Dreaming of a dreamworld.

The work of London based artist Kora Moya Rojo depicts a dreamworld inhabited by aquatic organisms, blobby shapes and hybrid creatures. With her ceramics, drawings, and paintings, she pays homage to her coastal hometown, Cartagena. Having come to realise how significant the sea is to her, a constant longing for the freedom it offers is palpable in her vibrant renderings of fish and water. These symbols, which are associated with birth, fertility and sexuality, underpin her research into alternative ways to cope with social constraints such as the pressure on women to become mothers at a certain age or the controls imposed over their bodies through history. Rather than portraying gender-specific figures, Moya Rojo creates universal representations that embrace a wide variety of identities. Humans and non-humans are constantly at play, whether it’s plump lips that look like sea creatures, close-up ears that resemble splashing waves, or cats that are reminiscent of cabbages. As well as transforming animals and food into fictional characters, she plays with the idea of integrating organic and mechanical features in her everyday items like chairs and beds. Similar to the fruits and plants she paints, her colour palette is composed of bright colours including blues, greens and reds to evoke optimism. As a versatile creator, Moya Rojo is open to integrating a variety of formats in her practice. She is particularly excited about developing installation pieces, experimenting with 3D mediums, and even considering combining art and gastronomy one day. Whatever form her production takes, she aims to envision a post-human utopia that encourages viewers to embrace their fantasy selves and discover faraway wonders.

BACKGROUND

What has been more influential to your practice from growing up in Cartagena, Spain: its archaeological sites, fertile farmlands, modernist buildings, regional produce, or religious traditions? Can you recall any anecdotes in relation to any of these that have struck you the most?

I’d say all the ones listed above have influenced my work in one way or another. When growing up, I remember saying that I wanted to be an archaeologist. I used to cycle my bike around the mountains of Portmán trying to find “treasures”, but by that I meant quartz crystals. These minerals can be sited in old mine tailings, and Portmán was a natural harbour at the service of this industry, so there were plenty near the pits. I have this recollection stuck in my head that I will never forget; and it was the moment I found a half-buried quartz stone near the cane fields. I was amazed by its size; it was so big! I rushed back to my grandad’s home and picked up a shovel and dug it out. I still have it at my parents’ house.

Spending childhood with your grandfather in Portmán, did the ecological disaster from the dumped mining waste in this bay fuel your fascination with rendering mutated aquatic organisms and representing the dreamworlds that lie outside of the horizon?

Absolutely! When I first cracked on with my new body of work, I became very absorbed in the toxicity that was present in La Bahía de Portmán. I still recall the contrast between the pit black sand and the neon yellowy orange from the remaining sulphur that covered the soil across the beach. In fact, in my painting ‘Black Sand’, the sand is orange because of it. When I was younger, my mum would buzz about how this bay looked when she was a kid; it went hundreds of metres back, making it one of the most wonderful places on the Mediterranean Coast.

Has being surrounded by the sea in both Spain, your country of origin, and England, your current residence, made you develop a stronger affinity with fish and water? Are the associations tied to these, like birth, courage, and femininity, central themes you address?

The older I get, the more I realise how significant the sea has become to me. I was so accustomed to being surrounded by it before I moved to London that I entirely took it for granted, so I really cherish it when I go back to visit my family. This longing is translating into my paintings, especially after seeing all the connotations behind it, being related to those notions you stated (birth, courage, and femininity). I just love the sensation I get when I look into the horizon and I see nothing but the immensity of the ocean and the sky. I find freedom there.

WORK

Female hysteria was a medically-diagnosed female malfunction you first discovered in Paula Rego’s exhibition at the Tate Britain. Can you guide us through your depiction of the bizarre practises performed to treat it in your own ”Hysteria I-III” series? Although these three works respond to historical control over women, do they also speak of today’s dominance over our own bodies and health?

When I began working on this series, I focused on studying the practises that they performed on women to “cure” them from the “wandering womb” disease. The one that really grabbed my eye was the one called “scent therapy”, which was the standard cure for “hysterical suffocation”. Essentially, good smells were placed under a woman’s genitals and bad odours at the nose, while sneezing could also be induced to drive the uterus back to its “correct place”. After reading about this, it also made me think about how contraceptive methods are mainly designed for women’s bodies, neglecting men. There’s been research that proves that for the past 50 years, there have been few changes in male contraception compared with the range of options available to women. I realised that, even though these two matters are very different from each other and that are well apart in time, there are several similarities to date that lead to wanting to impose control over the female body and the choices that women make.

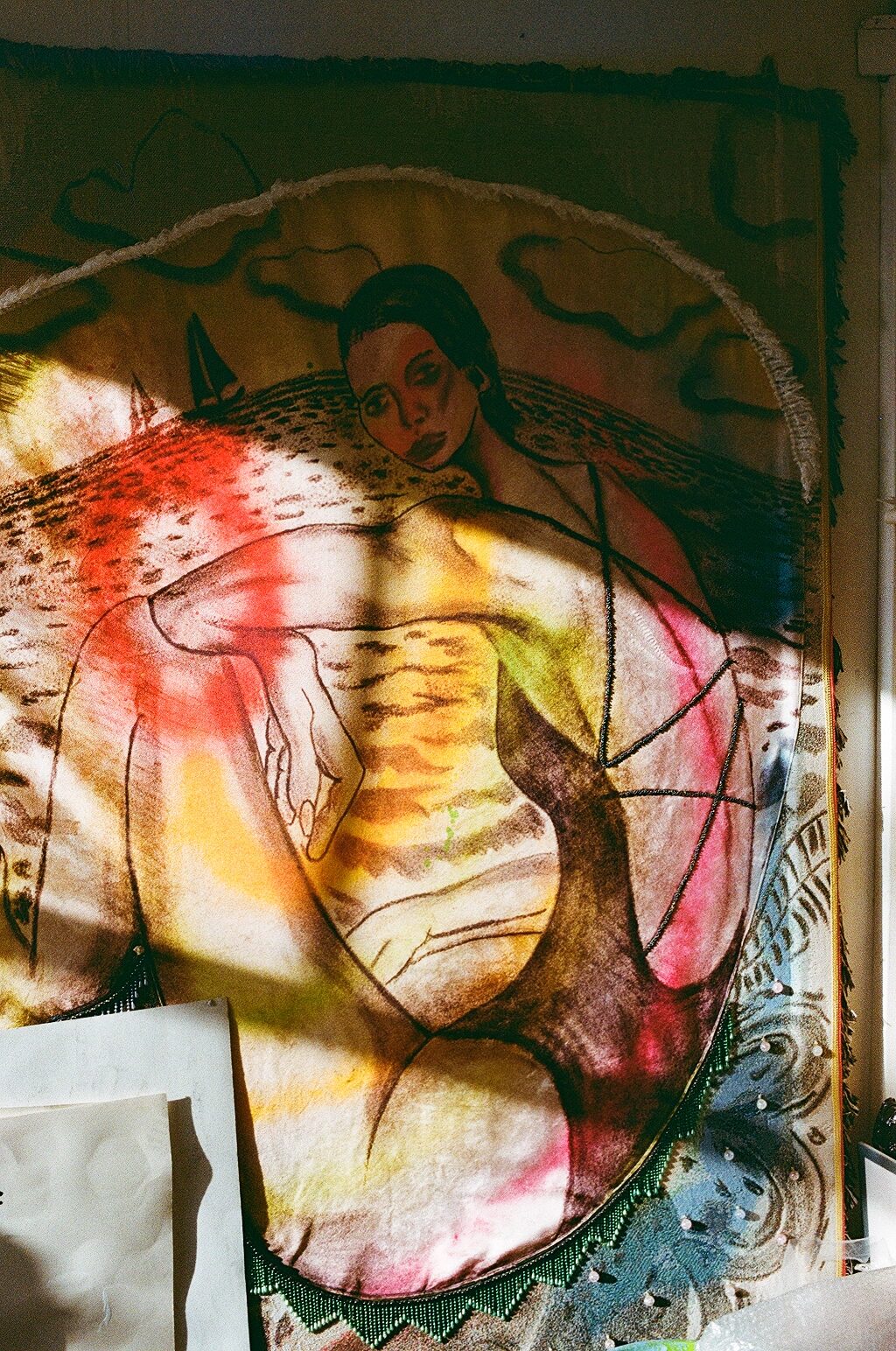

At your North London workspace, the lounge is dedicated to your works in progress, the hallway contains your recently finalised series, and the bedroom stores your older pieces. Do you distribute your production in differentiated spaces in order not to be contaminated by your previous approach? By not having your completed canvases visibly around, are you avoiding a forced cohesion among them?

Whenever I embark on painting a new piece, I take it as a fresh start. If I worked in the middle of finished or old pieces, I’d unconsciously compare them to each other and the final result would be affected. Since I’ve been wrapped up in this body of work for a long period now, I feel like the same style comes out naturally and I don’t have the need of placing the other pieces within reach to reassure me that there’s cohesion among them.

There I also spotted a mood board with cut-outs of artworks, flowers, and fruits. What draws you in from the oval geometry diffused all over these diverse references? Evoking reproductive organs and planetary orbits all at once, are you interested in this shape’s capacity to lay out a wide spectrum of scales? Is creating blobby and bulbous bodies a way of reclaiming more fluid identities?

I’ve continually been drawn to blobby shapes; there’s something very satisfying in how these flow and merge with their surroundings. There’s a sereneness and calmness to them. A lot of the shapes that I subconsciously create in my paintings seem to evoke reproductive organs, probably because a lot of the objects that are found in nature also look very similar; some fruits, for example. That said, the fluidity of the forms takes me to a place where identity isn’t really important. I just want to create characters that everyone can identify with.

Since stumbling on the Adobe Fresco app during lockdown, sketching with it has become essential. Does having the option to experiment with colours, layers, and outlines in a digital medium that’s not yet definitive for you yet push your practice into new directions that a tangible material wouldn’t allow?

Working digitally allows me to trial and error with colours and techniques pretty much instantly without really wasting materials in case things don’t go as planned. When I used to draw with ink or pencils in my sketchbook, I sometimes deemed it quite limiting since I couldn’t change things up straight away. However, I allow myself to experiment in a non-digital approach every now and then, particularly when I want to try new materials, like modelling paste or spray paint.

Some of the transitions you’ve undertaken have included merging the backgrounds and foregrounds of your layers, externalising the eyes of your figures, or painting straight from the ground without an easel. How come what was once fixed is now flexible, floaty, and fuzzy?

At first, when I commenced this body of work, my focus was set on the individual elements of the paintings. I somehow treated these canvases as if they were a collage by collecting memory cut-outs and pasting them together on the canvas surface. However, gradually, I started noticing this urge to tell stories about subjects that I find intriguing or based on my direct experiences.

All along the pandemic, your paintings evolved from a predominantly obscure palette of blacks, greys and purples to your go-to radiant blues, greens and reds. Was this colour incorporation a reaction to counteract the darkness of the period?

That’s actually very interesting and I didn’t think about it in that way, but it makes absolute sense. During the pandemic, I was trying to disconnect from reality as much as I could, so taking a 180-degree turn sounded like the most suitable plan. It also seemed like it was the best occasion to play and to start over. Back then, I wasn’t really taking my art practice as seriously as I do now. Deep down, I knew I craved making art for a living and wanted to be an artist, but there was something that I was missing that wasn’t allowing me to fully focus on it. I guess the extreme situation we were all going through made me reconsider what really mattered to me and finally decide to go for it.

The internal chair and the external hand are motives that have persisted throughout your various series; the former is indicative of comfort and stability, while the latter is invasive and uninvited. Given one possesses what the other lacks, are you keen on exposing moments of tension?

I’ve recently started adding recurring motifs to my paintings. It happened by coincidence, but now I do it intentionally. I believe it helps to create a common link between the different pieces and adds a familiar layer to the story that I’m trying to tell in every painting. As you said earlier, with the hand I’m trying to render an intrusive figure. I like that mystery of not really knowing what it is or where it’s coming from.

Would you say your larger paintings illustrate detailed sceneries and therefore require closer inspection, while your smaller ones portray close ups and thus can be seen from further standpoints? You move with ease amid formats, but in which one do you paint more confidently, and why?

That’s totally accurate. When I paint on a larger scale, I tend to place emphasis on the scenery while conceiving the piece as a whole. However, when it comes to smaller ones, I centre my attention on the details, portraying a specific element as the main character. I’ve always felt more comfortable painting larger pieces. I find it easier for some reason. A year ago, I decided to challenge myself and paint one small painting a day for a whole month. I aimed to overcome the fear I had towards compact surfaces, and by doing that I forced myself to learn how to paint on miniature formats again. It definitely was a stimulating and useful exercise, but I don’t think I’d do it again! Haha.

Refraining from the passive roles in which women have traditionally been cast, why do you opt to explore the female condition in your paintings without adding in any gender identifiers?

I think that gender is such an abstract concept and not everybody feels the same about it, so for me it was critical to create a figure that represented all of us. The main goal when I developed these genderless characters was to offer a sense of liberation to the viewer. At the end of the day, we’re all human beings in our own unique means, and that’s what really matters.

Writer and cultural theorist Astrida Neimanis mentions in her book ‘Bodies of Water’ (2017) that “for us humans, the flow and flush of waters sustain our own bodies, but also connect them to other bodies, to other worlds beyond our human selves” (p.2). Submerging characters under marine terrains, are you venturing towards the combination of the alien and the familiar, as well as the human and the post-human?

I’ve persistently remained fascinated by the sea, even though I’m not a good swimmer and I would typically hate going to the beach when I was younger. However, there’s something very mysterious and magical about it. It’s like if it was a completely different world compared to what we’re familiar with, like you said, alien. I guess the fact that there’s so much that we don’t know about it keeps me wondering and coming back to it.

Taking an analogue camera with you everywhere you go, is the photography documentation of your day-to-day completely separated from your pictorial technique, or are they both interrelated in their recollections of memories?

It definitely sprang up as a hobby but eventually, I came to the conclusion that one of the reasons why I was so into this type of photography was the nostalgia it gave me, as well as creating new memories. One thing that I enjoy doing when I go back to my parents’ is looking through old photo albums and analysing the pictures that my dad used to take. There’s something about taking a photo and not being able to see what it looks like until the roll gets developed. Waiting for anything seems so out of the ordinary nowadays, mainly considering that we live in a fast-paced lifestyle where things happen instantly. Doing so, I feel that memories and photographs are properly appreciated and enjoyed.

Does your meticulous cleanliness and organisation in the studio extend to other areas within your process, from drafting social media posts in advance of posting to digitally sketching in preparation for painting? What spontaneous alterations are you open to integrating over the length and breadth of your practice?

I consider myself quite methodical when working. I do like to plan my social media posts in advance and also curate the look of my main page. At the end of the day, social media is another tool that artists can utilise to showcase their work; it’s like an online portfolio. When it comes to sketching digitally, I tend to carry out the same routine, which usually consists in researching a subject or tracing over shapes that excite me until a composition emerges. Even though my creative process often follows defined steps, I’m always open to trying new things and getting out of my comfort zone.

Initiated by a bizarre dream, “The Hive” stages a vaginal-looking ear with four enormous bees revolving around it. As if it were an undesirable, ripened fruit, does the piece deal with women’s freewill (or lack thereof) over their own fertility and sexuality?

Based on my personal background and observing today’s society, I took notice of how the female body is seen as a reproductive machine. Some women become mothers due to a certain pressure, which is derived from social norms. All of these are usually accompanied by unsolicited advice and comments from other people, sometimes even strangers. Not to even mention the burden that women who can’t have children undergo because they’re infertile. People should be welcome to do what they please with their bodies, and no one should judge or persuade anyone based on the decisions they make.

Do you map out the mythologies and symbologies embedded in your paintings beforehand, or are they revealed to you after bringing the works to fruition and observing them as a whole?

It happens both ways, but normally I come up with an idea that involves visual elements, and then I look up the symbolism linked to it. To my surprise, they habitually relate to the topics that I’m interested in, like it happened with “The Hive”. In that painting, I referenced a dream in which bees, water and fish appeared. After investigating these symbols, I discovered that they were all connected in the same vein, which was the conception of fertility.

FUTURE

While in residence at Joya AiR in Almeria, Spain, you created three ceramics in natural clay extracted from the surroundings. Having brought the hybrid creatures from your sketches to sculptural form for the first time, would you consider joining your 2D and 3D pieces into an installation anytime soon? What about mashing-up various canvases to craft diptychs, following your latest ‘Ruins’ painting?

Definitely. I’m very enthusiastic about expanding my practice towards the three-dimensional field. Making ceramics that accompany my paintings is the next step I’d like to take. I imagine the objects from my paintings coming out of the canvas and turning into 3D tangible objects. I can’t wait to jump into that project!

Another residency at Art House Pani, Tequisquiapan, Mexico is on your calendar this year. Will you keep your focus on moulding with natural resources such as wood, wicker or rattan from the region? Considering the shipping downsides when returning from abroad, would drawings be an alternative option?

I’m in love with Mexico and its culture. The architecture, the vibrant colours everywhere you look, the food, the craft, the folklore. It’s just pure inspiration. I can already tell that the paintings that I’ll create throughout my residency are going to be very vibrant! I’m very much looking forward to living that journey. Works on paper will definitely be one option. I’m also considering painting on canvas and then sending them unstretched back to the UK. Maybe it’ll be a good opportunity to also test and paint on different surfaces, like objects I find in the course of my stay there.

Almonds, lemons and kiwis are edibles you’ve given attention to in your compositions. Can you envision yourself using food as a vital ingredient besides acrylic and oil? Would you test out the blending of art and gastronomy someday?

This idea has been buzzing in my mind for the past few months. I’m still wondering how to properly approach it, but I will definitely do something that combines art and gastronomy in the future. I believe that cooking and painting have a lot of things in common. Paints act as ingredients; merging the colours in the mixing palette is the equivalent of chopping and combining the ingredients, and painting on the canvas parallels the process of cooking. I love seeing how a combination of ingredients transform into delicious meals after the process of preparing them. The same happens with painting.

04.03.2022

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Kora Moya Rojo

Interview