Examining authorship and authenticity in today’s saturated world.

In age of ubiquitous mobile and computer devices, drones, and social media invading our daily life, that the artist Charley Peters is one of those fascinated by the topic is no wonder. Many of her artworks revolve back and forth between reality, illusion, physicality, and the virtual. Her precise and labor-based works are balanced out by quick and intuitive gestures, and her latest works only “exists” virtually on Instagram. We spoke to the artist about not having to justify her works intellectually, the two lives of a painting, and her upcoming works.

BACKGROUND

You recently completed a PhD in Art Theory. How and why did you break through, from devoting yourself to explaining your works in lectures and conferences, to your current urge of just making?

I completed my PhD in 2006, it had an element of practice but my focus was mostly on writing, I felt closer to what I was reading and thinking at that time than what I was making. I value arts education very highly, but I also now acknowledge that academic institutions can be an artificial and restrictive environment for artists if they spend too much time there. I realised quickly that I didn’t like going to conferences, I hated speaking formally to large audiences and I was bored by most of it…I knew I wasn’t meant to think like this but over a two-day conference I’d hear one or two interesting papers that would excite me and make me want to make work but the rest would be dull as shit and make me feel tired and irritated. Researching a subject to PhD level is an intellectual privilege but over a sustained period of time – my PhD took 6 years as I was teaching at a university part-time – that amount of overthinking and questioning led to dissatisfaction in what I was making. The more I knew, the more I started to become aware of what I didn’t want. I’ve always had an internal struggle between logical thought and intuition, I enjoyed writing about art and constructing arguments through text but it’s a different process to making in the studio; more cerebral and illustrative, whereas making work comes from somewhere that’s harder to articulate. Now I think the work I’m the most enthused about making comes from a less conscious position, somewhere almost otherworldly that I can only access when I stop thinking analytically. It’s taken me a long time to stop ‘thinking’ and feeling the need to explain my work. After my PhD I didn’t make anything for around three years. I felt like I needed to go away and purge myself of overthinking. I moved to London, got a full-time job in a museum, hated it, and when I thought I was going to burst of frustration I felt the urge to return to making work. When I started again it was with the most basic elements – black line on white paper. It meant nothing other than what it was and this felt liberating and positive. Doing a PhD helped me to be a better writer but I felt like my work was much less rich for having to justify it intellectually. I’m sure for other artists it might work out better, but the PhD version of me was riddled with frustration and discontent.

You were part of the Griffin Gallery Residency Programme during February-March 2018, in which you collaborated with a number of artists by making works that only existed virtually. Can you develop this idea? What other limitations did you explore during this residency?

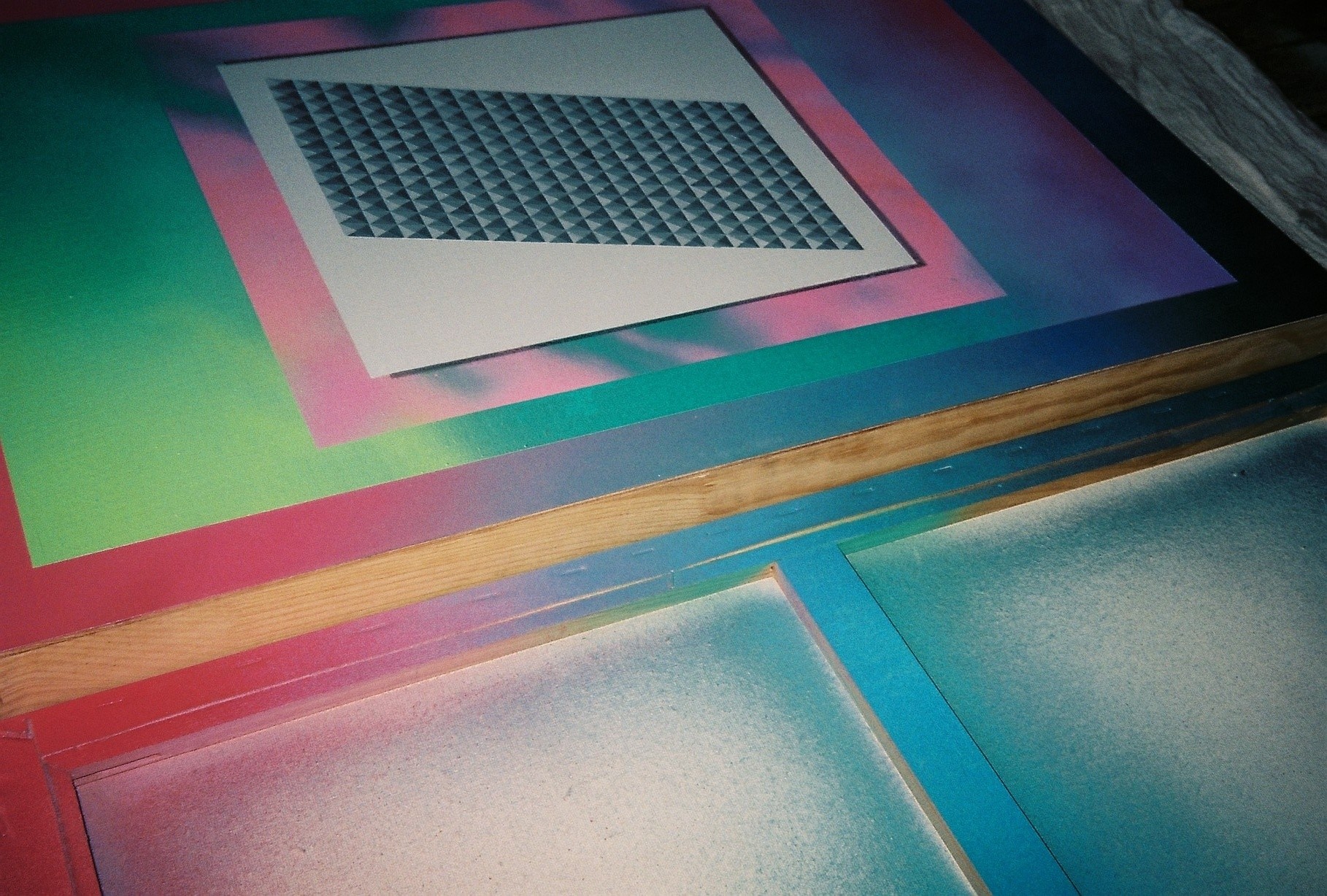

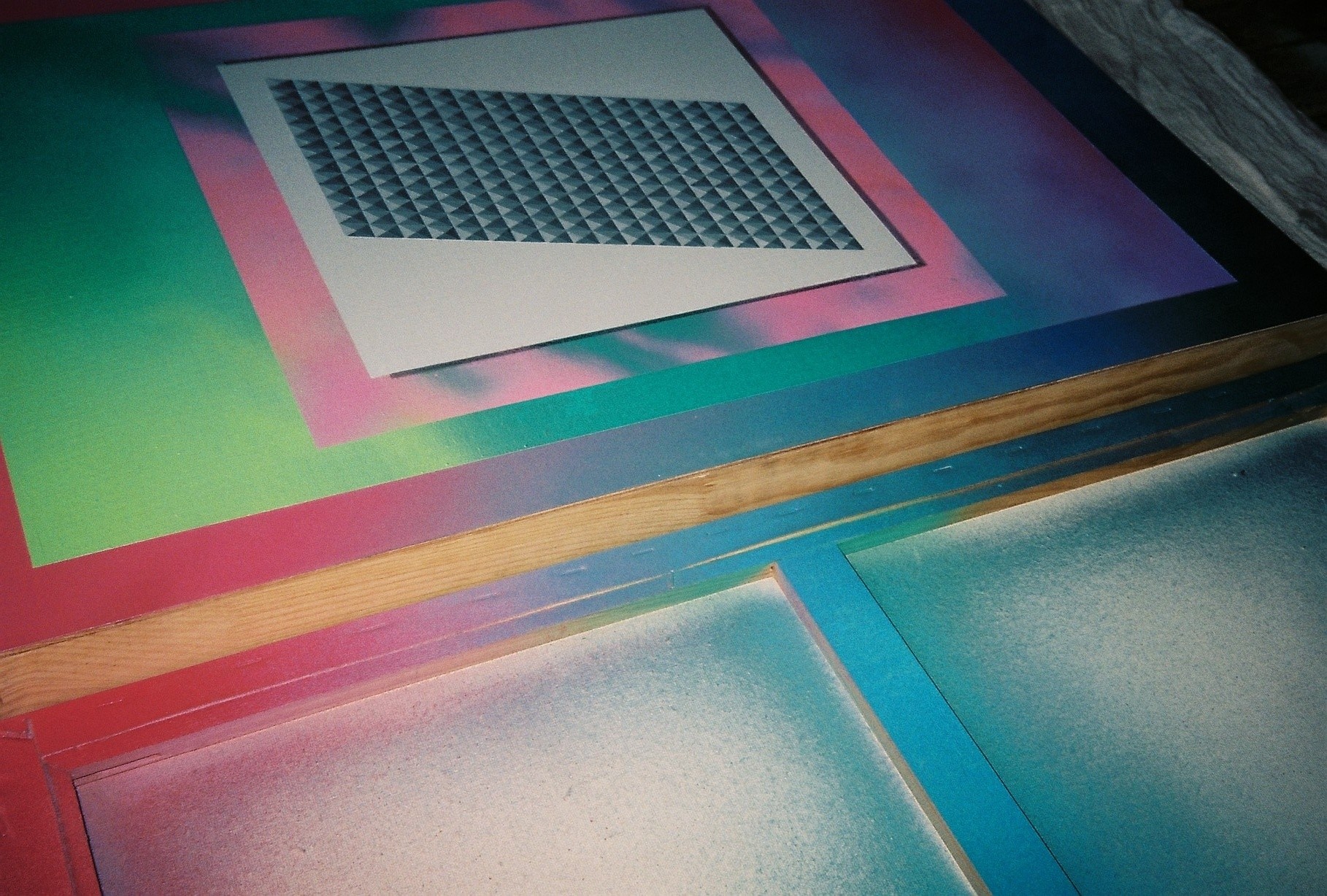

This was a great experience for me. Over a month in the residency studio at Griffin Gallery I worked with seven different artists: Fiona Grady, James Petrucci, Remi Rough, Tash Kahn, Frederic Anderson, Charlie Lang and Sean Roy Parker. I never collaborate with other artists so this was an equally challenging and enriching process. The work we made during each collaboration evolved organically over the time we were in the studio together. I asked each artist to consider bringing along something that was a signature of their practice, for example, Fiona brought some vinyl, James a UV light and Sean some found detritus. Besides that, we could only use the materials provided by Griffin Gallery so mostly we had a lack of control over what we were using to make work. We had to work together to negotiate the frustrations of paint and surfaces we wouldn’t normally use. These limitations were very freeing and allowed us to improvise in the studio – using paint in different ways, deconstructing surfaces etc. We worked with a palette of only red, green and blue (the colours of the screen) and each day we would make 20-30 artworks very quickly by responding to what was in the studio, photographing them and then deconstructing or discarding them. The only place the works now ‘exist’ in actuality is on Instagram. I’m very interested in the materiality and posterity of painting in the digital age and notions of authorship and authenticity in a world saturated with images. The residency allowed me to explore this while seeing how other artists work. Collaborating necessitates having to let go of methodologies that may be habitual to you and to reassess what is important about what you do in the studio yourself, while embracing new ways of working. It’s not easy to let go of what you know but I think it’s important to question why you do things the way you do in order to move forward. At the same time as making work together, we had great conversations about art and life and in most cases have developed ideas to extend our collaborations beyond the residency.

How would you describe your working process? Do you use any digital tools?

I don’t use digital tools to make work, I find it so difficult and slow to make anything if I can’t just use my hands. These days I start paintings intuitively by laying down fields of colour and then I think about how to divide up compositional space and add areas of visual focus. I work in successive layers that become progressively more refined. I don’t plan paintings in advance, I do have sketchbooks full of half-considered ideas but they aren’t studies for finished paintings, just quick gestures that might feed into something once I’ve started a piece of work, but just as easily might not. I work on several paintings at once which stops me fussing too much over one painting. In between each layer of a painting I draw quick sketches; they are in some ways helpful to stave off the worry of not knowing what I’m doing next but in other ways useless as they are so unresolved – loose lines scrawled on scraps of paper from unfocused visions in my head. I do spend a lot of time looking at the work I’m making in the studio before adding the next layer of paint. I use spray paint to lay down colour and mark out physical space quickly and without too much thought, and acrylic with a brush to add information to smaller, slowly painted, masked off areas. I add structure, or paint over areas of the composition to calm things down and achieve some kind of visual balance, I hate my work getting too fiddly and conscious. Although I don’t use digital media in my paintings I do like ‘remixing’ my work digitally using apps on my phone. I’m interesting in how paintings that are born from a material, embodied experience in the studio can be reconfigured virtually, so I do make digital sketches of things…mostly animations of paintings I have stored on my camera roll. These are useful experiments in how the digital can interrupt and/or expand on the physical experience of painting. Not sure they are actual ‘things’ yet though.

WORK

I am struck by your belief in the two lives of a painting. Can you explain this idea further?

This relates to your last question in a way. Whereas I don’t use digital tools to make my paintings, I can’t imagine my work existing without an online presence. For me paintings do have two lives; the small backlit jpeg on a screen that thousands of people see on Instagram and the physical, sometimes imperfect painted object with a physical surface that fewer people see on a gallery wall. I think it’s important to acknowledge this. More people see my work online than in reality and I like that there are surprises when people who have seen my work on Instagram see it for real in a gallery. I love painting for its ability to make magic – it is an illusionary process and can trick you into seeing spatial depth, optical movement, complexity, perfection and light that’s not really there. Because I don’t plan my paintings and work responsively, I adjust compositions by painting over elements as I reconsider the work while developing it. When you see my paintings in reality you can see the areas I’ve painted out – because I use tape and mix acrylic paint with a heavy body you can see the build up of paint against the edges of the tape in the layers of work I’ve painted over; these are like ‘scars’ on the painting’s surface that you can only see in reality but not often in a photograph. On screen my work may appear as ‘images’ but in the flesh they are definitely ‘paintings’ that have nuances of gesture, proportion and physical surface that doesn’t translate onto a screen. Paintings of 1.5m look the same size as paintings of 20cm on Instagram but in reality the experience of the shifts in scale, space and the sensuality of paint application are very different. So yes, for me paintings have two lives; a life as an ‘image’ online and a life as a ‘surface’ in physical terms.

Your works emphasise in compositional elements such as line, space, colour, shape, light, texture, etc. Does this make you a formalist?

If that means my paintings don’t ‘mean’ or ‘represent’ anything or aren’t discussed in emotional terms then yes, I’d be happy with being a formalist. Although, of course, I don’t really like being defined…

Speaking about definitions! Given suggestions of being a “post-digital” artist, or a “geometric” artist, amongst other frequent terms used to describe your practice, do you consider yourself as a painter, concerned only in painting?

In so much as my work is driven by my engagement in painting – it wouldn’t exist without the act of painting, but it would exist without its classification by genre. I don’t consider myself a ‘geometric’ artist because I’m not especially interested in geometry per se, but moreover use simple shapes to control space on the painting’s surface and because, to me, they have a perceived meaninglessness – they don’t literally represent anything in the real world. I also find definitions such as ‘geometric art’ limiting and dated; there’s a lot of ‘geometric art’ being shown today that could have been made any time between 1960 and now, and I find the lack of challenge in what that means frustrating. I think my work is abstract as it is non-representational and I am engaged more than anything with the relationship between painting and the formal elements of covering a surface; colour, form, composition etc. I love hard edged painting, minimalism and abstract expressionism but I don’t think we should be making new work that looks like a pastiche of work made 40 or 50 years ago. I wouldn’t want to put myself in a sympathetic or nostalgic position. I’d like to make work that looks like it’s of today, the Internet exists and it undoubtedly shapes how we see, experience and remember the image. This is relevant to how I make my work and how it exists in the world, but I’m still suspicious of labels such as post-analogue/post-digital etc. They will be as nostalgic in a few years’ time as ‘geometric art’ is today.

Why is the colour temperature of your work shifting its mood to a moody/subdued and possibly a more serious palette?

I think that again, I react against definition. Until recently my palette has been fairly high key, I like the purity of strong colour and how it feels full of light and space. But recently I’ve been using darker tones and I’m interested in how these are working. They probably do feel more serious and for now I’m happy with that. I don’t feel settled yet, I still have lots to explore in terms of colour and tone. I don’t want people to think they know my work so easily and I don’t want to know it either. I wouldn’t like to be the ‘bright colour artist’ any more than I’d want to be the ‘post digital geometric artist’. I remain hungry to explore new things with every new painting and to reserve the right to also reject them if that feels like the right thing to do. I’m hard on myself – nothing is ever quite right or good enough – but I think that’s a good thing. Maybe.

Pairs of opposites are manifested in your practice – from hot/cold, movement/static, dark/light, to crammed/loose, and even two different speeds, from an intuitive speed to a very controlled and geometrical one. Can you explain further your interest in these dualities?

I’m not sure…I think they are probably formal considerations of what makes something interesting for me or adds tension and/or balance to a painting. I do tend to favour even numbers, divisions of two or four. Perhaps this all has a deeper meaning than I’m aware of but mostly I think I make decisions visually; I don’t want to make an ugly mess any more than I want to make something over-considered and boring. I do enjoy the temporal qualities of painting. It can take me weeks to finish something and the process is usually a combination of quick, intuitive painting and more laboured, precise work. The tighter areas of painting allow me to slow down – it can be a frustrating process but it gives me time to think. In these elements of the paintings there is a logic at play that in many ways I hate but I also think it’s important as a means of controlling too many spontaneous impulses and to add structure to formlessness. But conversely I’ll often spend days painting something very rigorous and precise and then paint over part of it with a fast, gestural mark. Again, I think maybe this is a reaction against something…the length of time something takes to make, notions of perfection, counteracting something logical and easy to understand with something that feels distinctly different, the sensual pleasure of destroying something beautiful…I don’t really know and I’m not sure I need to work it out. I do think though, that the act of making a mark that could potentially ruin something I’ve spent a long time on, does seem to finish it off nicely.

You have recently exhibited in two shows at Griffin Gallery. What can you say about your works on view at both “Do Re Mi Fa So La Te” curated by Karen David and “1 Godley VC House” curated by Tim A Shaw, Emma Smale and Niamh White?

The work in “Do Re Mi Fa So La Te” was something that I made in the studio and was selected for the show by Karen. It’s a group show that uses the musical score as a metaphor for the use of colour in painting. I think the work of mine in the show is a good example of what we were just discussing, where there is an intricately painted area offset against a hurried gestural spray that was applied at the last minute. The work for “1 Godley VC House” was made specifically for the show. It was a walk-in painting on the floor and walls and three canvases, each 120cm x 150cm. I don’t often work on ‘projects’ so this was quite a different process for me, I had to consider the whole environment that the paintings would be hung in. I’ve done this before, for the exhibition ‘The Future’ in the Coventry Biennial in 2017, but there I was responding much more to an existing architectural space. In 1 Godley VC House, artist and one of the show’s curator’s Tim A Shaw constructed a skeleton timber framework of his living space to scale within the gallery. Artists were each given an area within the simulated domestic setting to make work for. My work, “cntrl-shft-pwr”, is installed in the ‘bedroom’. I used a dark palette of red, green and blue (I was making these paintings at the same time as doing the residency so kept the palette consistent) that feels quite subdued – it’s a good example of how colour can affect environmental mood. The title of the work, “cntrl-shft-pwr”, alludes to a keyboard shortcut on a mac that sends the screen display to sleep – an immediate way of turning off the image information. Presenting painting as a physical encounter, by painting walls and floor, encourages us to ‘see’ it as a material object in an often-dematerialised world. This comes back to what we were saying earlier about the multiple lives of painting – the back and forth between reality, illusion, physicality and the virtual.

FUTURE

We are aware that you have an upcoming show at Flux Factory, New York. What can you tell us about this exhibition? Do you have any more exhibitions ahead?

‘The New Non: New Narratives in Non-representational Art and Abstraction’ will open at Flux Factory on 29th June. Curated by artist Jonathan Sims, the exhibition will show a diverse selection of work that engages with abstraction as a conduit for concepts and messages such as technology, identity, natural phenomena, mathematics, politics and artistic practice. I’ll be showing two recent works in ‘The New Non…’ In July I’m in a group show at DOK in Edinburgh, ‘Painting Inside the Matrix: Code and its Others’ curated by painter Ian Goncharov. The exhibition is a survey of the indexical signs of contemporary painting in the post-analogue world. In the autumn I’m in a three-person show at The House of St Barnabas in London with Peter Lamb and Remi Rough. ‘Interlude’ is a showcase of our three distinctive approaches to abstract painting as a legacy of the temporal histories of Modernism. We are making and/or selecting work with the unique architecture of the venue in mind and also working on a collaborative edition of prints as part of the show. It’s an exciting project that is generating some rich dialogues around our respective approaches to painting and the condition of contemporary abstraction.

15.06.18

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Charley Peters

Studio Visit