Explicit interactions of colour.

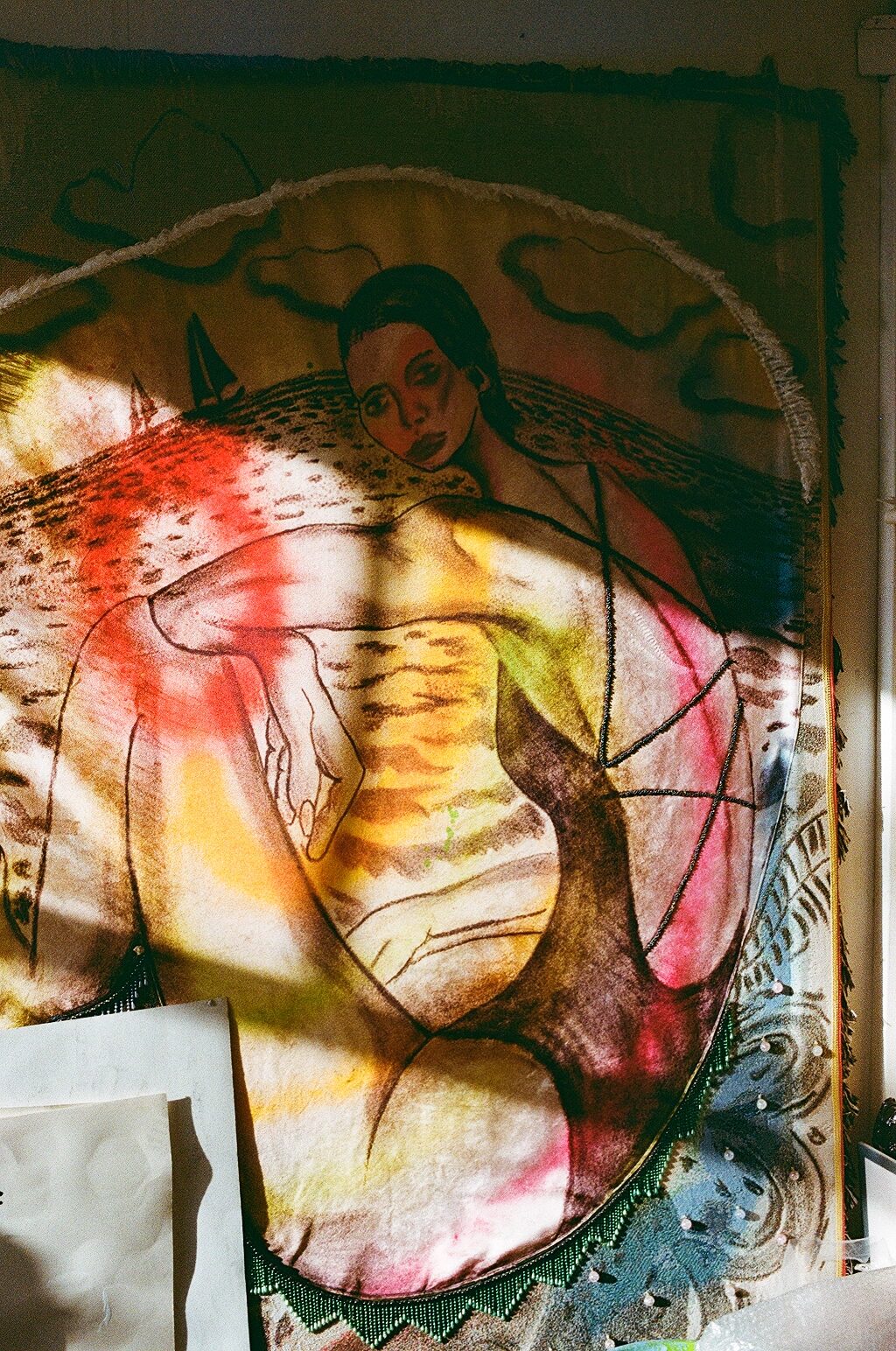

British artist Helen Beard takes on fluid lines, sensual shapes and vivid colours to celebrate humanity’s most intimate pleasures. Her erotic landscapes go beyond associations of gender and race to embody diversity and equality. Following university studies at the Bournemouth & Poole College of Arts and Design, Beard went on to build a long-lasting career in the film industry. Fifteen years of professional expertise inform her artistic production, where she appreciates precision in her pictorial executions. Although there are frequent depictions of genitalia, from close-crops to wider shots, she puts primary attention to generating a sense of connection between subjects and viewers. The interaction of bodies displayed on her canvases is meant to arouse no more erotic desire than emphatic interaction. Besides painting, the artist is also engaged in making collage, sculpture and needlepoint. Tapestry holds a personal connection to her grandmother, from which she learnt this traditionally female and meditative pursuit. It is a therapeutic process Beard finds enjoyable despite its time-consuming nature. The artist is graphically minded and unapologetically open about female desire. Her work, which lends itself nicely to digital sharing, has often encountered pushbacks from social media platforms like Instagram due to their restrictive guidelines. Looking ahead, Beard finds excitement in experimenting more with maquettes as well as text. She’s also focused on finding alternative ways of transferring her stylistic signature to sculpture and expanding the provocative qualities of her work within different cultural settings.

BACKGROUND

When discussing your background, you bring up a critical issue, that of class inequality with regards to access to the arts. Could you elaborate on how you were able to persevere and pursue a creative career without financial backing from your family?

I was lucky! I managed to get a free arts education right before the introduction of student loans. Coming from a background where art isn’t even considered as something you can do for a living is always hard. With the prospect of an incredible amount of debt, and it is easy to understand how untenable it becomes for working-class kids to study in this field. This has had and will continue to have a big impact on diversity within the arts.

What is one element of your artistic practice that parallels the projects you undertook as an artistic director in the film industry?

I was assistant to a production designer and then a wardrobe mistress in the film industry for most of my commercial career. They put great emphasis on perfection and it had a parallel influence on my paintings. I am meticulous about keeping the surfaces clean and perfect!

Your compositions include almost seamless transitions from one color or shape to the next – it’s intriguing to visualise it’s achieved with a paintbrush, as it’s very graphic! To what extent do you feel that your background on the topic informs the way you paint?

I studied graphic design, and the art that I most admired as a young woman was always very graphic: people like Patrick Caulfield, Gary Hume and Michael Craig-Martin. I guess I am graphically minded, I think mostly about shape and form and colour when painting.

WORK

You have mentioned your process starts by sketching, often based on pornographic stills facilitating your study of angles, bodies and positions. Are genitals not an afterthought, but the focal point of your paintings? During the preparatory stage, do you attend to them first?

Sketching the angles, bodies and positions is important, but the thing I am most trying to achieve is a sense of connection – a feeling suggested by forms and colours’ interactions. Body parts, genitalia or not, are irrelevant.

The color palette of your canvases is rich and harmonious. One constant is that you avoid fleshy tones. What is the reason behind the effort to disassociate your nudes from skin color? Do you think it helps universalize the viewing experience?

I do use fleshy tones sometimes, but not to depict a whole person. The use of vivid colours takes away race associations and it is a deliberate act to discourage prejudice.

From up close, your canvases are intense interweavings of color, but from afar, human forms begin to take shape, that is when the viewer is granted voyeuristic entry to the scene. Is this transformation that occurs relying on one’s standpoint done to protect your content from associations that sexual art often carries – dirty, profligate, shameful? Is it important to you that the subject matter changes depending on where it is viewed from?

To know my paintings work on different levels and viewpoints is good. Hopefully, they also describe the visceral as I am unapologetic about female desire, without hiding it. Women do often get labelled dirty and shameful when talking about sex. That’s why it is important to make some very direct and explicit works, as well as more abstract ones.

Your works are all about connections between people, without focusing on specific genders, identities, races. At a time when explicit pornographic images are more easily accessible than ever before, do you think that it is the beauty in the simplicity of the entangled bodies on your canvases making them so resonant?

Yes, I am interested in beautifully simple connections between people regardless of race, gender and sexual orientation. Even though sex is a universal and basic instinct keeping the human race alive, it is also diverse. At its best, it’s about enjoyment as well as the desire to feel loved and cared for. I value equality and diversity, always striving to depict sex in as many forms as possible.

Due to the sexual substance of your works, it was surprising to see them digitally displayed by W1 Curates, on consecutive large screens. How was the sensation of having your art be so publicly unveiled?

W1 Curates was amazing! The images were censored because of the setting on Oxford Street in central London, but it worked really well: it suggested the subject matter without revealing too much.

Social media is a brilliant way to promote artistic work, and your digital presence on Instagram is quite active. But the platform is also problematic for artistic expression, because it abundantly censors the naked, usually female, body. Have you faced such issues on this or any other online platform?

Using Instagram can be problematic at times. My artworks are not photo-realistic and I could argue they don’t show sexual interactions at all. Instead, what they are is flattened abstractions of colour and form! Negative space is as important as the depiction of bodies. In a sense, they relate more to landscape paintings. That said, they do get censored and taken down occasionally.

From HIV education and prevention, to helping house the homeless, there is a long list of causes you care about and that you have fundraised for. What is a charity you want to work towards supporting which you think it’s essential for us to be aware of?

I am happy to support charities as I have done so far and I hope to continue. I would also like to support young artists, as this is an area we fall short on in this country. Our government does not value arts as other countries do.

Currently you are working on a needlework project, collaborating with Fine Cell Work, an organization providing creative opportunities for prisoners. Were your paintings too explicit to be allowed, pushing you to brainstorm about how to best express in words what your canvases evoke? How exacting is the process of ‘undoing everything you ever wanted’? Can you share some examples of what it is you want to be undone?

My most recent project ‘Everything I Ever Wanted Undone’ is a departure into typography, but I didn’t do it because of the constraints of working with Fine Cell Work. It is interesting how the prefix ‘Un’ changes a mostly positive word into something entirely different. The words I have chosen relate to basic human needs like being loved, settled, seen, heard and equal. Things that humans strive for, and suffer when they can’t obtain them. I want to highlight that it is often detrimental to people when they lack them, as they are of ultimate importance to the human condition. Originally, it came to me from undoing some of the needlepoint pieces that had gone wrong. It was frustrating having to unpick the work I had put so much effort into. But I consolidated the idea after seeing refugees leaving their war-torn countries on boats. These unsettling images made me realise the horror of their situation, going to places where they are likely to be unseen and unwanted. I want to highlight that in this piece of work.

You move across a variety of mediums, from painting, to collage, to sculpture, to needlework. Which one do you find the most demanding, which one is the most time consuming, and which one do you prefer working with?

Tapestry is by far the most time-consuming process, but I love the repetitiveness of needlepoint. I learnt from my grandmother and I find it very meditative. Traditionally, it is a female pursuit, which I like too. Large scale oil painting is incredibly physical and encompassing, like dancing. I enjoy the contrast between the two disciplines as they have a similar therapeutic effect on me.

FUTURE

Your painting has had more exposure than your sculpture, but you have been operative on that front, with ‘I Have Made My Bed, I Will Lie In It’ (2019), for which you used retro sex toys. From afar, the piece resembles a traditional Indian meditation bed, only the vibrators have replaced the nails.You have also made other pieces with these, like ‘I’m into you, Are you into me?’ (2009). Are you going to continue with such sculptural projects, and if so, what are your plans for that?

I really enjoyed making the sculptures – those were old ideas I finally got to realise! I imported the vibrators for my bed of nails in 2000 already knowing what to do with them. I wanted it to be a very simple piece of work. I am also excited to soon make sculptures based on my paintings and experiment with maquettes and intertwined bodies. Hopefully, they will be like an amalgamation of Niki de St. Phalle’s ‘Nanas’ and Rodin’s ‘Kiss’, or a game of Twister! I haven’t ever sculpted before; I hope I can realise these ideas!

Do you intend to explore more traditional sculptural mediums like bronze? How would you incorporate a material like that, traditionally associated with masculinity, roughness, and the realm of public art, into your work? Will you work towards ‘softening’ it? Will it be solely through shape, or will you employ your trademark application of an energetic color palette?

Colour, texture and brushstrokes will definitely be involved because of their importance in my paintings. I hope I can translate these elements to my sculptures too.

You have a residency at Reflex Amsterdam coming up, which will culminate in a solo exhibition in September 2022. Conceptual artist Michael Craig-Martin will be a resident right before you. Similarities can be drawn between your works – the bold colors, the large canvases, the close-ups. Do you think this style of creating is taking over in our digital world and is more influential now than it was when you started?

I mentioned Michael Craig-Martin before as being an influence, but I don’t think the style has come about due to the digital world. I think it works so well on social media because of its graphic element.

What are your objectives for your time there? How do you think Amsterdam, with its renowned relationship to sex work, voyeurism and pleasure will affect the works you create? Will this be an opportunity for you to create more provocative works than ever before?

I am very much looking forward to living and working in Amsterdam next summer. It will be a chance to experience a new culture and I am sure it will inform my work, but whether it will be more provocative I am not sure. Let’s wait and see!

27.08.2021

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Helen Beard

Interview