Fiontán Moran is Tate’s rising-star Assistant Curator. Major recent projects he has worked on at the museum include the solo exhibitions of artists Steve McQueen and Andy Warhol, as well as the acquisition of a monumental work by artist Cecilia Vicuña, “Quipu Womb”, (2017). Alongside this, Moran moonlights (and sometimes daylights) as a dancer and performer, and his choreography has taken place at venues including the legendary pub “The Glory” in Dalston and “Wysing Art Centre” in Cambridge. DATEAGLE ART spoke with Fiontán about a range of topics; from the ‘80s track Warm Leatherette (1978) to the importance of nightclubbing and queer venues; José Esteban Muñoz’s book Cruising Utopia; CAMPerVAN, the queer performance collective he belongs to, and his ongoing zine “Death Becomes Herr”. Watch out for Moran’s exciting and radical upcoming project, Set and Reset, focused around Trisha Brown, one of the founders of postmodern choreography and dance, who is known for her experimental and seemingly improvised performance, despite Moran’s declaration that “actually, every flick of the wrist… is carefully memorised.” Alongside archival material and films, the display will also feature collaborations with Candoco Dance Company and Rambert, a combination that will transform the museum into an intimate space of bodily movement.

Beginning with the beginning, was there a defining moment that brought you to contemporary art?

I enjoyed this question. There wasn’t a defining moment in relation to contemporary art, but definitely in relation to art in general. I didn’t really grow up going to museums or anything like that. The first time my dad’s friend took us to Tate Britain. We saw the typical Pre-Raphaelite paintings, and I remember being struck by Ophelia (1851–2). You know, very low-key dramatic! To be honest, because I grew up in London, my introduction to contemporary art really came through going to Tate Modern; that opened up a whole new world, and it also became a special space to go to without having to rely on friends. Later, while I was studying art history, I did a course on performance art, and, although it was historical, it brought me to some contemporary artists that utilise performance like Marina Abramović.

How did you get into curation? Do you remember the first show that you organised?

I didn’t necessarily think I wanted to be a curator – I didn’t actually know what a curator was! I knew I liked the idea of working in a museum. Initially, I wasn’t too sure what to do. I ended up doing some internships at Serpentine Gallery, Tate, and also at Sotheby’s. That helped me understand more about what the actual art world is. Because studying art history doesn’t necessarily prepare you for the reality of how the ecosystem that exists between artists, auction houses, galleries and museums fit together. Through that process, I started to become more interested in how you can tell different kinds of stories via exhibitions, but also through a museum’s collection. I interned at Tate during the show called Pop Life: Art in a Material World, which was a perfect fit for me, not just because the title references both Prince and Madonna, but also because it was an exhibition about how artists play with the idea of the art market, or with the idea of art as a commodity, something I was interested in. Also, the crossover between fine art and popular culture was something I had been interested in from a young age, having arrived at art via film or pop stars, and then discovering Andy Warhol, who is the gateway drug to all types of expression. So that exhibition was a special one. For instance, I got to hang Keith Haring’s t-shirts in the recreation of the Pop Shop.

Are there any particular curators – contemporary or historical – that you have found to be guiding forces in your career?

Yes, it was nice to think about this. Catherine Wood, Senior Curator of International Art (Performance) at Tate, and Stuart Comer, who was Curator of Film at Tate and is now at the MoMA, have always been very supportive, and great colleagues to bounce ideas off. Before I even worked at Tate, I always visited Stuart’s film programmes, which very often had a queer lens. For me, as someone who didn’t feel comfortable with my sexuality, it was a special kind of space to go to. In terms of historical figures, I’ve always been interested in artists who have curated shows. For instance, Sunil Gupta’s shows of lesbian photography, or even the fact that Frank O’Hara was a curator at MoMA, but is more known for his poetry, or Nan Goldin’s show, Witnesses, that she organised in relation to the AIDS epidemic. I found those figures really useful to consider in terms of how to create exhibitions, as opposed to thinking about this purely from a curatorial angle, or a traditional art-historical one. These are people who think about the world in which they’re living.

It seems that contemporary curation currently involves many different roles. I want to ask some general questions about your position as Assistant Curator at Tate. Firstly, how does an idea for an exhibition there typically come to fruition?

Exhibitions usually begin with a proposal from a curator, which is discussed and analysed by a wider team including the gallery Director. Many ideas come out of wider curatorial research into the gallery’s collection. It is a very collaborative process and shows are often organised alongside other institutions from all over the world. Tate’s exhibition schedule as a whole is also carefully considered and choreographed to ensure the organisation is telling a broad and diverse story of art history. The process of an exhibition being proposed and confirmed to its actual opening is a long one – it can last anything between three to five years, sometimes even six. I always say, in some respects, that you’re signing away your life when working on an exhibition; at least, because you’re working towards future deadlines that are very far away. However, that’s also a positive attribute, because it gives you time to work out complex ideas, as well as to handle the thorny loan negotiations involved!

And what would a typical week as an Assistant Curator look like?

Really, I know it’s a cliché, but it is extremely varied. I have described working as an Assistant Curator as being like a bridge or an octopus as you are meant to be the conduit for various departments to know what’s going on – from marketing to conservation and installation. It varies depending on what phase of a project you are at. If you’re at the research stage, you’re spending most of the time with your curator, and sometimes with the tour managers. On a day-to-day basis, it’s a desk-based job. You’re not really in the galleries as much as you’d like to be; you’re only really in there if you’re installing something. It’s quite varied, and it involves a combination of meetings, research, and a lot of emails, but also really interesting conversations.

Are there any elements of curating that came as a surprise to you?

Even though I’ve worked in a museum for years, it still surprises me how certain decisions have to be checked by lots of different people. I always used to say, as a joke, that if you want to move a chair at Tate you have to email ten people. But then I realised this was essential; that chair might be owned by someone, or another person might be using it for an event, or it might be set up there for a reason. In terms of the actual curation, it’s also the possibility of being able to develop projects that actually have a personal significance. Initially, I was struck that there could be an exhibition that deals with queer identity, or a project where you could bring in your own lived experience, and that it would be beneficial to the museum in some respects. Because I came from a traditional Art History background where it was sometimes regarded as dangerous to bring your own lived experience into your work, so that’s been a lovely surprise! I think it’s also important to acknowledge that, as human beings with different kinds of stories, we inevitably bring those with us.

In 2016, you wrote for Various Small Fires that “with the advent of social media and tools such as Photoshop, the original strain and effort that people encounter in their lives can be hidden, so that truth only resides in the (altered) image presented to the world – performing our ideal selves for a camera, hoping to escape from the muddy gutter of the street and up towards the stars.”Do you believe our relationship with the camera has changed since the induced, unprecedented global lockdowns?

I think everyone’s relationship with screens has definitely and inevitably changed, especially during lockdown. I don’t know about the camera. It’s always changing, even the way that social media continues to adapt and evolve, and how different platforms become increasingly popular. I think that the relationship with the camera on TikTok, for instance, is very different to that on Instagram. It is far more actively physical and performative, and it involves acting and editing as well. I don’t know how much lockdown affected these broader changes, although I know that for some people, lockdown conditions made them feel differently about their gender identity, in a weird way because they weren’t being seen by others as frequently. So, they had the chance to develop different kinds of relationships with their body, perhaps, or were able to embrace things that they maybe had chosen to ignore or hadn’t had the time to think about. I find it interesting that a lot of people, particularly younger ones, exhibit their lives via photography, and that this documentation can inform how they internally feel. This is something I have been thinking about a lot recently. In contrast, I also think – and maybe it’s just the clubs I’m going to – that people don’t take photos in them as much as they used to. I could be wrong, though.

Performance is a massive passion of yours; from working on the landmark show ‘Performing for the Camera’ at Tate in 2016, to only just recently introducing Derek Jarman’s ‘Sebastiane’ (1976) with a dance instruction piece based upon Lindsay Kemp’s choreography for the film at the event ‘24 HRS BENT: JARMAN IN 24 ACTS’, and recently performing at Wysing Art Centre. Can you tell me about the ethos and practices of CAMPerVAN, the queer performance collective in which you belong?

Yes, CAMPerVAN was a project initiated by the multitalented Samuel Douek. He’s now a film director, but for his MA architecture programme, he was investigating the closure of so many queer spaces like The Joiners Arms, Nelson’s Head and The George and Dragon, and began asking “What makes the space queer?” or “How can you make a space that can avoid being affected by gentrification?”. He had this idea – I never asked him properly, but I’m pretty sure it must have partly come from films like The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, and Hedwig and the Angry Inch – of a travelling queer space. So, he bought a caravan, and literally cut into one side and hinged it to create a folding stage affixed with light bulbs. Then he asked me and my friend Zoë Marden, an artist and curator, if we could perform for his degree show. We did, and then it naturally evolved into producing different events across London. Also, we did a European tour in 2017 where we went to six cities in eleven days and performed in each of those places. For me, it was a great project, because it emerged naturally. It was a testament to our friendships, but also how queer spaces have been spaces where we each explored our identities and formed bonds with like-minded people. Being part of a project that is finding ways to bring queer performance to different audiences was fascinating. Because it’s a caravan, it takes place outside, so people walking past will maybe see a drag performance or poetry readings, or panel discussions without necessarily having a choice in the matter. It also made me think about how, when I was younger, going into a gay bar was actually quite nerve-wracking, so I liked the fact that this kind of space existed in the open while also providing an opportunity for me to do my campy performances.

The continued closure of nightlife is one of the saddest consequences of the pandemic, particular for queer communities who rely on these safe spaces that are becoming increasingly rare in urban centres. Have you observed a queer art and nightlife scene renaissance now that venues can reopen?

I think it was probably happening before the pandemic. The closure of many queer spaces happened in 2016–17. Since then, you started to see a lot more queer nights, at otherwise normally straight venues. Metropolis, a strip club in Cambridge Heath, hosted quite a lot of queer nights, because they ended up getting more punters. The resurgence of DIY raves and the techno scene has also meant that the idea of having an exclusively gay or queer venue, I think, has changed. It’s probably too soon to speculate whether there will be a renaissance just yet, because we’ve only just been able to have club nights again. But I think places like Adonis, which takes place at The Cause, and a few other nights, suggest that there is a new energy of creative club nightlife that I’m hoping will continue and develop. Also, we need to keep supporting little queer pubs and cafes because they are really essential spaces. I don’t think everyone wants to stay out all night in a big warehouse, as much as it’s enjoyable for some. It’s also important to be in queer spaces that are more intimate.

Named after the cult classic film featuring Meryl Streep from 1992, you also founded a zine titled Death Becomes Herr. The Tumblr account features some hilariously camp imagery. What was your ambition for the zine?

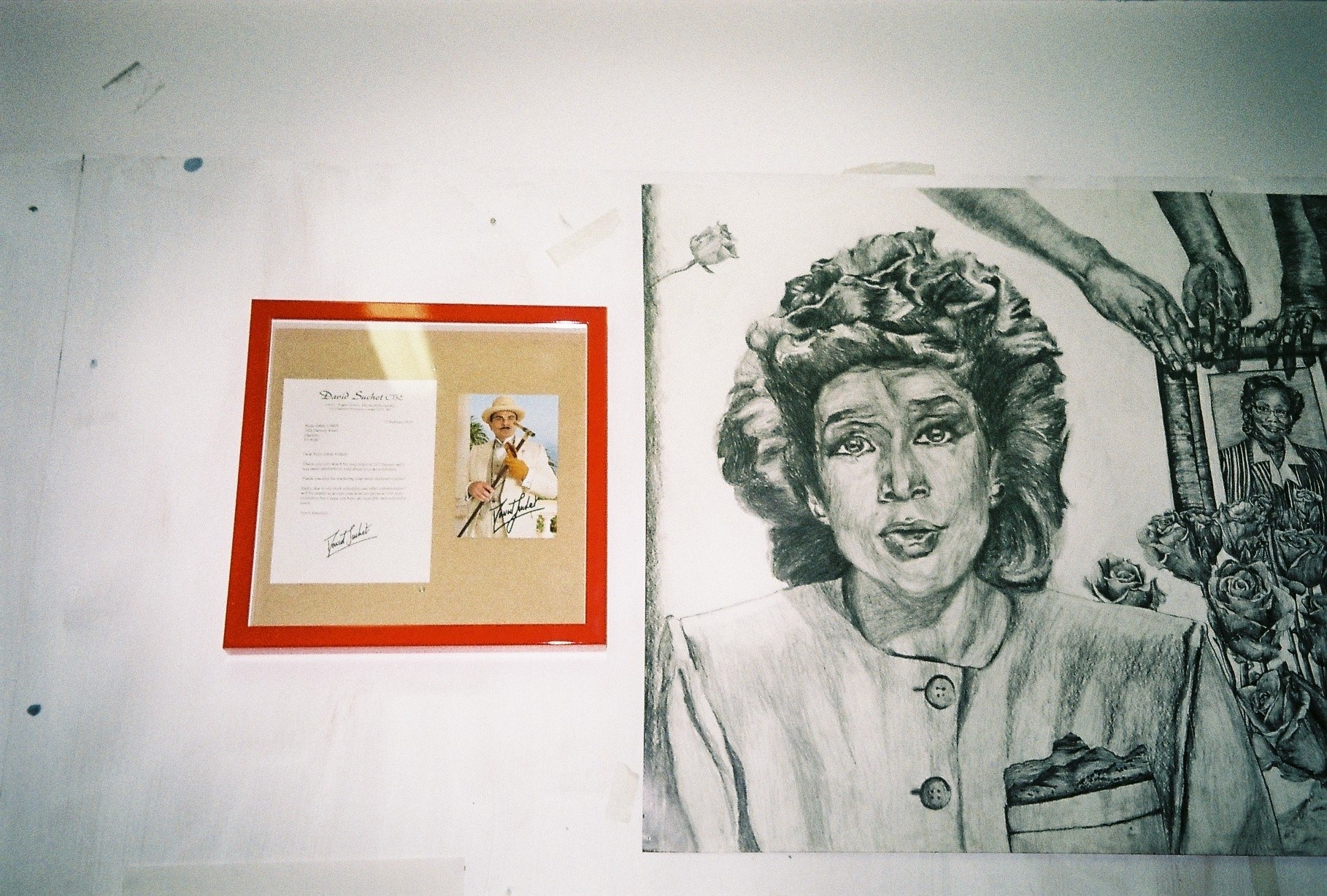

Death Becomes Herr is a kind of never-ending devil at the back of my mind because I’ve only published two issues. I always mention it in any biography that I write as a way to force myself to keep doing it, because it’s really just an excuse to throw all the art and cultural histories that I come across into one place and collaborate with friends. My original idea was to depart from the notion of a magazine being this kind of fractured entity, where you have an editor’s letter, and all these disparate contributions. Instead, I like the idea that a magazine could be a chronicle of one person’s day. For instance, a fashion shoot would become a scene of someone getting ready in the morning, and then the feature on Carolee Schneemann would be a phone call at work, and an interview would be after bumping into someone at lunch etc. It all comes from my love of magazines and zines while growing up, and was a way for me to experiment with creative writing, interviewing people that I admire and making collages. It’s an ongoing project. I actually have had a third issue ready for years. It’s a running joke with my friends, but it’s still in storage!

Last year, you worked on a major retrospective of Andy Warhol’s work in the UK. What was the biggest revelation you came across in the research planning of the exhibition, or the most unexpected reaction to the show?

There were two things. It’s not unexpected, but one thing to note is the challenge that you face when you do an Andy Warhol solo exhibition. Unlike almost any other artist, you work on a Warhol exhibition with an awareness that the public has certain expectations. They know far more about Warhol’s artworks than they would of any other artist. I think they would expect to see a Campbell’s soup can, Marilyn, and, if they’re really big Warhol fans, they might also expect a Screen Test. Whereas with another artist, they might know their name, but they probably would not be able to name five of their artworks, perhaps. So there’s this challenge of trying to give people what they want, and include Warhol’s greatest hits, but then at the same time wanting to bring to the surface the lesser-known elements, which I inevitably found most interesting. So, while I already knew about the Ladies and Gentlemen series of paintings of drag queens and trans women, I didn’t know about the backstory of how those paintings came to be; the fact that none of the sitters were people Warhol personally knew. So even though he had a history of collaborating and representing queer people, mainly via his film work, the sitters in Ladies and Gentlemen were people that were found by Warhol’s friends, because it was a commissioned project. I thought it was a really useful body of work, partly because it’s lesser-known, and also because it’s one of his biggest series, where he uses painting in a very different way. Also, it brings to the forefront questions surrounding the relationship between an artist or a sitter – the dynamic of “Who holds the power?” On top of that, there’s nothing known about some of the people that were depicted. So, the work also signals the historical lack of representation of trans people, and the difficult lives that they may have led, while also indicating that there was this other queer scene in New York very separate from the more glitzy Warhol scene, especially in the 70s. On top of that, I also just loved all the kinds of random things Warhol did. For instance, for his Raid the Icebox exhibition, where he was asked to curate Rhode Island School’s collection of objects, Warhol just decided to replicate the storage setup that they had, which was very bad. So, he kept the paintings propped up with sandbags, with one of them lying on their side. He also got them to exhibit all of their collection of chairs and rugs, stacked on top of each other. It was a real reflection of his own collecting habits; he was a massive hoarder and loved to collect many different iterations of similar objects. This relates to my interest in artists who have curated exhibitions. Although for Warhol, as is typical of his approach to many things, his attitude towards curating was just to have an idea and then push it to the very extreme.

From my perspective, curators are magpies for spotting elements of culture deserving a larger spotlight or further intellectual scrutiny. What are you currently thinking about? Can you give DATEAGLE ART any recommendations?

I don’t know about recommendations. I’ve had a long-standing interest in performance, especially in dance histories. So I’ve been thinking a lot about how dance is represented in the museum, something that Catherine Wood has done an impressive amount of work on by most notably staging the Musée de la danse project with Boris Charmatz, where they transformed Tate Modern into a dance museum. But I have also always been interested in the relationship between dance and performance and the idea of a ‘history of art’. I always remember reading this essay, as part of my performance art course, which spoke about this musical tradition where performers would wear costumes made from newspapers, so that the text would wrap around the body, and how this could be an influence on Picasso’s collages, where he would truncate words from newspapers. I’m thinking about all the different kinds of live spaces, and how they inform the history of modernism and contemporary art. Now it’s perhaps more common, with many artists interested in bringing club culture or popular culture into their work; it’s far more porous. It’s important to think about early histories and times when there was a lot of change, like the mass unemployment and recession in the 70s and 80s – how did artists respond to that? It’s interesting to think about communities that haven’t been represented justly, and people with different kinds of abilities. In light of this, there’s great work being done in terms of the visibility and the representation of bodies that are non-normative, from various perspectives. I don’t like it to be necessarily seen as a magpie kind of mentality, at least for me. It comes organically from research that academics and activists are doing, through conversations and collaborations.

Outside of Tate, where do you find inspiration and hope?

Firstly, friends. Secondly, queer clubs. When you see people’s creativity – the amount of time, energy and effort that goes into their looks, and the way people lose themselves in queer club spaces, that is something I’ve loved and found inspiring from my young days. I think nature has become a renewed place of inspiration for a lot of people during lockdown, because of its unique temporality, which is completely oblivious to the manic pace that a lot of us are living at.

Can you give DATEAGLE ART’s readers a preview of any forthcoming projects you are working on?

Yes! I’m working on a display of Trisha Brown, who was a choreographer and dancer, titled “Set and Reset”, with Catherine Wood and assistant curator Tamsin Hong. It’s seen as one of Trisha Brown’s most significant works and also as one of the most important works in the history of postmodern dance. The stage set and costumes were made by Robert Rauschenberg, and the score by Laurie Anderson. So, it’s a really fantastic example of major artists working together. The display will include the Rauschenberg stage-set, video of the performance, and videos of Brown rehearsing and working out the choreography in her studio. When you watch the piece, the choreography features such a fluid sense of movement that some people might assume it’s improvised on the spot. But actually, while the piece was developed through processes of improvisation, every movement, every flick of the wrist, for instance, is carefully memorised. That’s where the “Set and Reset” idea comes in. I’ve always thought that showing the rehearsal videos is the equivalent of showing a Cézanne sketch next to a Cézanne painting. I think they’re an interesting way to demonstrate the work that goes into learning a dance, but also how you can get a lot out of that kind of material that is very different from the final performance. In March, Rambert, a London-based dance company that has been licensed by Trisha Brown, will do six performances over a weekend. The following week, Candoco Dance Company, a dance company that works with dancers of different abilities, will do their version of “Set and Reset”, called “Set and Reset/Reset”, which is something they’ve had in their programme for 10 years and was devised by a former Trisha Brown dancer with Trisha Brown’s approval. So, it’s also about how dance is an art form that is dependent on bodily transmission; taught from body to body. So, in terms of the space of the museum – how a museum is thought of as a place of preservation – it sets up an interesting question. Then we’re hoping to do monthly lecture performances with the dancers, where they’ll talk in the gallery space, explaining the process of learning the choreography. It’s a project with many different angles. Also, I am working with Michael Wellen on Latin American acquisitions at the Tate. So I will continue working on Latin American artists, and also on the forthcoming Turbine Hall Commission, which is yet to be announced. Then I’m also hoping to do more performances. And finish Death Becomes Herr!

Your mention of Trisha Brown’s stages reminded me of the chapter on stages by Jose Esteban Muñoz in Cruising Utopia, where he describes stages as sites of an ongoing performance of utopia. He looks at the potentiality of histories that are yet to come; performance and improvisation as futurity. It includes really beautiful images of empty stages by Kevin McCarty.

I know! I also found it really surprising that those photos are really hard to find online, at least when I’ve looked around. They’re not that visible, considering they’re in this heavily referenced book. I really loved that chapter. Connected to this, I worked on a project called Charming for the Revolution: A Congress for Gender Talents and Wildness in 2012 that Stuart Comer co-curated with Electra. We showed, for the first time in the UK, Wu Tsang’s Wildness film from 2012, which was a docu-fantasy film that chronicles a night that Wu held called “Wildness” in Los Angeles. The work conjectures about how you can have a night that caters towards a community that you’re part of, and how you keep that going. How do you try to support the lives of people in those spaces? I think that chapter of Cruising Utopia, and a work by Rosie Hastings and Hannah Quinlan’s titled UK Gay Bar Directory (2015–16), touch on this thinking about queer spaces, chronicling them, but also reflecting on what they offer.

Yes, because there’s also an interview between David Velasco and Jack Pierson on the Artforum website, from earlier this year, discussing Pierson’s literal, physical stage, which he built as an artwork that slots into the corner of a room, consisting of a black plant with tinsel falling behind it, yet it’s empty. I was thinking about that, and Esteban Muñoz, and also what you’ve been speaking about. It might be quite an interesting exhibition, actually, to consider looking at stages as sites of queer potential.

Maybe we can do a show together! When I was recently at Cabinet Gallery, they had Wu Tsang’s gold shimmering curtain outside (conquistado, 2019). I like to think it’s a permanent installation; it was in her Gropius Bau exhibition as well, just this singular gold curtain. I guess it points back to the CAMPerVAN idea of what makes a space queer. Although, ironically, for CAMPerVAN, Samuel Doueck didn’t want to do anything glittery or pink, because, for him, a queer space was actually defined by the people that go there and the services it offers – a variety of entertainment, community and family.

And lastly, as we move into what has been named by many as the ‘new normal’, do you have any dreams for the art world as we move forward?

When you say the ‘new normal’ it reminds me of Daniel Miller’s project ‘The Normal‘ and the song he did: Warm Leatherette (1978)… An 80s reference! Well, I hope that the art world holds on to the many claims or statements made over the last year in terms of solidarity with different communities, and working towards racial and gender equality. But also, I hope that more spaces are made for those conversations to be held and heard, and then for actions to take place. Also, as part of that, I think nurturing artists and art workers in that process, and helping those conversations to take place, is also important. Another thing which seems to be on a lot of people’s minds is questioning the relentless speed at which a large part of the art world tends to function. I mean, sometimes that is really great because it means that things get done and some projects need that energy. But it is also important to think about how you can slow things down and create a space for people who need that time to work out their ideas, or to connect. If you’re always striding toward some impossible goal on the horizon, you can sometimes forget to connect with those by your side.

06.01.2022

Words by Laurie Barron

Related

Interview