The Keeper of the Balls

Sphinx is female. Scorpion is male. Where is this perception coming from? Is it just me, because I speak German and the article for Sphinx is female and the one for scorpion is male? Can it be that simple to just explain it linguistically. But here’s a question I have been asking myself forever: why and how did gendered articles come to be and who decided what was female, male or neutral? Down the rabbit hole that we call the internet, I learned that while the German language has assigned the female article to the Sphinx, it has become customary for archeologists to use the male article because the majority of Sphinx found to this day represent a male figure. The Sphinx is the only female gatekeeper I can think of, though I just learned that this is only true from a Greek Mythology standpoint, not the Egyptian. The female, Greek keeper of secrets is malevolent. Anyone who cannot answer her riddles is eaten or killed by this vicious creature.

The scorpion, in my vocabulary a gendered word and in my associations a male creature, is in fact believed to have been created by Gaia – the personification of earth – according to Greek mythology. While hunting with Artemis, the goddess of hunting, Orion (a man famed for having been blinded after abusing the daughter of someone who was not going to let him get away with it unharmed) is believed to have threatened to kill every beast on earth. This is why Gaia created the scorpion. This is why the scorpion killed Orion. Both Orion and the scorpion landed amongst the stars and to us are mere symbols in the sky. Not mythical or politically loaded. Just lines between the stars that form an image.

Here’s the first thing that comes to my mind when I think of these myths: they are about strong female figures. Artemis, Gaia, the Sphinx. And yet, the stories that are being told are mens’. It is the myth of Oedipus, where we learn about the powerful Sphinx and the story of Orion that teaches us about the creation of the scorpion – in a story that so casually places raping one woman next to a friendly hunting trip with the goddess of war. And this is exactly how I felt about women’s football, until last month.

During the FIFA Women’s World Cup last month, I realised that never before have women’s teams been given as much attention as the men’s usually do – and by all means, don’t get me wrong: they still don’t. But the games were broadcast on popular (and free!) TV channels and spoken about regularly on radio stations. The news media extensively covered the championship. Or did they? Did the media cover these events in the same way they would men’s football? I have had several discussions on the subject of men’s vs. women’s football these last few weeks. And no, we don’t believe that equality means getting everything exactly the way the men do, but it means being respected in a way that is as profitable to the women playing as whatever men get is to them. A lot of the media was not about the games. It was around the players being female and this being women’s football. It was about congratulating each other on how far equality has come, that we are all now suddenly watching women’s football in the same way as everyone watches men’s football. But we don’t, and we haven’t come far enough. What was big on the news was Megan Rapinoe, the captain of the US team – for all of you who live under a rock – on the eve before the final, talking about “respect” and how two other championship finals had been set to take place on the same day as the women’s world championship final. A lot of people took this as an overreaction; “It’s not even taking place around the same time.” Men’s World Cup final is a day where the world literally stands still and nothing else happens. Not before, not during and after, we have no time for anything else: we have to celebrate (so much so that the organisers of a race Holly took part in last year packed up and closed the site early to watch the men’s England vs. Sweden QUARTER final!). Don’t women deserve the same “respect”? Or are we just already dismissing its importance by saying: “I think people will be done celebrating within two hours. And maybe they are then in the mood for some other football.”

Holly Daizy Broughton, She Performs co-founder and curator

But this is just the tip of the pyramid, so to speak. While I was aware that women’s football teams usually are financially carried by the men’s football teams, I was probably naive to think that the ‘pay gap’ for the championship prize money was not as big. I’m a defender of not seeing the pay gap in sports between women and men as a direct offence against the female sex. A male handball player makes less money than a male football player. The income of teams (and each sport in general) is strongly based on the public’s interest in paying to watch the game on TV, pay overpriced tickets to see the games and buy the merchandise. Of course, it’s never as black and white and the pay gap isn’t just missing merchandise sales. It is a historically gendered audience that has decided who can and should not play football or other sports. BUT, then I learned that the US women’s football team’s participation in the 2015 championship cost them more money than they won ($2M) FIFA announced that it would double the money spent on the women’s championship to $30M total, which means that the US took $4M home this year. But they also announced that they would raise the total prize money for the men’s championship in Qatar in 2022 to $440M! Never mind the ridiculously huge gap there already is, and that one could argue women got a 100% raise while men ‘only’ got 10%. In absolute numbers, men got a $10M higher raise than the total prize money that women can get (and that is after they doubled it). In anticipation of the next world championship in 2023, FIFA’s president Gianni Infantino pledged to double the women’s prize money again. First, the men are getting $40M more and women are getting $30M more. But – and here IS a but – he also wants to add more women’s teams to the pot. From 24 teams ‘splitting’ $30M to 32 teams ‘splitting’ $60M – you do the math.

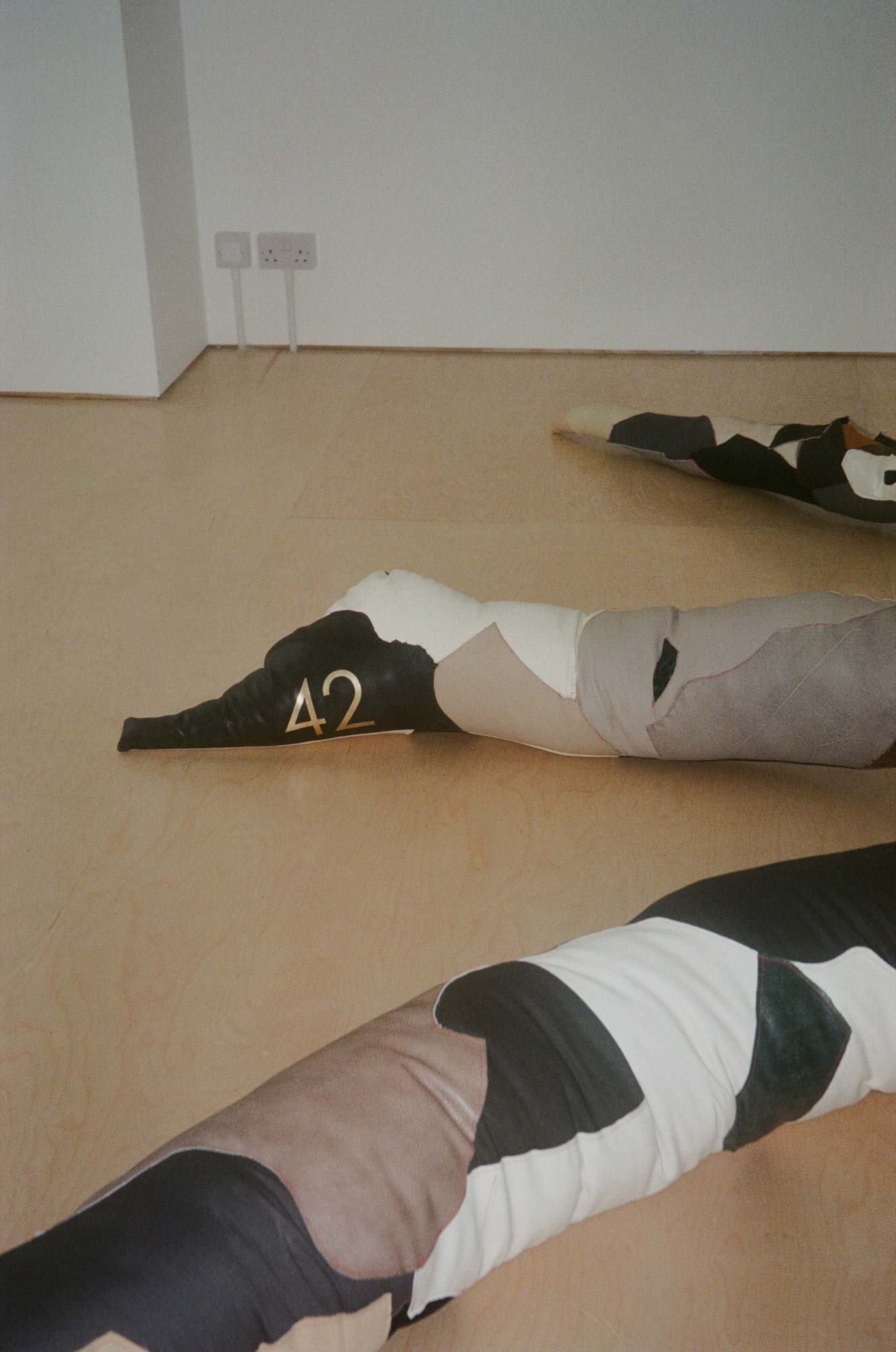

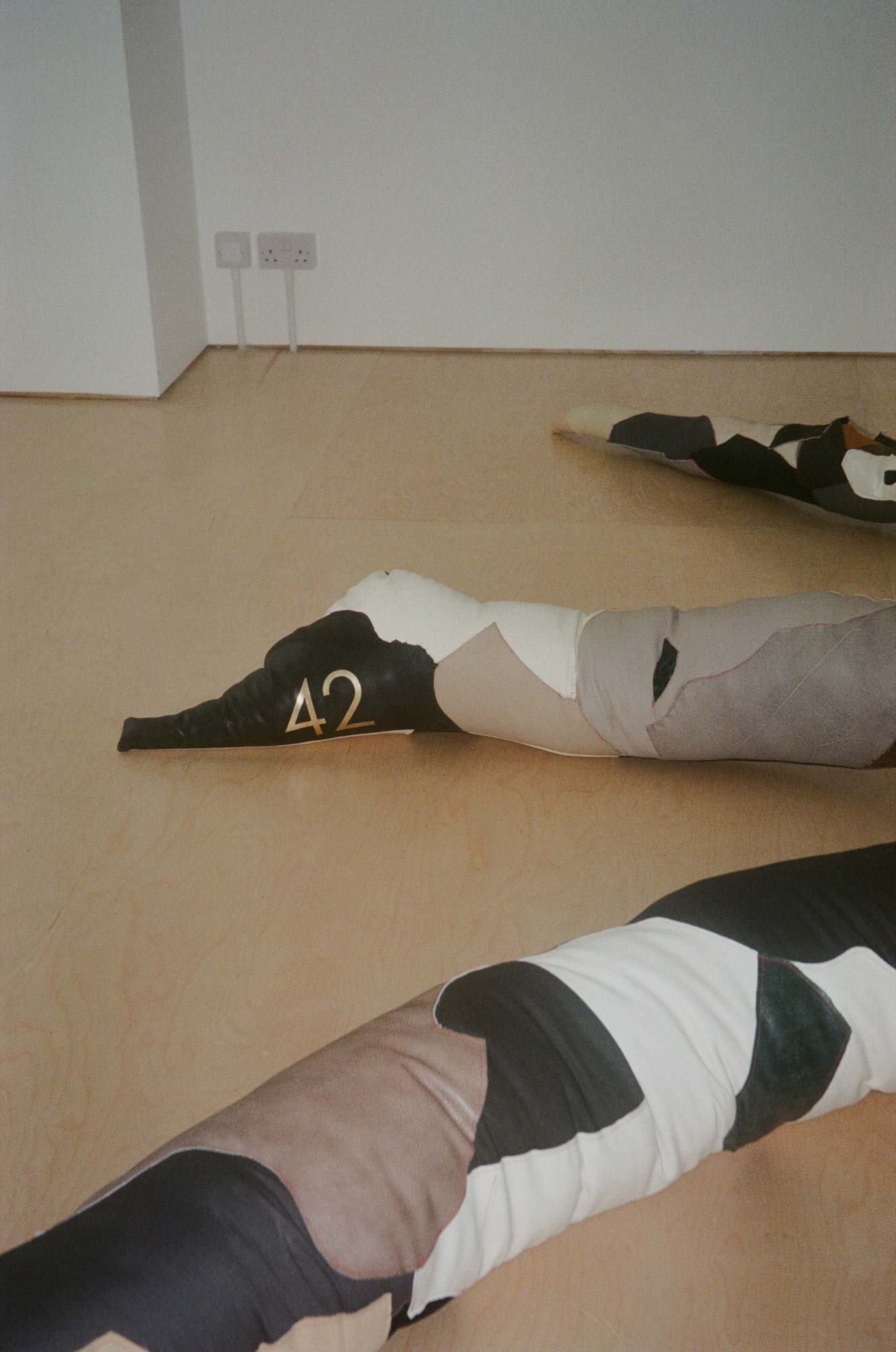

Grey Wielebinski’s monstrous amalgamation of the Sphinx and the Scorpion guards a space space which without itself would be empty. The creature becomes the physical guardian of itself and a metaphysical guardian of the manifold. It’s the metaphorical keeper of the balls, which simultaneously gives it all the power and none. The power to make us question gatekeeping in women’s football, for example. But the creature itself has no power. In its stitched-togetherness is it an empty vessel, a metaphor for what we want it to be.

Similar to the way that the stories of Gaia, Artemis and the Sphinx are told through men’s stories, is women’s football considered from the top down? The top being men’s football. The men are the keepers of the gate, they control the narrative – without them there would be no gate, or would there!? Gray’s creature takes the narrative away from everyone, interrogative of everything, and becoming itself the keeper of a multitude of gates both physical and metaphorical. In the process, the gates become neutral, of person or gender, and more specifically, the gender of creature, artist, audience, becomes unimportant. In the same amalgamation that created this creature the gendered view on football merges into one.

The keeper of the balls doesn’t care. All’s the same in front of its presence. It guards nothing, which is everything.

Lynn Seraina Battaglia, She Performs co-founder and curator.

Sources:

30.07.19

Words by She Performs

Related

Curatorial

Dark Air

Studio Visit