me to bring my one best painting with me to the interview. So I hired a van and a driver with the economic help of this girl I knew at the time, who also had an interview on the same day. We put our money together for the van and when we got there, the office where the interview was held was tiny, so it was quite a task to get this huge painting into the room, and that moment broke the ice. Then, the interview was quite relaxed, everyone was in a good mood, I think there were 5 people interviewing us. We had around half an hour of interview, although it took around 15 minutes to get my work in the room, so it was like ‘Hi, how do you do?’, and then it was over. Following this, I got a call on the next Friday, and was told that I had got a place, and it was the best feeling ever at the time, because as a young artist, I never knew where the money would come from, and what I was going to do at the end of it. It was brilliant to know that I’d got this money to allow me to this point, and at the end of it there was going to be a big show in London with much attention, and I’d also work with amazing people.

Your mentor at that time was Dan Coombs, what’s your relationship with him, and how did he affect your work? What did he teach you?

He’s just been brilliant, and very generous with his time and knowledge. He just keeps feeding me all the best things, and giving me everything I need. He’s so good with nurturing and encouraging. I kind of knew Dan previously, as he had been involved on the Turps course, and to leave the school but still carry on with him, it was just really reassuring. It’s really frightening being an artist, it is for me, I find it terrifying – even still, I find it real scary, because you are always questioning everything, all the time. But for Dan, it felt as he would just hold your hand, and he was with you in this journey. Now, I do it on my own, I’m fine about it, but at the time, I really needed him to guide me. We’d always talk about the compositions, and about what happens with the work, but he was always really supportive, and never tried to make me change what I was doing, but rather to encourage it in the way it needs to go. We still do studio visits, and he came to view the Saatchi show. I always think that all my work, even the one I do now is somehow a collaboration, it’s always going to have Dan’s work somewhere. There’s always going to be Dan’s hand or his thought in my paintings, probably for the rest of my life.

One thing that always strikes me when I look at your paintings are the various references to big names in art history; I love the way you hint at other works as well. Who are your ‘heroes’ in the art world? How have they influenced you?

I usually make sketches on the bus, on a taxi, or somewhere really boring, when I know I have a certain amount of time to do it. In relation to my references, I’ve always loved figurative painting, as I don’t really like abstract paintings or conceptually-based work. So, I have always been attracted to figurative paintings, and the first paintings I used to see before I visited art galleries would be in churches. So, I’d always see some kind of religious narrative as a kid. As I grew up, I knew about Picasso, or saw someone who had a Van Gogh sunflower poster on a wall, and I started seeing them everywhere, so I picked up on those things, copied them, and put them together. I’ve always obviously liked Picasso and Van Gogh because of their narrative and colour, but I’d also like Beryl Cook, who used to paint these very British scenes of women in pubs, but the women are always slightly fat, and they’ve got these weird bodies. Her figures would always be at the beach, at the pub, at the bus stop, or in a café, so they’re really funny, and I used to see them a lot as a kid because my nan and grandad would have little pictures of those around the house. I also enjoy Alice Neel, and Lassnig, and obviously Basquiat. I love the really gay and early Hockney works, along with many more artists. But then, I think that what I’ve managed to do as an artist, because I come from a baggage of 500 or 600 years of painting and cave painting, so that’s why I try to look much further back than the last 50 years for my references, because 50 years of painting is too close for me, and it’s too easy for people to recognise another painter in your paintings if the gap isn’t wide enough, I think. It’s similar to making a cake. I have a bit of Alice Neel, a bit of Hockney, a bit of Basquiat, and then blend it, hopefully well enough, so when I present a work, one reference isn’t more obvious than the other, and you’d only get hints. It’s not upsetting, but it’s really off-putting for an artist when you show a painting and someone says ‘well it looks like Neo Rauch, or it looks like Tal R, or it looks like Guston’, I used to get that all the time earlier on, but I knew I was trying to copy them too much, that’s why I stopped looking at them. I believe when you do find obvious references in a work, it’s as if you haven’t found the right language just yet. As an artist or a painter, you want people to recognise the painting as yours, you don’t want it to remind them of someone else. I also grew up in a sculpture town, and there used to be lots of Henry Moore sculptures. As a child, I remember seeing the well known Henry Moore sculptures with the mum, dad, and the baby. I was always obsessed with Moore, and his use of stretching the figures, or making them really heavy, similarly as my piece “Mayonnaise”, on view at the Saatchi show. His figures are always in my mind, specially his reclining ones, or his family groups. I can’t really stop thinking about those family group sculptures. When I go back to Essex to visit family it’s very common to see teenagers on a bench, or someone feeding a baby, and then I kind of overlay that into a really simple drawing. I always work from memory, never from photographs. This is because I always used to copy photographs, so it’s just horrible doing that for me because there isn’t any life in the painting if you’re just making them as a copy of something else.

CURRENT EXHIBITION

You are one of the groundbreaking young artists included in Saatchi’s new exhibition, ‘Iconoclasts’. How do you think your work fits among the work of other artists in the show? Do you engage in a visual dialogue; are you interested in the same issues?

From the show, I know Daniel Crews Chubb because he was part of the Turps course as well, maybe one or two years before me, so we knew each other from that. In relation to if my works fit with the other works of the show, I don’t know, and I don’t really think about it. I don’t know how important that is. I mean, it does feel very separate because I think if it was a show that was hung, and everything was mixed, then it would be different, but this show feels very unrelated. As if we all have our own exhibition space under the umbrella of a title, and that’s as much as I can say.

Do you have any thoughts on the title, ‘Iconoclasts’? Would you describe yourself as an Iconoclast?

Probably not. I don’t know if there is one. I hadn’t even heard this word before the show. I don’t think people need to read into things too much, or take things too literally, it’s like you interpret it as you will. It has to be called something, so it’s as good as a title as anything else.

Your painting “Eurovision” is one of the selected press images for the show. We’d love to hear more about what it represents and why you chose this specific title! What about the titles of your other paintings such as “Olympians” and Mayonnaise? Is “East Street” a real place?

Yes, East Street is a real street. It’s just a café, but the café is not called East Street, but when I was at my last studio that’s where I used to go for lunch regularly. What it would be very interesting would be to know what you think ‘Eurovision’ is about? If you would have to read it without me telling you this story of what it is actually about, what would you think?

‘Eurovision’ looked as a football game to me, as in the crowd of a football game. I’m originally from Eastern Europe, so In this work, all these people are wearing tracksuits, and this is how a typical Eastern European football game would look like, very violent, passionate, and expressionist, that’s how I saw it.

That’s quite nice to hear. Because some people think there is a mosque in the background, so I didn’t know if they think it’s about recent events, I’ve had that a few times, so I was wondering if that was a general way people looked at it. “Eurovision” is actually very personal. I got very badly beaten up in Brighton, so the building in the back of the work is Brighton Pavilion, quite weird but iconic place. It was the night of the Eurovision song contest, and I went to a pub to watch it. By the time it finished, I was walking home with someone else and we got set up by around 15 people, and we got really badly beaten up. To the point of having to go to hospital. So, this piece was about this night, the night I got beaten up on the day of Eurovision, so every time the Eurovision contest is on, I think of that fight. That’s what my paintings are like, I need to have those kind of feelings or emotions about the people in the painting to be able to paint it, because otherwise I can’t picture or imagine it. Most of my works are regarding something I’ve been directly involved in or seen. I spend a lot of time outside, I walk everywhere, I like to be out late, and I enjoy seeing people really drunk. I like to see people doing all sorts of things in general, so I’m always trying to be out at funny times in the day. I go out and get drunk, but I also go out to coffee places in the afternoon, and that’s a different view. So, for me it’s important to not live this lifestyle, but to have this availableness or open-ness to absorb everything so I can bring it back to my studio and represent it as a painting.

Do you mostly paint strangers?

Yes, mostly strangers or family. The main painting that went over to New York involved a family barbecue scene. I saw someone get arrested at McDonalds car park, so that was a painting, it can be anything, from really personal events such as getting beaten up to just being something I see while having a cigarette on the other side of the road. It could be about people waiting for the bus, or it could be people in the pub just having a drink on a Friday afternoon after work. Sometimes they are very ordinary things, and sometimes they are a bit rarer, involving a personal experience. ‘Mayonnaise’ was from watching a bullfight in Valencia, Spain. I don’t know if it was my memory of it, as I can’t really remember if I made it up or if it was true, but I remember eating some parts of the bull, I think it was the balls or tail, when the bullfight was on. And this meal was served with Spanish Mayonnaise, named Alioli, so I just called the painting ‘Mayonnaise’ for that reason. Sometimes, when the paintings reflect quite horrible scenes, or something quite violent, I like it to have something that’s not to serious, to lighten out the mood. I think there’s lots of humour in my paintings. I want them to be funny, or there’s always that idea of a cute dog or something to balance or offset the negative things. It cant be all violent, or it cant be all very sweet and nice.

Just before I came in, I actually thought that you usually painted directly on canvas, now I see that you have these stretchers whee you paint on and then attach to the canvases.

I usually make the sketch drawings, and then I get water down, acrylic, and then I copy it onto the linen, and then that starts the painting.

In relation to the humour in your paintings, do you use it as a tool to critique, is it just simply observation, or is it a way to balance things out as mentioned previously?

I think humour serves my paintings to balance out, and as in life, you can’t always be miserable, or you can’t always be angry, you have to find something in the middle where you can enjoy everything. You can always find hope in something, in any situation, it can’t all be darkness. I painted a stag party in Brighton, because I used to live there, and it was full of stag parties, which were really quite horrible and trashy, laddy, loud, and violent really, so I called that painting ‘Fruits de Mer’, because I thought it was something so trashy it had to have a classy title to pull it back, and it’s funny. I want people to laugh while observing the painting. If it doesn’t make them laugh, then they’re not really getting round the whole experience. I like it when things are funny, and it gets people talking, it relaxes people. The titles just come naturally. It’s like a British sense of humour as well, because British people can be cutting and dry, and it’s an affectionate way of being with people. It’s not cruel, we like to be kind of nasty, but were not, its just like that.

You showed me earlier in your reference book that you use compositions of classical renaissance paintings. Do you usually go back to one work that inspires you, using it multiple times for your compositions?

Probably it’s “The Feast of the Rosary” by Dürer, that’s one I use again and again. It’s the best composition I’ve found. Mostly anything with hybrids between humans and animals, and some violence. I’ve looked at them enough, so I can kind reconstruct them. I was familiar with using them quite literally, and copying them directly, but now I can take a reference and mix maybe three Renaissance paintings to create one, and then overlay my feelings on that.

That’s what I like about your compositions. I love the way your pieces are so chaotic, and at the same time synchronised, almost with a sense of choreography. Again, it’s all about the balance.

They’ve always got this Classical Renaissance reference; it was a great moment when I realised I could use them. When I was younger, I used to reject Renaissance paintings by saying ‘oh its old, it’s crap’ but now it’s gone the other way, I think it’s the best thing ever, the most important work, and I mostly reject everything that has come after that. For me, using Renaissance references was a good way of holding and gluing my works together. When I didn’t have a good composition, my works fell apart, so if you see a Renaissance painting, it’s almost as an armature. You build a sculpture by building the core, frame, and then you put the substance on top. That’s just what the compositions are like, so if the compositions are strong, I can put you in the painting and all of us in it, and we would all have our place and it would hold together.

You mentioned you lived in Spain for a while, and I believe in some other places as well. Are most of your observations derivative from the British urban scene; and British culture?

On the residency I undertook in New York, most of the paintings I made were about New York, so I referenced some sailors because it was fleet week, and then there was another one of people just crossing the road, because in New York you just constantly wait to cross the road, seeing everyone, and my work was just a reflection on that. I like to paint people on the subway, and I also remember to pass this pregnant homeless woman on my walk from where I was living to my studio, so I used to see her every morning. I ended up making a painting about her and that was my favourite painting. It reflected her, and she had pigeon guardians, and a wrap as a lover, holding her as she was asleep, so it’s kind of this fairytale almost, but it was real. I called that one ‘Morning America’ because I saw her every morning, and also it referred to this idea of waking up, you know, that this is here and something needs to be done about it. Who does that? Whose job is it? I made another painting about Fire Island, it’s the weirdest place I’ve ever been to. There’s plenty of deers walking around, but they’re not shy, so you walk along and then one will start walking next to you. It’s this really trippy, weird place; I made a painting about that. So, wherever I arrive in the world, I just absorb and mess around with, and then I present that as a work.

FUTURE

Can you tell us anything about the future projects that you are working on?

Well, I’m going to go to Miami in December to do the Untitled Art Fair with one of my galleries, and then come back and do a show with Edel Assanti Gallery in London in January. Then, I’m going to Australia for six weeks to visit family and to have a proper break, as I haven’t really been on holiday. I go away a lot, but I don’t ever sit on the beach and read a book, it’s always travelling in relation to work. That’s that, and maybe a residency in June, and then I’ll do a show in Los Angeles in December next year, but I’m going to go there 3 months before to make work, so I think those paintings will be Los Angeles based paintings, rather than London paintings. If I don’t die before then, that’s the plan. It’s good to have a year of knowing what you are doing. I don’t know more than that.

Is there something that you’ve always wanted to do but you’ve never managed to? Do you have any unrealised projects to do with painting?

I don’t think so. I’m so lucky and I’m really grateful for my life, and I really do enjoy it. It couldn’t be any better than this. I mean, I’d like a bigger studio, and tiny things that don’t really matter. I’ve always wanted to command a painting, that’s one of the weirdest things I’d always wanted to do. So, if you were a lifeguard on the beach and you are sitting on the chair, and then if maybe someone could be “blue” and some other person could be “red”, and another person would be “white”. It would act as a performance, where I’ll command the painting, and I’ll try to make the painting through instructions by telling these people how to paint it. I’ve always wanted to do something like that, I don’t know if I ever will. I’d like to make a huge show one day where it spans this giant horizontal length of 50 to 100 paintings, maybe it could be a walk from my flat in London to the other side of London. To paint that kind of journey, I don’t know, maybe something like that, although it’s a bit ambitious.

30.10.17

Words by Victoria Gyuleva

Related

Studio Visit

Dale Lewis

Mix