Coming to terms with the current predicament of gender.

“The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” – F. Scott Fitzgerald

The term “male gaze” was first coined by film critic, Laura Mulvey in her essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema in 1975, where she boldly argued that the “gaze is property of one gender” and that the notion of a “female gaze” exists only as “a mere cross-identification with masculinity”. The male gaze is generally seen to be the act of depicting women and the world, via visual arts and literature, from a masculine heterosexual perspective that presents and represents women as sexual objects of pleasure for the male viewer. The male gaze directly implicates three different perspectives within any given image: that of i) the creator of the work ii) those of the characters within the representation and iii) that of the spectator. At its most extreme and destructive, the male gaze can be comparable to a form of Freudian scopophilia, whereby sexual pleasure is derived from observing the passive female as purely a sexual object.

The late, great John Berger popularized and expanded on the idea, and in turn made the notion of a “male gaze” mainstream in his iconic, Ways of Seeing: “According to usage and conventions which are at last being questioned but have by no means been overcome—men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Berger was rightly responding to the countless images we find in Renaissance artwork specifically, which often posited women as objects of desire for male artists and viewers to visually consume- a form of (religiously sanctioned) soft-core pornography. The women in such paintings lack agency and that’s why they can cause discomfort, when viewed by our generation.

The idea of studying art history or visual theory nowadays without accommodating the presence and proliferation of “male gaze” imagery that has flooded the visual field is practically unthinkable- to dismiss the notion is to miss the point completely and to glaze over the obvious disparities in depiction between the sexes over the ages. When I was studying, the term male gaze was a powerful weapon and tool to criticize a man’s artistic output, working most effectively with pre-20th century art (work created prior to the Women’s Liberation Movement, more specifically), but could actually be applied (even if sloppily) to any man’s artwork, even if it didn’t depict a woman. I’d haphazardly litter my essays with the term, using it as a means to vent my angry feminist sensibilities and to avenge the undervalued women found within such images. But the state of gender relations has seismically progressed since the 70s and the output of second-wave feminist theory in which this terminology was originally borne out of; even though we still apply the term in the same way- and to artworks made in our markedly more progressive, contemporary culture.

We now live in a world where men and women are more equal than they have ever been. Fact. A world that has become so fixated on not causing offence to those that were previously overlooked or subjugated, that we’ve become obsessed with creating increasingly specific definitions to accommodate certain social positions and perspectives. My feeling is that quite often this engenders separatism between the sexes (emphasising difference) rather than unification. If you speak to men about modern feminism, even those who are entirely for equality, feel threatened by the language utilised in feminist rhetoric. Male artists are painfully aware of the privileged position they’ve held over the centuries; many are ashamed of it and wish to sensitively shed their silver spoon- and are still being hurled the same denunciative critique. In contrast, female artists are currently enjoying their newfound recognition for possessing a vital perspective and recent reclamation of space within the art world. It’s been a long time coming. And quite rightly, women should take some time to bask in the sunlight of appreciation, but one must not forget that a woman’s vision is not a revolutionary act in itself, a female gaze has always existed and it comes with its own deductive qualities and its own set of projections.

When I interviewed Charlotte Colbert earlier this year I was struck by her honesty when she said, “I don’t know whether the female gaze is any less imprisoning than a male gaze, because there’s always a form of objectification at play, just by looking at someone.” In a sense, this notion sparked my desire to write this piece; to open up an honest dialogue about the nature of gendered art criticism and gazes- drawing upon conversations I’ve had with young, contemporary artists practicing today.

Photographer Alice Joiner’s work is intimately engaged with her female gaze and came to the medium as a result of a self-documentation process during her recovery from anorexia. For Joiner, the issues associated with gendered gazes are due to ownership and awareness, “I think that the notion of the ‘female gaze’ highlights a sense of ownership of the female standpoint which is crucial to finding equilibrium within our society. I do think that gender is fluid, but considering the nature of art and artists consistently referencing art history, it is imperative to specify and take ownership and responsibility for our work and the topics we are sharing. My work for example is about women, female sexuality and honouring strength, fragility and empowerment and the female gaze within this context underlines a sense of strength.”

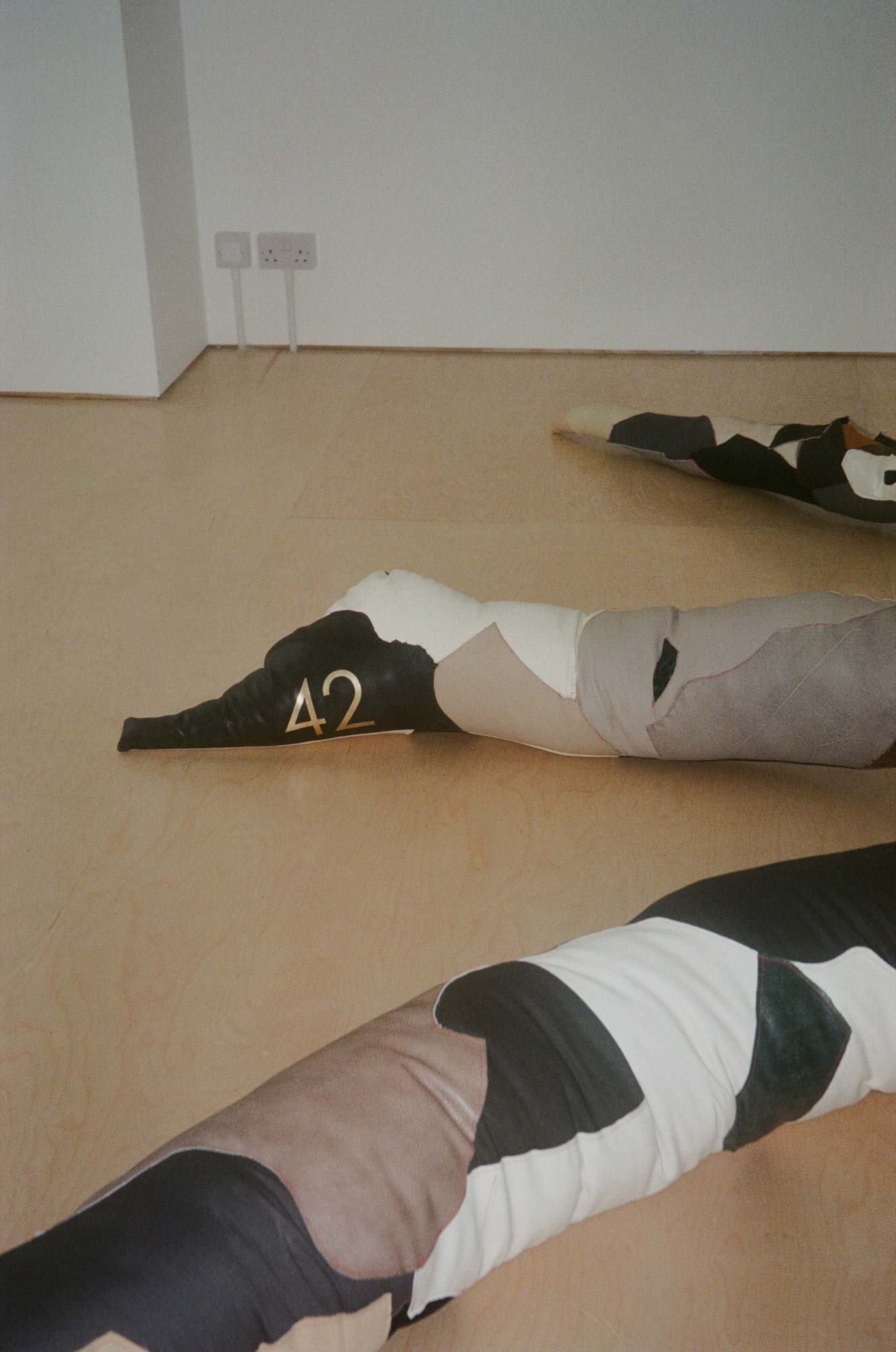

Similarly, painter and printmaker Venetia Berry’s work also actively takes on the staid notion of a “male gaze” and gives prominence to a more sensitive “female gaze” by purposefully reimagining the aesthetics associated with the female nude. I asked her how she’d feel if a viewer discerned a clear female gaze within her work: “I would be delighted. One of the main aims of my work is to reverse the age-old ‘male gaze’, and allow women to reclaim their gaze. I want to desexualise the female nude in art, celebrating women of all shapes and sizes, rejecting the patriarchal expectations of women in society today.” Berry suggested that the notion of gendered gazes within art and criticism nowadays still has its place, “as it educates us, as to where the view is coming from, and allows us to have a guess at their life experience. However, I think it is important not to generalise or prejudge individuals, particularly with the male gaze, which is often portrayed in a damning light.”

In a similarly sympathetic way, painter Kate Dunn suggested that, “there is a worry that by adding the notion of the ‘female gaze’ to a piece of work, it becomes elevated without question, equally, the opposite to the notion of ‘male gaze’ (when paired with a male’s work) and it then being disregarded. Ultimately, I am not against gendered criticism, but attempt to question its relevance and intention.” Kate has recently moved away from portraiture/figural depictions in her artwork, and has been exploring abstraction and the tactile manifestations of paint and materials. Interestingly, she explained how nowadays notions of gender only surface in her work in abstracted terms too, “There have been days where I have specifically set out to make a ‘feminine’ painting, involving notions toward a ‘feminine’ aesthetic. But really all that means is that I am using colours that we associate more with the feminine than the masculine. The marks themselves I believe have no gender.” This reminds me of how Clement Greenberg attempted to frame formalist pursuits and abstract expressionism- the work of Pollock and Rothko and the gestures they made with their brushes- as being, somehow, peculiarly masculine, and aggressively so. This notion feels regressive nowadays too; it would be seen as a huge shortcoming to suggest that a woman’s hand inherently rendered a more ‘sensitive’ or ‘soft’ touch.

When I spoke to Billy Fraser about the nature of such criticism within arts education he told me how being one of the only white heterosexual male in his year meant he was regularly thrown the ‘male gaze’ critique, despite not always depicting the human figure in his work. In this sense, the consideration of such theory plays a part in his creative process, “it would be ignorant to assume the artist could make works outside of his or her own condition. When making an artwork you have to be consciously aware of the art context and history in which the artwork will exist. Male or female, you have to consider the connotations and nuances of something so subjective… it’s a creative mind-field the artist has to tiptoe through.”

Painter Leo Arnold explained how for him, the notion of gendered gazes is a systematically inscribed issue and in this sense the artist shouldn’t necessarily attempt to negotiate it, “Politically speaking I don’t have much of a problem with the notion of a gendered gaze. The political problem as I see it is in ubiquity. The male gaze is not innately wrong; I see nothing wrong with a heterosexual man expressing his sexual desire toward women for example. The problem is that this angle is ubiquitous and in its ubiquity has oppressive effects (constraining paradigms of beauty etc.). We just need a diverse representation of artists’ expressions of sexual desire not mainly heterosexual males. This is more a systemic problem than an artistic one to me.”

This seems to me to be the key point, with either male gazes or female gazes, the importance is diversity in representation of a wide-range of perceptions. A truly intersectional gaze would attempt to dismantle the inherent power structures by accommodating an array of narratives or perceptions, rather than placing some on a pedestal due to their gender origin and denigrating others on the same grounds. My fear with the growing trend in all-female art shows is that, if a female’s work isn’t in dialogue with a variety of artist’s work then it might be criticised as existing in a vacuum or echo chamber; i.e an insular feminist orientated bubble that isn’t open to external forces. Having said that, I have been to some really beautiful all-female art shows and I think they’re integral to the precise times we’re living in where visibility is accelerating progression, but I don’t believe them to be the future. In the sense that nowadays there would be mass outrage if a gallery announced a purposefully all-male line up- for me progression means equanimity in the truest sense- and equal representation for all. Opening up awareness through multiplicity.

We all personally have to come to terms with the current predicament of gender and functioning purely in the arena of definitions and inscribed meaning is a painful burden to bear. By unilaterally emphasising difference and insisting that the male and female gaze cannot be reconciled, then what real hope is there for achieving true equality? Subjectively the art that has truly moved me is the type of work that aspires to a universal gaze or awakens a greater understanding of the multi-faceted nature of humanity. Great art connects and enlightens by collapsing superstructural boundaries through the expression of a pure communion with direct experience. Whichever gender it is derivative from, beautiful and moving art will quiet down outside noise and bring one to a place of greater understanding and sensitivity- work that takes the female experience as its cue will ultimately enlighten the viewer as to how it might feel to be a woman- essentially obliterating the biological and rhetorical parameters placed upon gender.

Painter Maria Kreyn, whose work deals with modernising mythological constructs and archetypes, expressed the idea perfectly: “That’s what’s so interesting about our current times, now as we ‘gender bend’ in our culture. Like how recently our language has become more rigid and precise, as we’re trying to figure out the complexities of gender, it would be interesting to attempt to look through different eyes. Not ‘male gaze’ or ‘female gaze’. I mean, imagine what that could feel like? Because I think we probably all have a plethora of views inscribed within ourselves to some extent, or at least, they can all be cultivated through empathy.”

Images of works in order of appearance: Charlotte Colbert, Alice Joiner, Venetia Berry, Kate Dunn, Billy Fraser, Leo Arnold, Maria Kreyn.

09.07.18

Words by Charlie Siddick

Related

Journal

In conversation with Rhino

Journal