Finding the individual in a collective history.

Through the artistic inspection of her role models, artist Rosa Johan Uddoh uncovers her own identity in unpacking these “exaggerated versions” of herself. With Uddoh’s research into tokenism and space stemming from her background in architecture and own experiences at university, the artist takes ownership of wider narratives confronting what a black woman should be. The artist comes to grips with her identity through the act of creating, as her story-telling-based practice allows her to reach maximum levels of self-esteem. In fact, it was her winning of the Sarabande Foundation scholarship that granted her the confidence she needed to keep pursuing her artistic ideas. Uddoh’s artworks involve many key influences, such as Moira Stuart, a news presenter who dominated British television with her impartial presence during a time of hostility and fear. Interested in exposing black, instrumentalised identity, the artist also centralises her practice in sport, where she highlights the hyper-visibility of black presence in athletic activity, and its contrasting invisibility in archived history. By considering the parameters that define black identity through the lenses of performance art, deconstruction and casting directly onto skin, the artist roots her artworks in an anthropological and physical state of being. The bodily further underpins Uddoh’s works through her use of nude tones, complementing her interest in how skin colour translates to race.

BACKGROUND

You studied a BA in Architecture at the University of Cambridge before undertaking a Master’s degree at the Slade School of Fine Art here in London. Has your architectural background and in particular it’s linear progression, fed into your practice and thinking?

I’m still really interested in the same things that I was interested in when I was studying architecture, mainly spatial agency, so how we can take ownership of and feel comfortable in space. I think this is partly to do with how spaces are designed, their materiality and how they sit in a wider context, but also about the identity of the person moving through them.

Did you find your time at Cambridge to be affected by white privilege? How did it affect your experience (if at all)?

Yes, Cambridge is full of white privilege, which translates to an environment that is often racist, homophobic and sexist. At Cambridge, I was physically and verbally assaulted, and I also briefly developed a paranoia that I couldn’t go to the library because everyone was looking at me. So here, out of necessity, I began my research into tokenism and space. I wanted to be an architect, but I ended up getting involved in activism.

In 2016, you were chosen for the Sarabande Scholarship by renowned photographer Nick Knight, following your work ‘Thigh House’. How have you found your practice to have developed or changed since receiving this?

I applied for the Sarabande scholarship while I was still working in architecture. Rare for architecture, my boss actually let me go home in the evenings, so it was in this time that I started to make clay casts in my bedroom using air dry clay, which eventually turned into the ‘Thigh House’ project. The Sarabande scholarship has been amazing as they funded my whole masters, and have given me a year free studio on graduating, which I otherwise wouldn’t have had the financial means and so the security and confidence to leave architecture and pursue an artistic practice full time. It’s the kind of long-term funding that needs to happen more in the Arts.

WORK

You focus mainly on representing other people in your practice, but do you believe your own identity to be reflected in the works?

I don’t think I’m really representing other people. Because these characters were presented as role models to me, often at a formative age, they have actually shaped a big part of who I am. E.g. I have a lot of friends who are black British women who grew up watching Serena Williams winning Wimbledon, and who in their own lives have grown up to be the only black woman high up in their fields. So, I’m just performing exaggerated versions of myself, like Serena Williams, in order to unpack that phenomenon.

When I last visited you, you mentioned that you centralise your practice around reaching maximum levels of self-esteem. How does your work help you to achieve this?

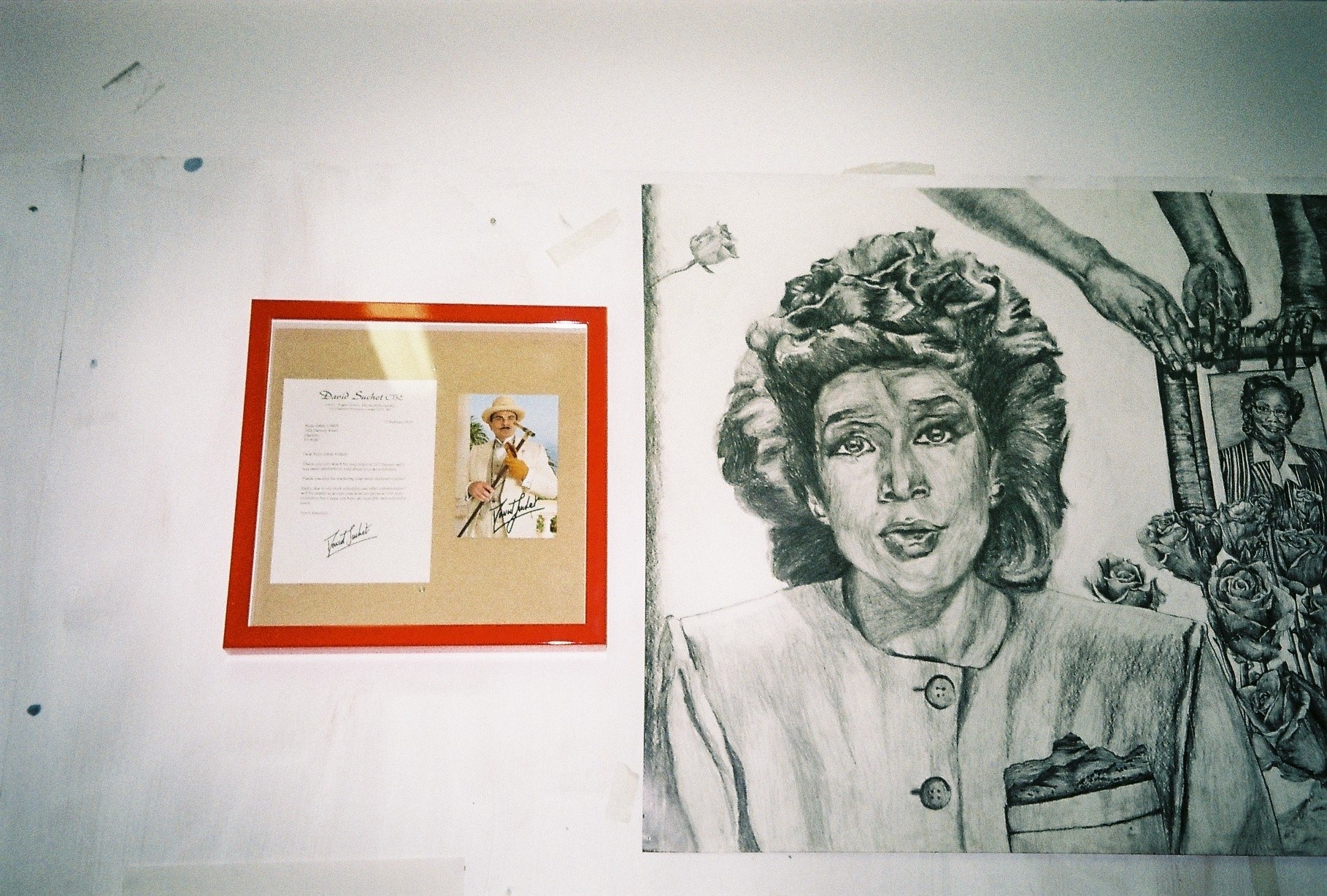

Yes! My aim ‘towards maximum self-esteem’ is a pun on these Architectural polemics from modernist white men like Le Corbusier’s ‘Towards a New Architecture’, mashed together with black feminist activist Audre Lorde’s aims of ‘radical self love’. I often make installations which materially reflect or expose black identity and labour, which I then perform in e.g. ‘Thigh House’ was a tiled roof with each tile cast from a black or brown womxn’s thigh. I also use performance to transform existing spaces into one that works for me, even if only briefly. E.g. I have this project where I sing Alicia Keys solo under colonial-era porticos, which have great acoustics and work to amplify my voice. When I perform, I often perform exaggerated versions of myself that are informed by Black or exoticized characters in popular culture e.g. Meghan Markle, Moira Stuart, Hercule Poirot, Venus Williams, or even my own poo. By working through these characters, I’m able to understand their effect on my own identity better, and take some ownership of wider narratives of what a black woman should be.

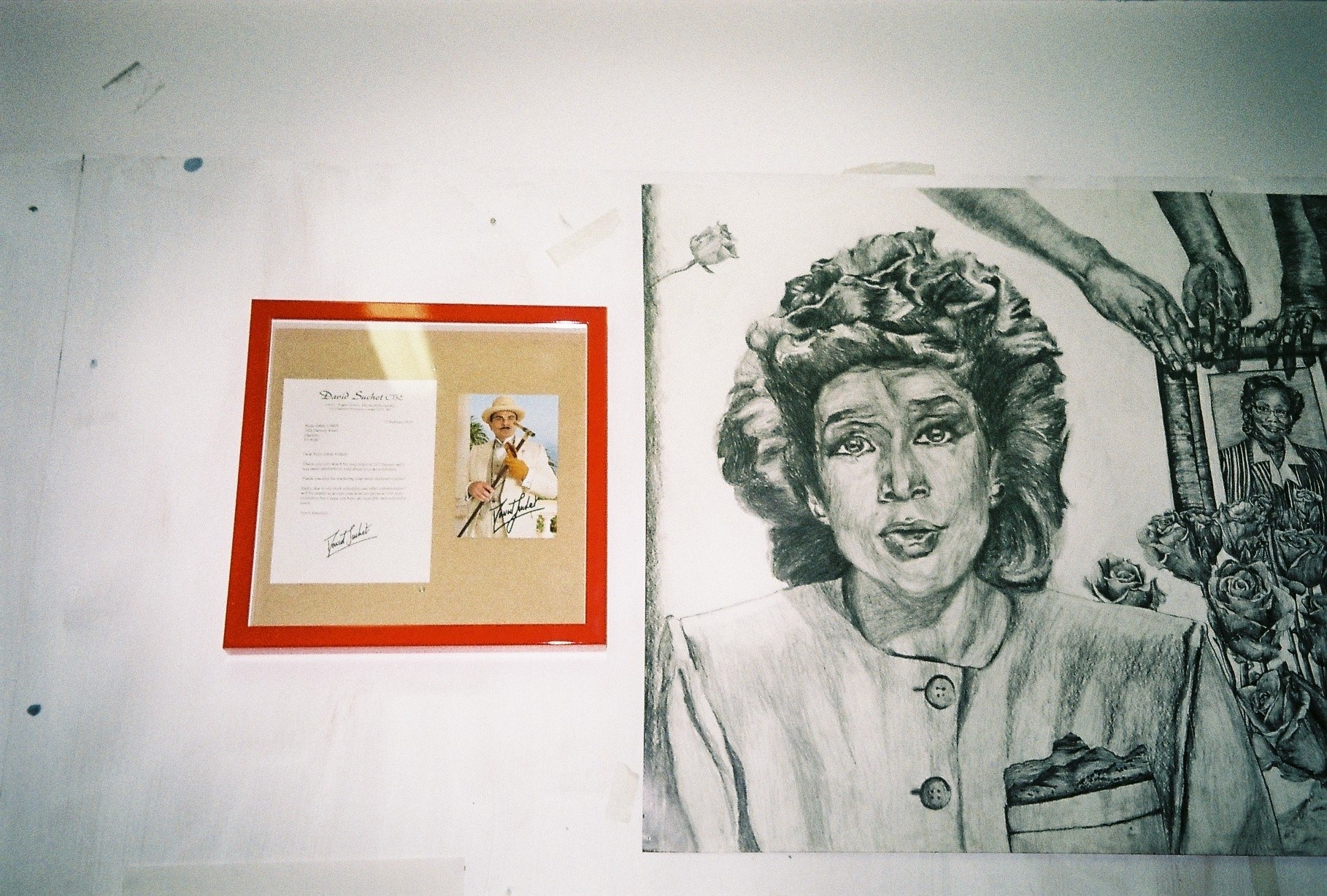

You’ve recently worked on a series of screen prints for a now-past show at Jupiter Woods that focused on British BBC presenter Moira Stuart. Considering her impartiality in these public broadcasts, do ideas of neutrality and omnipresence play into this work and your overall approach?

With Moira, I was particularly interested in her as a black woman who presented as trustworthy, authoritative and impartial, despite appearing on TV just four months after the 1981 Brixton riots and six months after the New Cross massacre, at a time when police and National Front activity was a real threat. I wanted to understand this great feat of convincing performance that she did under very hostile conditions.

It’s interesting how these individual works give the impression of printed editions. Can you tell us more about the play on repetition and ideas of reproduction of motifs, icons and processes embodied in this series?

Through creating these studies, printing Moira’s face over the span of her 30-year performance of impartiality, I began to understand the precision with which she moved her features and angled her face in exactly the same way for every single broadcast. At first glance of all the studies, it looks like the same image, simply repeated like an edition. But when you look closer, you realise each one is unique, and so hopefully appreciate Moira Stuart’s labour in creating each performance of impartiality.

I understand that at the opening night of your show at Jupiter Woods you performed with an analogue autocue, where dancers set your pace and rhythm of speaking through their movements. Are ideas of media regulation and control-at-large a conscious foundation in this piece?

I am interested in complicity around tokenism, whose words are being put in whose mouth, whose identity is being instrumentalised for what gain, and moments when black and mixed-race women have been used as a symbol of the British nation. You saw this with Una Marson, the first black producer at the BBC, who made the first programme on the BBC Empire service broadcast to the black West Indian population, during WW2. Then later with Moira Stuart, as the first black woman to present news, and more recently with Meghan Markle as the royal family’s delegate to commonwealth meetings.

You teach a course on sport and art at the Liverpool John Moores University. Can you tell us about your focus in this, and in particular the notion of hyper-visibility vs. invisibility?

I am interested in black history and performance, but this often means I am met with silence in the archive, as these histories were not considered important in the West to document, save, file properly or record. So, it’s difficult to find a genealogy of black performance artists, or documentation of black British everyday life. On the other hand, sport is an arena where black people are over-represented. Moreover, sport grew hand in hand with photo and film innovations designed to capture sporting bodies live, at high speed and in high quality. This means sport is a rare field where you can easily access an excess of images of black performance, simply through Google, without having to go to an archive. Because of this excess, it seems important to me that to understand black performance in white spaces, you have to look inter disciplinarily at sport as well as art and everyday life. Rightly or wrongly, sport as well as musical performance defines a lot of the parameters of black identity.

Do you find performance art to be the most powerful medium of communication for your work involving sport because it is inherently about activity and movement?

Yes, I think so! Sport and art performance are both about the body. Being black means performing constantly, and it’s clear through looking at black history that survival is sometimes an athletic feat.

Works such as ‘Thigh House’ involved creating a roof out of tiles which were casted on a diversity of thighs, or ‘Who We Are As A Couple’ where you recreated and deconstructed body parts of Meghan Markle. Would you say that body politics plays a key role in your works?

Yes. Audre Lorde’s Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as power, has really shaped my approach in using my body and the bodily in my work.

Many of your works are presented in skin-like colours, from across the spectrum of tones. Is this a conscious decision?

It’s something I hadn’t really thought about until our chat, but yes, I guess – I’m interested in skin colour literally, as well as how it translates to race.

FUTURE

You have already encountered many forms of communication in your artworks, from screen printing to performance art, but do you feel that you’ll be trying new media for your ideas in the future?

Yes, I try to find the best medium to fit the idea or character I’m trying to communicate. I think that comes from architecture.

23.08.19

Words by Martin Mayorga

Related

Studio Visit

Rosa-Johan Uddoh

Interview