The performance of the everyday.

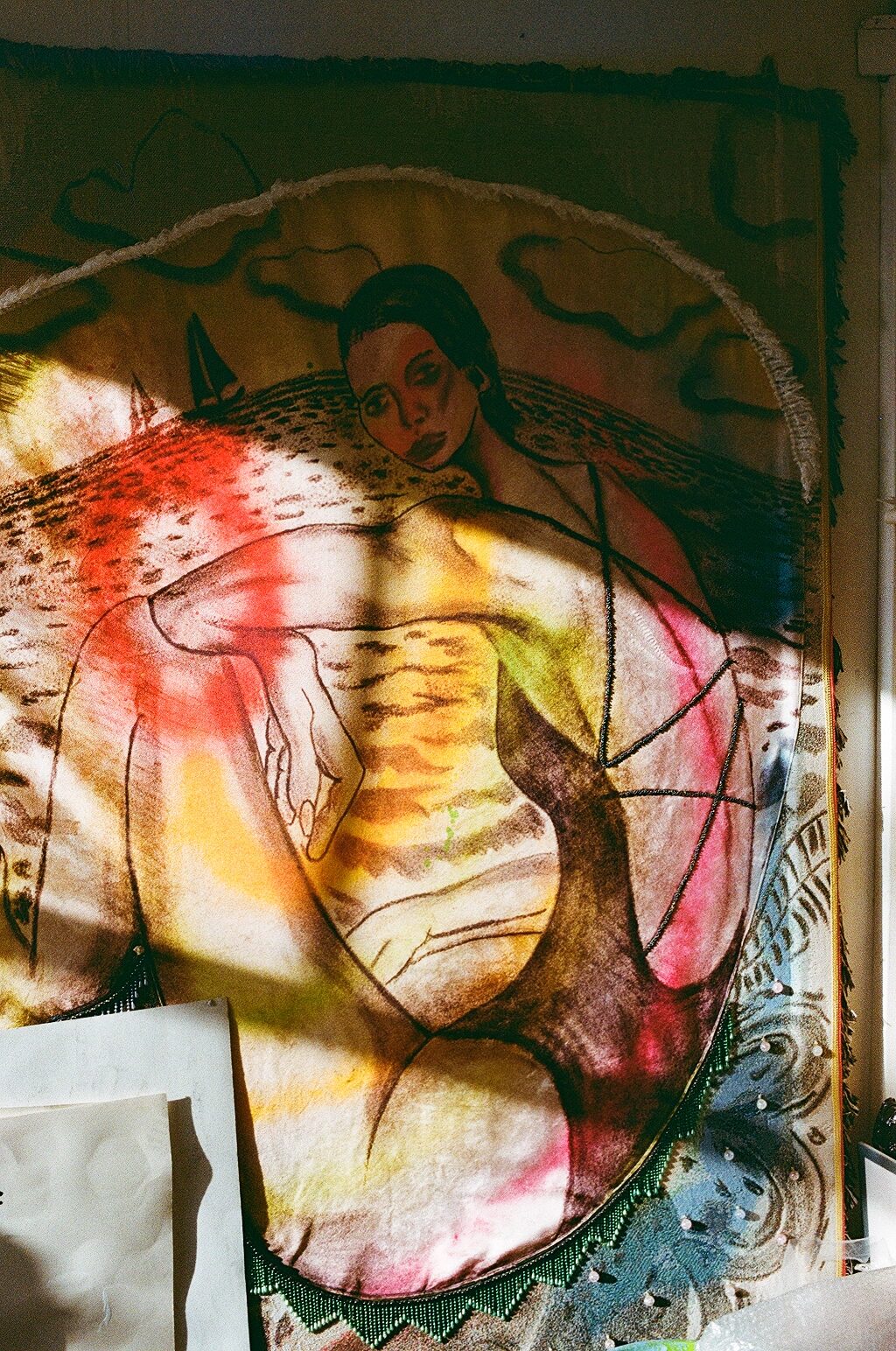

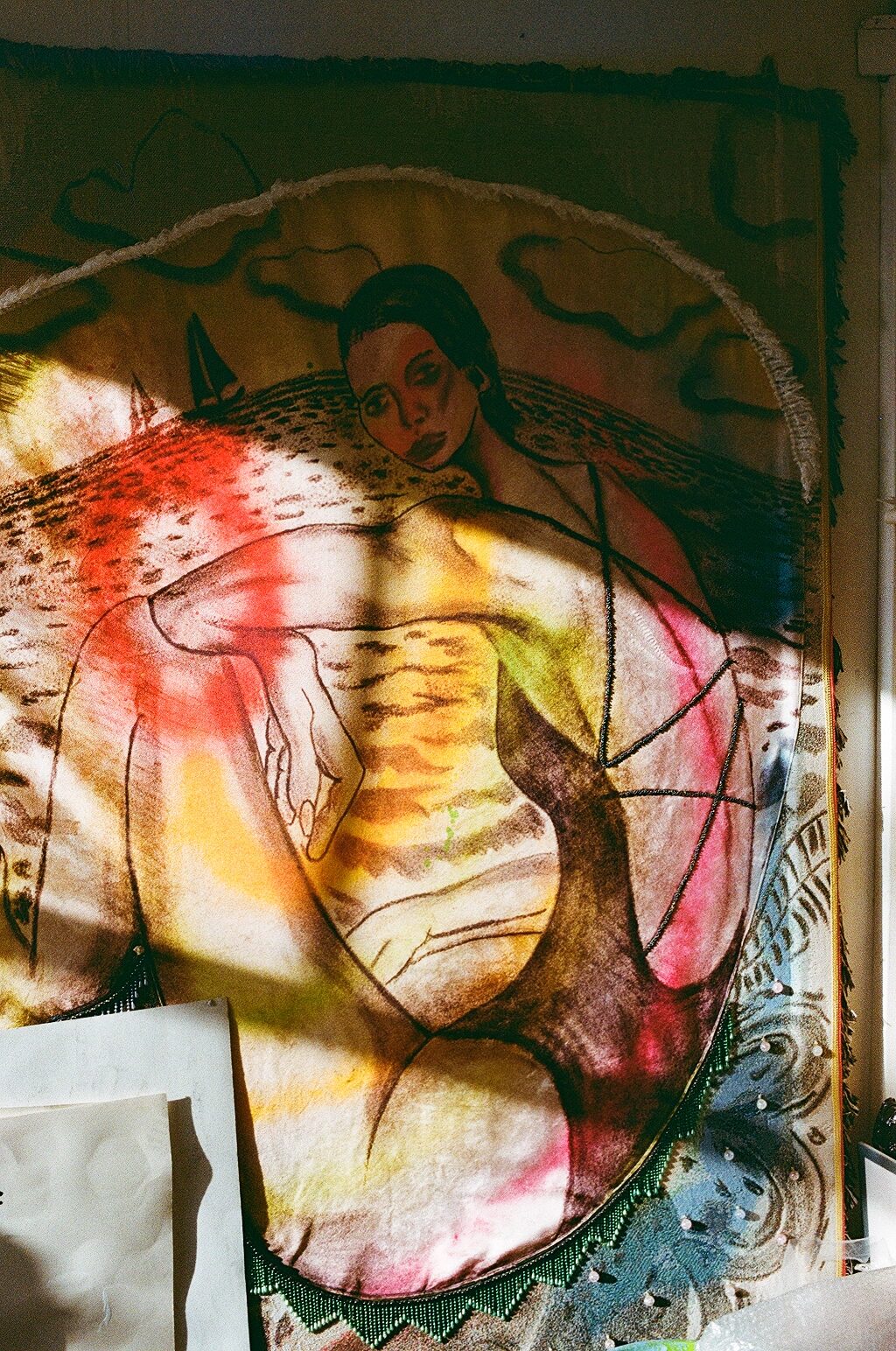

Expansive, technical and varied, artist Christabel MacGreevy is a polymath in the truest sense of the word. Due to a camera malfunction, I ended up visiting Christabel’s studio twice. I found myself looking forward to being in her magnetic presence; partly due to her erudite nature, but also because she takes a genuine interest in whoever she’s in conversation with, often turning a question back to me. The multiplicity of human nature seems to be at the core of her work and reference: folk art, mythology, the British Museum as a vast repository of cultural history and ‘craft’ that revolve around collectivity. The first time I visited, Christabel was working on a series of painted ceramics. She has since finished a residency at Ceramica Suro in Mexico where she has further honed her skills. When I returned a few weeks later, the topography of the studio had completely evolved, as she was now turning to a commission of bespoke chandeliers “with amorphous ‘blobby’ curves”. During both visits, propped against the wall were life-size quilts that she had been working on throughout the pandemic. The stereotypically ‘feminine’ craft had forced her to slow down and connect with a well of archetypal womanly power that stretches back across centuries. A natural extrovert, Christabel uses her practice as a means of fostering community and in doing so, turns the preconceived idea of artists toiling away in isolation on its head. She learned some of her quilting skills from a “group of hilarious older women” and volunteered for the initiative Fine Cell Work which is a charity that rehabilitates prisoners through paid needlework training. Christabel is currently working towards a solo exhibition that will focus upon textiles, ceramics and sculptural pieces. Materiality and tactility emerge to the forefront.

BACKGROUND

Having studied an undergraduate degree in Fine Art at Central St Martins, and progressing to a diploma from the Royal Drawing School, how has your cross-disciplinary practice evolved alongside the institutions you have been part of?

When I attended Saint Martins, I had many friends undertaking product design, graphics, jewellery, and fashion, as well as my classmates in Fine Art doing painting, film, sculpture, performance and installation. I was intrigued by all these different disciplines and never saw Fine Art as limiting in what I could make. The artists I find most interesting bridge various forms of media. Simultaneously to my studies there, the cultural convergence between art and fashion was becoming the norm (e.g. brand collaborations with artists and the way magazines started to operate). Sometimes the medium is the message and the point, and so by changing mediums you can emphasise very specific things. In contrast, The Royal Drawing School was an amazing opportunity to specialise in just drawing for a whole year. It was a great discipline to draw for up to eight hours, five days a week and to be able to stay focused. Even though I don’t meditate, it has gotten me closer to that state of concentration and allowing one’s subconscious to take the lead.

Your grandmother Anthea Craigmyle was also a painter in her lifetime, how has coming from a lineage of female artists informed your transition into painting?

People say, “you can’t be what you can’t see”. In that way, I feel very blessed to have had artists, particularly female artists, around me when I was growing up. Because of this, I could see that it was a viable career path, and a reality that could be mine too. Watching my grandma, Anthea Craigmyle, painting every day right up to the last year of her life was an example of determination and discipline, which I think is key to a fruitful studio practice.

Your degree show centred around textile pieces, and you have also had professional ventures in fashion with the company you co-founded, Itchy Scratchy Patchy. What does this practice – which has roots in traditional feminine craft – encapsulate for you?

There is something about subverting things that are traditionally ‘feminine’ into symbols of power that I really appreciate, for example Judy Chicago’s 1970’s Feminist work ‘The Dinner Party’. This is not a new idea, but it still has resonance and meaning to me as a woman and an artist. I find it interesting that I was drawn to make textile pieces with embroidery for my degree show, and then set up a clothing brand with a focus on embroidery and embellishment later on. Subsequently after closing the brand, I returned to using textiles to make quilts as art pieces. It seems that in one way or another, I want to be working with cloth and stitching. Perhaps I am not yet fully aware of what attracts me to it but it is consistent with my creativity.

WORK

Multi-disciplinary in nature, your practice has driven you to fabricate ceramics, painting and quilts. Where do you find commonality among these varied modes of object-making?

The commonality is my taste, the colour palettes, the drawings that I make, and the shapes that I come back to. I particularly enjoy shapes with amorphous, ‘blobby’ curves. Within my sculpture practice my work is more abstract, the shapes are reminiscent of bodies and nature. I am not sure why we always relate curved shapes to ourselves or to the natural world, is it due to our own self-obsession? Or is it because the world is built upon a shared logic of shape and form? I am currently expanding upon these in clay during my residency at Ceramica Suro in Guadalajara, Mexico. Working in the third dimension, I think less and work more instinctually. I embrace it as a way of working through the subconscious and my half-realised thoughts, then using the conclusions gained from that process as starting points for drawings.

Recurrently featuring intimate love scenes, and having based your series of drawings for ‘The Cedar House’ at Golborne Gallery on the possessions of your late grandmother, how much of your work is an expression of private moments that otherwise go unseen?

Ultimately, the subject matter centers myself or aspects from my own life. However, through the intimacy of these private moments I am seeking the commonalities of human existence. This is why I often return to drawing still lifes, I enjoy its lineage within an art historical tradition, and that it is a way of capturing an era, either through signs of the times (e.g. logos, branding). I repeatedly come back to bathrooms and kitchens with my still lifes due to the very intimacy of these locations, and the way we choose to arrange them being so intensely unique and personal. They are private spaces that most people we know will never see. I also see the sink as somewhat of an anthropomorphised human form. It is a big ‘gluggy’ hole, where things disappear down and are washed away. Simultaneously soothing and sexual, the watering point is an emblem of the mother, the centre of the home. Both clean and dirty, it is these very contradictions that make up a person in their entirety. In my drawings for ‘The Cedar House’, over sixty works on paper portraying inanimate objects build up a very personal portrait-in-absence of their late owner. Her character and her taste emanate through these objects that she amassed over a lifetime. The objects we choose to surround us in our homes are indicative of the life we lead as well as the life we desire. They set the scene of our everyday performance. In some ways, clothes perform in a similar fashion. Through garments and objects we build a persona and subsequently, an identity. These things are fundamental to our individualism and to our sense of self.

Your most recent solo show drew from the novel ‘Orlando” by Virginia Woolf, which comments on gender fluidity and the expectations that come with masculine and feminine roles. What are you communicating by integrating the play between sexuality and identity as prominent themes in your work?

I’ve always been very aware of the performance of gender long before I had the language to express my discontent with it. When I was a child, I insisted on having a boy’s hair cut and asked everyone to call me Chris. I could sense the differing expectations for boys and girls in the way that teachers interacted with us at school. I remember being furious about being a girl. As a woman now, I am interested in the strong reaction I exhibited to the categorisation of gender as a child. If gender is truly a construct then we should defy all of its societal obligations. We should play with it, subvert it and enjoy doing so.

Citing folk art as a visual reference for your practice, what do you find engrossing about outsider art that you do not with mainstream aesthetics?

Outsider art and artefacts haven’t been placed within a canon or tradition in the way that ‘recognised’ artists work is. I love the way there is no officialised reading on an object: it is open and unknown, allowing for a multiplicity of readings and stories. I love the innate magic and curiosity of these drawings, objects or buildings. They fill me with an awe towards the person who made them. They are completely oblivious to the audience, their pursuit of creativity being for no other reason than a burning compulsion to create. One of my aspirations this year is to visit the ‘Palais Ideale’ in the South of France, a pebble and concrete construction by a French postman built over three decades, who often worked at night with an oil lamp. Why he wanted to build it remains unknown, but it is mad and wonderful and I am so glad that he did. I need to see it for myself in the flesh.

Extending an anthropological repartee by deploying mythological symbols, which stories have appealed to you and subsequently been incorporated into your depictions?

The story of Kronos, Ouranos and Zeus I find alluringly violent. As Creation Myths go, the fury intrinsic to Greek myths seem to parallel the apoplectic force of the Big Bang. Unwittingly, from a time thousands of years before Physics gave us the Big Bang Theory, great force and pressure was understood to have brought the world into being. Kronos castrated his father and sent his foaming testicles into a raging ocean, from which Aphrodite was formed. Ouranos cursed Kronos and exclaimed that his own son would be his downfall. In a vouch to safeguard himself, he ate all of his children whole at their birth. However, his wife finally grew sick of this, and tricked him by placing a large stone in blankets while keeping her youngest hidden away. Zeus grew up and came to overthrow his cruel father Kronos. There is an amazing moment in the story where Kronos is poisoned and begins to vomit out his insides. Zeus’s siblings are expelled in order of being eaten, followed finally by the stone. This exact image was repurposed on a patchwork quilt I made when I was looking at the notion of archetypes and what they share in common with narrative tradition.

Engaging in research trips to The British Museum (in the run up) for your exhibitions, you investigated charms, icons and talismans associated with fertility. How do you interpret this learning facilitated by these establishments that house historical and cultural artefacts?

I am obsessed with the British Museum and the treasure that is contained within those walls. Pre-covid, I have never seen it less than packed. My fantasy is to have permission to draw there before it opens at 10am and have all the rooms to myself. The breadth of world history that is possible to observe just by moving from room to room gives indication to the billions of individual stories that make up the history of mankind. It translates the enormity of history into something tangible and individual; a tiny comb owned by a woman in the Roman era, fertility charms from Ancient Abyssinia, tiny gods and goddesses for home shrines. The curiosities are infinite. This is not an intellectual understanding of history, but rather an emotional one, understood through shared experiences across a time span of multiple millennia. My favourite suite of rooms contain the Greek pots. The idea of story telling through fables is something I love, and the way these pots weave reality through events of the time, incorporating fantasy and myth is bewitching.

FUTURE

Speaking of a forthcoming show that is still in development, and your mindfulness not to rush the process, what elements of the works have been established and what aspects are yet to be decided?

I am currently working on a series of patchwork quilts. They are exciting to make but quite labour intensive and slow. Life under the lockdowns over the past year has been quite helpful in making me less impatient and accepting that things take as long as they have to. I am also working on sculptural elements that work alongside them, but that is still in its early stages. I developed a new sculpture technique last year with jesmonite to create a series of hanging sculptures, like chandeliers. I have recently been obsessed with the possibilities of clay and its tactile nature in your hands. It is likely that both of these materials will be present in some form.

Earlier this year, you shared that you had participated in a quilting class with a group of older women, which resulted in a series of textiles. Can we anticipate further works where you engage in collective actions with communities?

There is an interesting tradition of patchwork as a communal activity, for example, the community of Gees Bend where quilting was passed down the female line within families. Another example that is directly communal is the Aids Memorial Quilt. This was a community quilt conceived in the 80s to commemorate all who had died of Aids. Weighing around 54 tons, it remains the largest piece of community folk art in the world to this day. In that sense, it is fitting that I learnt to quilt from a group of hilarious older women. A few years ago I got involved with Fine Cell Work. It is a charity that runs rehabilitation projects in prisons by training prisoners in paid, skilled needlework to make tapestries and embroideries. I visited a women’s group at HSP Send in Surrey when I was helping raise funds via a charity auction. I saw firsthand how much needlework had fostered their self-esteem during the long hours spent in their cells. I would love to work with them in the future.

09.06.2021

Words by Charlie Siddick

Related

Studio Visit

Christabel MacGreevy

Studio Visit