Sara Berman on using the problem to find the solution.

Since studying fashion design at Central Saint Martins in the 90s, Sara Berman founded her own fashion brand and worked as a design consultant to a variety of companies. Recently, she graduated in Fine Art from the Slade School of Art, and her fashion influences have become clearer in her art practice. “I am endlessly fascinated by manufacturing and its relationship to a particular time, as well as concepts of luxury and of modernity. I am also a keen observer of people as consumers.” The artist remarks, “The relationship between people and their belongings has intrigued me for so long that it has become my way of exploring how people define and understand themselves.” Berman’s works are populated by value systems, cultural symbolism, and time—and the viewer can expect a maze of games, pattern, and disruptions. We recently met up with Berman in her studio, to have a chat about the hexagon, harlequins, her work process and upcoming projects.

BACKFROUND

I find very intriguing that all of your works up till know have the same starting point, a background of geometrical patterns. Why are you interested in this particular pattern? How does it relate to your mathematical concerns?

I am far from being any kind of a mathematician, but I am interested in space. The hexagon as a pure mathematical form lends itself to a means of considering space, but for me it is also a bounded starting point for a painting. I find the hardest part of painting is knowing how and where to start and when to stop. I have used the hexagon as a tool to deal with this. I am interested in games, and the hexagon and the patterns multiple hexagons form, creating a structure that allows me to move in and around the work. Perhaps there is also an implied abstraction in any move I make to interfere with the pattern made by the hexagons. I enjoy the disruptive nature of other types of mark making that interrupt the hexagons uniform structural delineation.

One of the reasons you decided to study your Masters course at Slade School of Fine Art was the fact that Lisa Milroy was one of the tutors. How much has her input influenced your practice?

It’s a funny thing, but although I was very aware of Lisa’s work and have always had huge admiration for it, I don’t feel it was her work that directly influenced me whilst at the Slade School of Fine Art. Perhaps that is because Lisa’s teaching methods tend to be less about herself and more about the student. I should also point out that I entered Slade pretty much as a copyist. I had a head full of Chantal Joffe, Lynette Yiadom Boyake, Alice Neel… I thought that if I made paintings that looked like theirs then I might be OK. I wasn’t about to rip off Lisa, and then ask for her critique!! But now, with some distance I can see that we share many passions evident in our work (which obviously drew me to her) and I should have copied her more! What was actually much more important to me was her particular way of looking at things and her determination to help me see my work and what it was doing. She was a tough tutor but incredibly generous. I learned a huge amount from her.

In a recent interview with Marcelle Joseph at FAD Magazine, you mention that it took you a long time to realise that the foundation of your work as a fine artist was your background in fashion. From the production, manufacturing or branding process, in what ways do you apply your fashion background within your art practice?

As I mention above, I entered Slade as a copyist, and as a maker who didn’t know what their own work looked like, and I was fairly confused by the relevance of my background in Fashion. Clearly, I see the world through a particular lens, one that has been honed by many years working in a particular industry. But, as a painter and maker, I was keen to reconsider this viewpoint. I held making and fashion, separately in my mind. It was only as I gained confidence in my making that the fashion influences have become clearer. I have a passion for textiles, weaving, knitting, and the act of making. I am endlessly fascinated by manufacturing and its relationship to a particular time and place, as well as concepts of luxury and consumption. I am a keen observer of people as consumers. The relationship between people and their belongings has intrigued me for so long that it has become my way of exploring how people define and understand themselves.

In advance of making paintings, you prepare black and white preparatory ink drawings along with collages. Could you develop on this process? Why are you interested in removing certain formal elements – such as colour – in your sketches?

Actually I tend to employ that process once my making is underway. I start with the hexagons and let it roll from there. I don’t plan the paintings out at all. Once I get a bit further in I use drawings and collages and print-outs to play with various possibilities I might have in mind to solve the formal problems that arise. I do a lot of pacing and looking in the studio, and sometimes I get a bit overwhelmed. I enjoy the change of scale away from the work or the subtraction of colour to alter my perspective. It is also interesting that the solutions I find through collage and drawing don’t always translate in painting.

You base your colour combinations on Pantone home colour swatches, and your palette consists of recurring tonalities such as apple green. Are you interested in reducing your colour palette? How much does marketing/consumerist decisions influence your colour choices?

I love Pantone. I used it all the time when I worked in fashion, and because of that I have a sort of nostalgia for it. I am a very nostalgic artist. I really love the idea of an instructive colour plan – it’s a bit like those people in the 80’s who would get their colours read so that they would know what to choose when selecting their clothes. I would always wonder at that idea of a right and a wrong when it came to person style and choice. I suppose I like inflicting those boundaries on my work in a sort of conflict with conventionality or rules and the need of the painting to force its own way.

WORK

You are currently exhibiting in NYC, alongside Heeseop Yoon at Sapar Contemporary under the title “Solitaire”. The title directly references a well-know card game, in this context, how important is the term “play” in the show and in your practice?

Play is a very important aspect of my practice. Having certain rules in play (which I totally cheat on if choose-makers prerogative!!) also creates a mental separation between the “what” and the “how”. I really lean on that separation as I have a tendency to over-intellectualise work that isn’t going well, which doesn’t make for good work in my opinion. But actually, it is always the surprising or unresolved parts of the work that teach me the most, and create the space for new consideration. I suppose I use rules in order to find ways to break them.

Many of your pieces are informed by the weight of history, and how certain materials have travelled from east to west and viceversa, such as your embellished 1940’s Iranian textiles. Can you explain this idea further?

I am really curious about value systems, cultural symbolism, and time – how objects move through the world and exist in it, and how all this affects our understanding or appreciation of them. Notions of rarity or “foreign-ness”, and why we attach this value to certain things, also really interests me. I grew up pre the Internet, at a time where things were slower, and distances seemed greater. There is something really intriguing about the idea I have experienced another time and place and how I have a completely different understanding of certain objects [or things] because of that. It’s like time travel with cultural baggage! I am particularly into textiles because the method by which they have been made and manufactured – woven, knitted, etc. – is very rooted in a certain time and a place, which influences their value and our relationship with them. Their domesticity also interests me – the way they are used, their inherent usefulness and the humanity they are imbued with because of this.

Your works are mostly constructed in grid formations that can be assembled in a variety of configurations, paralleling board games, which precisely allow a variety of moves and options under a limit of possibilities. How do you determine your compositional decisions? Are you interested in assembling these grids with a problem left unresolved?

I respond well to boundaries. I think that coming from a design background, I have a great respect for using the problem to find the solution. I use the panels as compositional tools to alter the spacial and formal considerations of the work in a way that can totally turn the work on its head. Sometimes, I do this only with the intention of helping me temporarily see the work differently. Resolution is becoming a more open idea for me. More and more the work resolves itself though a serious of discoveries which reveal themselves as it progresses rather than by applying learned and conscious methodologies. Perhaps more than anything else, I am most interested in the parts of a work that surprise me (and of course you can’t surprise yourself on purpose!). There is something about the panels and their potential flexibility, which gives the work a contained space in which to surprise itself.

You have developed a recurring harlequin symbol in your works, with apparent trickster qualities. How did this figure emerge? What is the role of revealing and unrevealing in this character?

It’s funny because my harlequin came about as a real combination of things. I was wondering about the role of clothing in my work, and feeling fairly overwhelmed by how loaded that is for me. I spent a lot of time enjoying Picasso’s Seated Harlequin at the MET, and decided to steal the outfit. It reminds me of the clothes I used to make -the white collar and Argyll knit. The harlequin/Argyll grew from there, and has turned up in some of my subsequent paintings and lint works. I do enjoy the idea of the clown or trickster. It has a sort of uncanny quality, as it gets lost in its surroundings, seen and unseen, known and unknown through playing with pattern. But there is also a real attraction to the complication of the patterning and the possibility for play within the making of the work itself.

In what ways do you visualise interior spaces, furniture, and objects as bodily figures?

The spaces we occupy – in particular the domestic, the inhabited or those we hold most clearly in our minds as belonging to us- become extensions of self. They contain the things we have gathered around us or recall most readily as well as the practical mundanities of everyday life. I often consider that an object designed to be used by people such a chair for example- can have a bodily aspect. In anticipation of serving the absent body, it can act as a stand in for the very thing it is there to service. We can read spaces in the same way that we can read clothing, as a set of signifiers that go someway to describing the bodies that exist within them- even when the body is absent.

You source lint fibres from washing machine remains, which you join with hairspray and then hand paint, assembling lint sweaters not fit to be worn. Is this method the reverse of your painting process?

I am really drawn to the conflict and humanity of these works. The machine dictates how they will be formed and coloured, but they are inherently made from human detritus. Intellectually, it amuses me that my paintings deal with the uber curated, whilst the lint is lowest common denominator base reality. Also, I am really interested in ideas around time and making. There is something about time, making and location at the very heart of this work which is very structured. The particularities of these pieces are created through a process which is informed by the location of the machine (in terms of the people who’s clothing dictates the colours) and the time which will dictate the number of layers and how much lint is in each work. So a real balance of the random and the structured.

FUTURE

From Bauhaus aesthetics to product or furniture design. Where do you find your artistic stimulations?

I am getting less and less discriminate! My interest in Bauhaus is very linked to my interest in manufacturing and ideas around value. Likewise, my obsession with rugs, but actually, I am a bit of a magpie as far is inspiration goes, and I am very influenced by the places I go and the things I see. Sometimes, overthinking what is turning me on takes all the fun out if it.

Do you have any future projects lined up that you can share with us?

I do have a few nice things coming up this year, but last year was crazy, so I am being really mindful of allowing myself time to make work at a pace that will allow it to develop with respect for time and making.

07.02.18

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Sara Berman

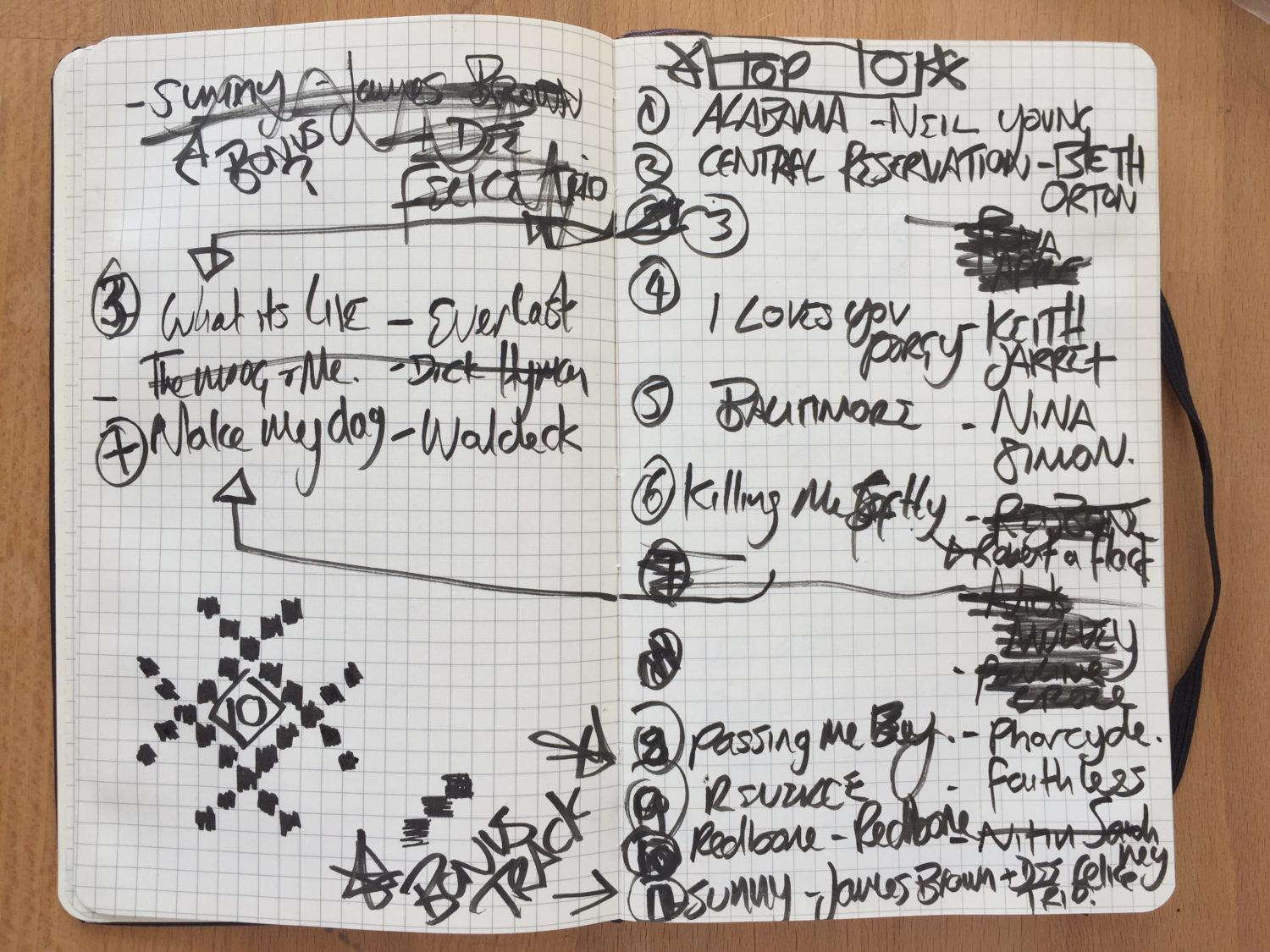

Mix