A wordless diary of experiences is embodied in Clare Price’s paintings.

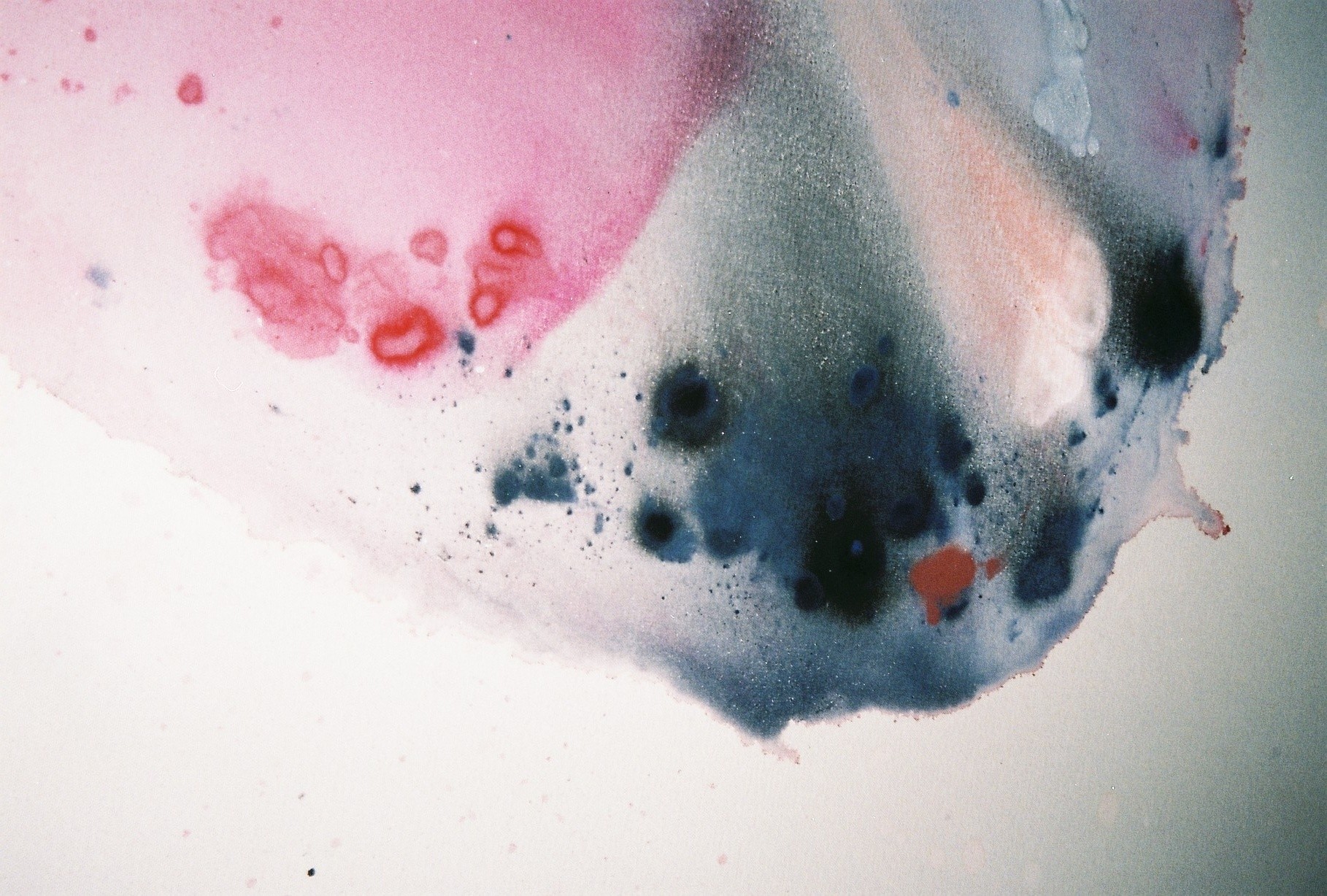

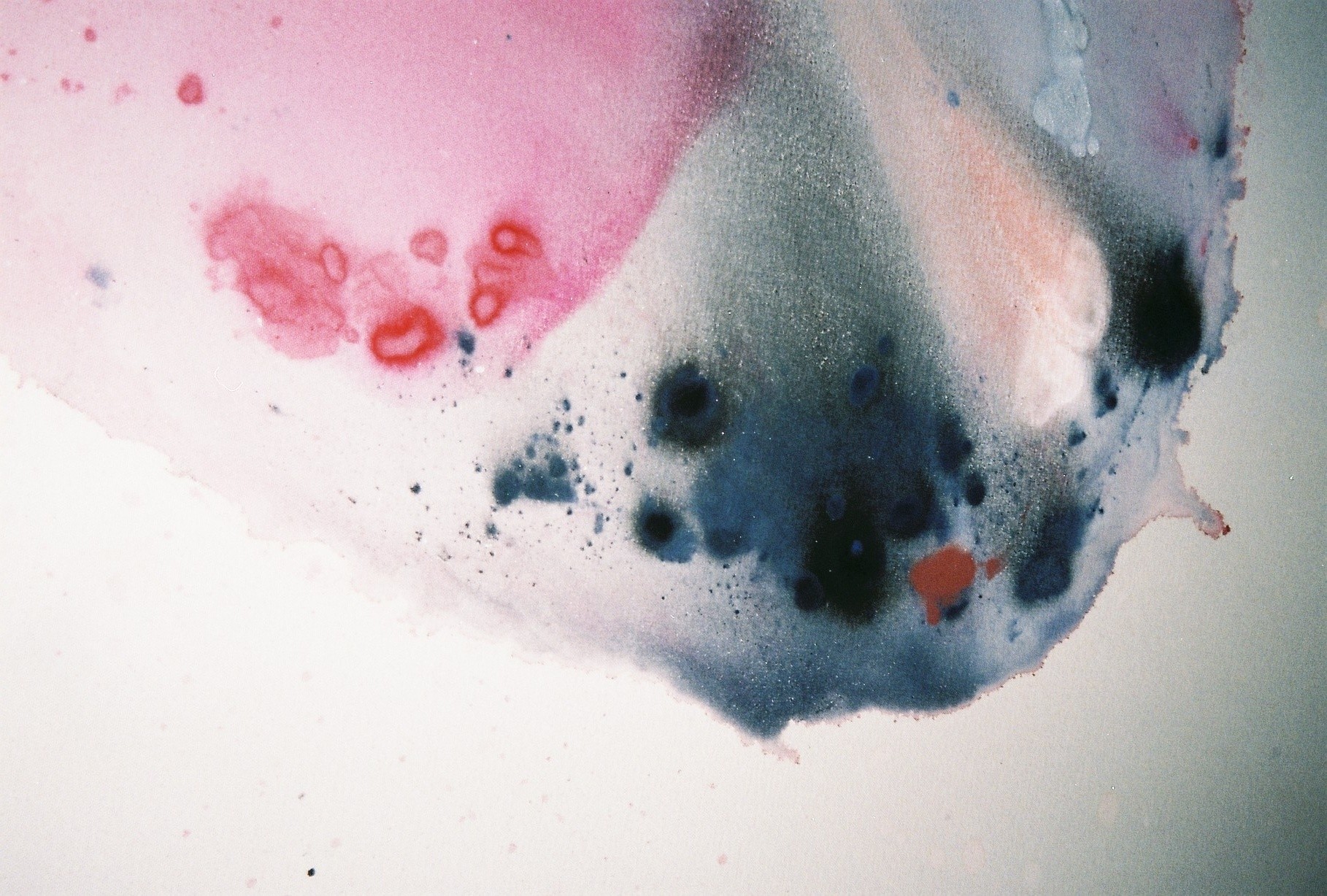

Opening the door to the studio of London-based artist Clare Price, I am confronted with what looks like a wordless diary: a red chair covered with remains of painting drips, a pile of clothes hidden under the table, a window reflected onto the glossy surface of the still wet canvas on the floor. Truth is, it is not the first time I visit this space. I have been fed to imagine it through my phone’s Instagram feed, which has been following Price’s daily squared-size acrobatic poses in this same white walls and grey floors I step in today. I always had the feeling that Price was intuitively guided by her work in the process of its making. In this, the artist proceeds to paint through pouring, dripping, flicking, and slipping. “I don’t cheat” she says, meaning she doesn’t rework the pieces once these are made as they are so deeply connected with her experiences, feelings, and emotions. As she mentioned to Jon Sharples from the Simmons and Simmons painting collection in a recent panel discussion, “it has taken me 47 years to make the work”. The mood is just as Clare describes it through the private space of her Instagram posts: #fragile, #lighter, #scarred, #allthefeels —a touch #incandescent and even #impossiblysad. There are many artists using Instagram as a tool to display their work, however Clare has taken it a step further by admitting that the grid on Instagram has allowed her to make sense of things. “Paintings should be felt” Price says, as I reach for my phone to document the studio space and take some notes. It’s true: everything in here seems to embody all of the experiences that are such a big part of the artist’s life: abuse, trauma, oppression, healing, a reclaiming of the self… and these no doubt come out in the work, consciously or unconsciously. That said, the act of painting is an emotional and intense one for the artist, a process that allows her to be released, where the making and viewing is both a refuge and a portal. It is a deeply personal state where she explores cyber magic, and where painting functions as an amulet, a spell, or even a super power. I sit down in a chair surrounding her newest piece that is drying on the floor, where we talk about how research comes through the body and why her paintings are an autobiographical marker of each day.

BACKGROUND & PROCESS

When undertaking an MA at Goldsmiths, artist and tutor Mark Leckey got you into the idea of ‘using your body as a vehicle for your obsessions’. Was this a pivotal moment of realisation for you?

It was really important, yes, and even more so when he said, “art comes through the body and the life experience”, in terms of both accepting and allowing my experiences. In my work and in my life, it was very freeing. Mark is really psychedelic in his thinking, and I am not sure I would have survived Goldsmiths had I not been lucky enough to have him as a tutor at the beginning.

Your process is conducted by actions such as throwing, pouring, or spilling. Does it carry you into quite an animalistic state?

Kathy Acker says “I need to be invisible and without language – animal”, and that really sums up my relationship with painting. A friend of Joan Mitchell described her studio as being “like a place that an animal goes to for safety”, and I relate to that absolutely.

Would you agree in saying that there is a sense of choreography, a mark of dance, and a rhythm in your process in which the paintings get liberated?

The works are now almost always a direct trace of a performance realised in one act. I love to dance and am interested in it as an art form – I think another safe space of release for me has always been the dance floor, particularly as a little raver when I was younger. There is a connection there, one that I am starting to explore further in the photographs and some experiments with moving image. I wrote this about the recent paintings: “Using colours drawn from Turner –to eye make up – to rave they are fragile sensual explosions; the recording of an unseen dance.” I think that sums it up.

1 Research has to go through a body; it has to be lived in some sense – transformed into some sort of lived experience – in order to become whatever we might cal art.1 Mark Leckey interview by Mark Fischer, Kaleidoscope Magazine, Kaleidoscope.media

WORK

Your work can be read through a personal level, but also through a global magnitude, these having an aura of geological or even cosmological connotations. Are this ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ associations intended?

When painting one is dealing with “stuff” that exists in the earth, in the stars, and in our bodies. Though there is a clear manipulation of the paint, there is also an element where a large wet mass of water and paint is left to dry on a canvas, and the materials and temperature decide how things are going to form, which is both very bodily and very geological. I was looking at images of the universe, and though the paintings are not depictions of that, I am not surprised there is that feeling to them, which has found its way into the work. There is a delicious quotation (one I love) about painting that touches upon these things, as well as on the power of containment of the stretcher: “This is the house with its windows and doors that open onto a universe.” I don’t, however, think any of this is intended; rather, it has been like a feedback loop whereby the work has started to reveal things that I did not consciously impose upon it.

When coming into contact with your work one cannot help but think “I want that orgasm too”. However, does this depiction of provocative pleasure threaten you in some ways?

Ha ha, well, that has been one of the readings of the paintings that they are orgasmic. My friend Nora Hansen said “I want that orgasm” about one of the more intense paintings which made me laugh a lot. Certainly, the paintings address control and release. There is there is a sexuality to them, for sure. The images of their making that I share in snippets on Instagram are very bodily – but I am not a figurative painter 😉 The works may be experienced in many ways; the recent paintings have also been likened to galaxies and big bangs. If they are sexy then I do not feel at all threatened by that – in fact, I hope that they are. I wrote this on Instagram (I have found a way to write through Instagram) and it feels really important to me: “I hope it is visceral, I hope it is sexy, I hope it is vulnerable, I hope it has a power” I feel protected by the paintings in some way and when they are out of the studio I can feel vulnerable – I have always seen painting as a space of refuge and a portal, in both the making and the viewing. They do not threaten me, and if others find them threatening, then that is about them – the same goes for the photographs.

2 21 Bolt, B (2010) Unimaginable Happenings: Material Movements in the Plane of Composition – Zepke, S. and O’Sullivan, S. Deleuze and contemporary art. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. P271

What can you tell us about your usage of lo-fi gadgets, such as the bluetooth button you use when photographing yourself?

I love a lo-fi gadget, and I enjoy that the button cost £12 and what “spilled” from it had such a profound effect on my work and my life – Budget cyberfeminism – it hasn’t even needed a new battery in a year and a half, and it is now covered in paint.

Your application of translucencies and neon tonalities resonates with digital processes. Do you think that this technological approach subconsciously comes out of you, considering you’ve worked in the TV industry, and in motion graphics prior to becoming a full time painter?

I would say that the digital is a part of the DNA of the work; all the experiences that we’re such a big part of my life are embodied, and no doubt come out in the work, consciously or unconsciously.

Has the scale of your work grown larger until reaching a point that relates with you in a physical sense?

A scale that I often use is 153 cm x 178 cm, though before I found this scale, I was making larger works. The original stretchers of this size were absolutely bought with thoughts around the body, and their relation to my body. I unpicked and re-stretched some of them so many times over many years that it is a scale that I understand so well physically, as well visually. I think this is crucial to how I interact with them as a painter.

For the past year, you’ve developed performative photographs in which you reveal intimate layers of yourself merging with your work through your social media account. Was there a personal necessity to make these images?

Yes, somebody said that it was necessary to make those works, that it was difficult to put them into the world, but necessary to make them which is about right. They have felt urgent; making paintings has been a way of living through a period of great fragility but also growing in personal strength. There are some things about the photographs, about which I am starting to be more explicit. It is new and hard to write about, so if you will forgive me, below is what I say in my statement about them – Exploring the dynamics of fragility and power, control and release, the photographs engage with notions of safe spaces, both physical and online, in which to make and disseminate the work. The photographs seek to “spill” and un-contain the sensuality, sexuality and lived experience that the paintings hold within them. They explore the release of this self from the “bloc of sensation”, as Deleuze would call it, of the painting’s frame. In the photographs I perform the affect that is present within the work, they are posted in sequences which when animated reference both dance and choreography. Reclaiming the feminine body and the female gaze within patriarchal structures, the photographs were originally displayed on a private Instagram account, in which the vulnerability around the autobiographical references of the paintings and photographs could be released. The photographs engage with ideas around Cyberfeminism and are deeply personal dealing with experiences of abuse, trauma, oppression and healing, a reclaiming of the self.

Silver heels, and painted jeans. What attracts you particularly towards these props, which you’ve decided to include in your performances?

Pivotal to this is something Mira Schor writes in her book Wet: “A friend of mine described in terms of reverence and sexuality the rags she wears when she paints. Every layer discarded and replaced by Street clothes is an added layer of anxiety and loss of intimacy with herself” 3. In the same way, my painting clothes are a key or have some kind of agency. I played with many things, including wrapping myself in the paintings, but in the end there was something in the painting clothes and how they became caked over time. There is a gendered thing about the work clothes that I enjoyed subverting (previous posts were with my work boots or lucky Nike studio huaraches, covered with ten years of paint). The silver shoes stuck. I was thinking about the intertwining with the performance of the private view, but also I just love those shoes and they have a power – or I gave them a power – in the photographs.

There’s an aspect of healing in this performance, in which you paint your body as if the paint will protect you. In this context, what’s your relationship with the materials you use, and do you believe in their therapeutic qualities?

I very concerned with ideas of safe spaces both in terms of the studio and the private Instagram account. In these conditions, things have been able to “spill” with me. When removed from these spaces, I am interested in the idea of paint to protect. This has manifested in several ways, with early Instagram works in which I painted onto my naked body (another artist talked about these painted marks as being like spells to protect me which I really liked). This is also an important factor in the photographs whereby the painter’s clothes protect, and allow or give permission to enter a different state. I took this further by wearing a dress by the artist Nora Hanson, who makes garments that have super-powers. I had painted on the fabric and this acted as a protection for me at the ‘Fragility Spills¡ private view (I find these occasions very challenging to be honest). I am not sure if I believe materials are intrinsically therapeutic, but I am interested in using them as an amulet, spell or super power to protect me.

3 Schor Mira (1997) Wet: On Painting, Feminism and Art Culture, Duke University Press P124

As a middle age single parent, has the fact of exposing yourself entirely through social media in the form of vulnerable, feminine, and erotic postures given you power, visibility, and a certain level of authority?

Curator and writer Cairo Clarke wrote this in her essay “Performance, Precarity, Power”, which accompanied the show Fragility Spills at ASC Gallery, and it sums up so much: “Reaching this point comes through owning, acknowledging and accepting our lived experience in all it’s brilliant and traumatic forms, shedding the skin informed or inscribed upon us and wearing our own. For Clare Price, the process of getting to this point has been showed publicly through not only her paintings but the gathering of images publicising her process and its performativity – exercising her right to appear and be valued, performing and turning it into a creative energy source” In making these works, in these moments of what is at times extreme fragility repeating them rhythmically insistently and urgently, like the painting practice a cyber magic has occurred, and I have found a voice. I have no idea if I do have authority – that seems crazy to me – but through this work there has been healing. This is emotional and intense and a lot to get my head around.

I believe your titles have secret autobiographical connotations. Is this ‘coded’ language a parallel to your dyslexia, and a continuation towards the nature of the private/public element of your practice?

I hadn’t thought about it in relation to my dyslexia, and that is interesting. I have always been interested in paintings as a marker of the time of their making, whereby the affect imbued in the studio might in the best cases be flung back in a bodily way to be felt viscerally by the viewer. This has happened to me with paintings that have been important for me (I am thinking particularly of Joan Mitchell’s show at Hauser and Wirth in 2007) so in this way, paintings are like a wordless diary. Mary Heilmann talks about paintings as being an “autobiographical marker of each day” 4. In the past, I had titles for the paintings but they felt too “heavy”, like they were pinning down the works too much (my view is that paintings should be “felt” and the words were hindering that) so now, the titles are encrypted autobiographical references that allude to the body, sex, and the time when the works were made.

4 Heilmann, M, 1999) “Looking at Pictures, The All Night Movie Zürich: Galerie Hauser and Wirth

The last time I visited your studio, we spoke about forgotten woman, such as artist Joan Mitchell, along with artists Joseph Beuys, and J. M. W. Turner. Where do you source your inspirations and who are the artists you get excited about?

Here is a list from the top of my head, though I am sure I have left out so many important ones and will kick myself later. I don’t know how I find them – I think they find me: Joan Mitchell, Beuys (particularly the watercolours), Turner, Gillian Ayres, Helen Frankenthaler, Mary Heilmann, Blinky Palermo, Linda Stupart, Mark Leckey, Philip Guston, Jeff Koons, Agnes Martin, Willem De Kooning, Carolee Schneeman, Lynda Benglis, Ana Mendieta, Laura Aguilar, Jemima Stelhi, Georg Baselitz, Sigmar Polke, Tracey Emin, Samuel Beckett, Ad Reinhardt, Rihanna, Ariane Grande, Frank Stella, Ingres, Beckett, Prince, Michael Clark, Ross Bleckner, Lynda Benglis, Kathy Acker,Yvonne Rainer, Audre Lorde, Francesca Woodman and Jonathan Lasker.

Your practice has been rooted in painting for 30 years. Would you consider yourself as a painting romanticist?

Absolutely, wildly so.

FUTURE

Will your performances continue as private ones, within the ‘safe spaces’ of your private Instagram and your studio, or will they expand into the public realm?

Instinctively I would say that will never happen, but I have learned not to say never. I might yet find my inner performer, but at present she is hiding quite deep inside the safe spaces. Since writing this, I went to an amazing drag king night “King of Club”s at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, hosted by Frankie Sinatra. This followed after a really moving talk and work in progress by Nina Wakeford for Art on the Underground, involving a work that included memories of a club called the Market Tavern in which Frankie had been a key part. It is fresh in my mind, and I found it really moving, intoxicating, vulnerable and life-affirming and have been considering the need for those of us who feel “othered” in some way to perform as an act of retaliation. So, I am thinking about that but for now the performances are hidden. Just making paintings in the studio is challenge enough, to be honest, and the paintings are best when I leave the drama to that space in private.

You described feeling a sense of clarity, peace, excitement, and openness. What are your expectations towards the evolving of your practice in the close future?

I feel all those things very strongly. I also feel that I have a lot of processing to do, as what has transpired in the last few months has been incredibly intense and rapid, both personally and in the work (these things are, of course, inextricably bound). I don’t know where it’s going. I will keep painting. I will keep taking photographs, and perhaps some moving image work, and I hope that it follows the best way of making work – where the work starts to guide you. To quote Joan Mitchell (with who am quite obsessed!) “I use the past to make my pictures, and I want all of it and even you and me in candlelight on the train and every “lover” I’ve ever had – every friend-nothing closed out-and dogs alive and dead and people and landscapes and feeling even if it is desperate-anguished-tragic-it’s all part of me and I want to confront it and sleep with it – the dreams – and paint it”

01.04.19

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Clare Price

Interview