Listen to your body, find your voice.

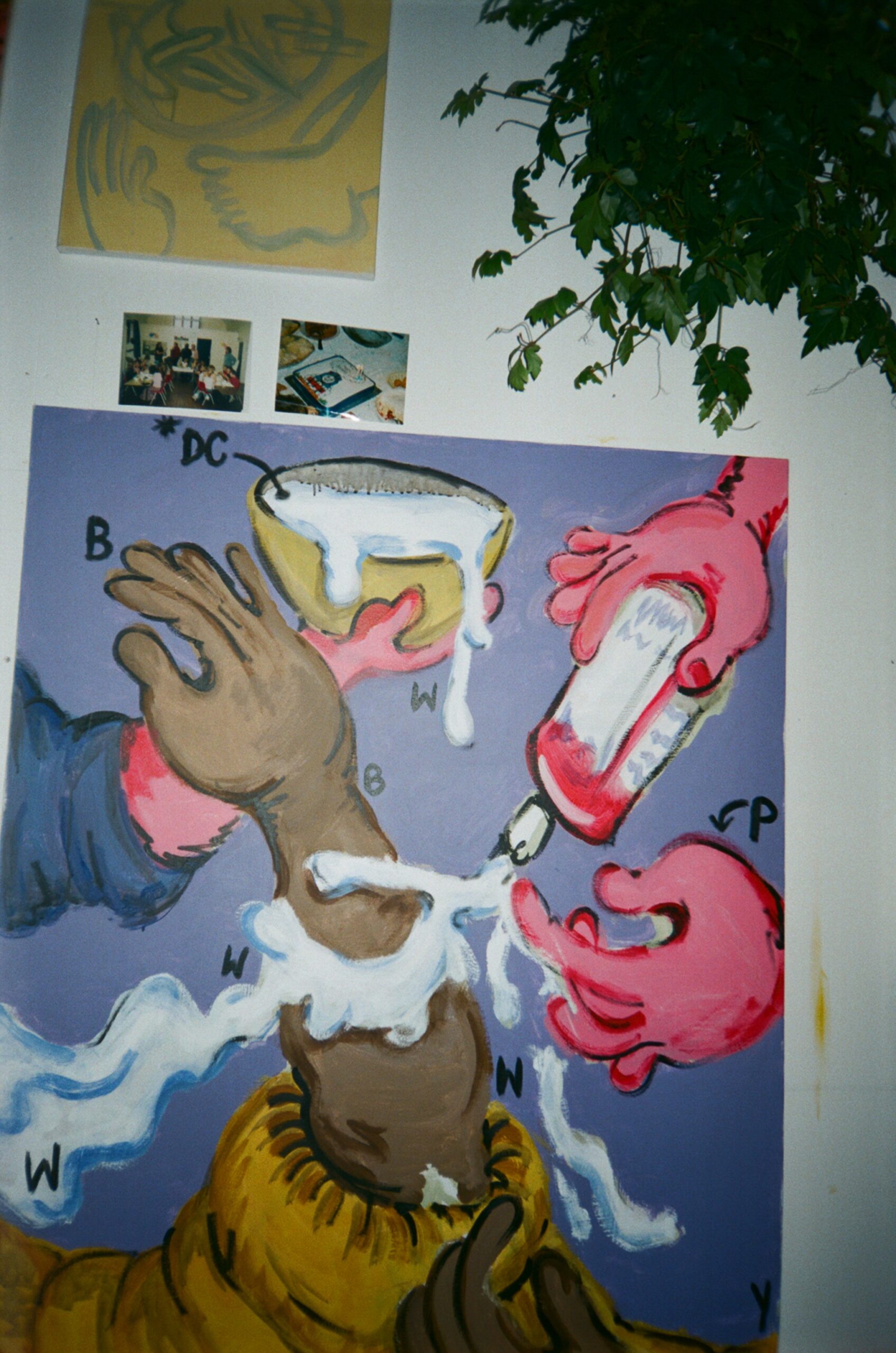

In a confluence of direct experiences, London based artist Adébayo Bolaji leads a fluid practice that looks inward to comment on the outward. Bolaji’s depiction of raw bodies provides an apt access point into this dissolution of boundaries. Their naked flesh embodies a metaphorical, spiritual interior, which organically emerges in an intuitive exploration of himself. Alternating between painting, performance and poetry, his work is an investigation of personal history and a form of psychoanalysis. His layered constructions, crafted from African textiles and found objects, address continual change through the lens of his Nigerian heritage and London upbringing. His process, which the artist describes as a dance and fight in unison, adheres to the mission of welcoming accidents without these being carelessly impulsive. Mediating chance and control, his artworks rise from signals and symbols that narrate greater stories of perception, strategy and subversion. I spoke to Bolaji about how these attributes come together through colours, gestures and textures, and how delegating with people and stumbling across mediums enables ideas to form.

BACKGROUND

Beginning your career as an actor with a training in law behind you, you have compared life before becoming an artist to “walking with a limp”. What first steps did you make to overcome this “limp” and transition to performance and art-making?

Firstly, I don’t really see a separation between performance and art-making, although I know we give ourselves distinctions so we can navigate the world better. It’s a good question because it infers intention and I think it’s important to say that I did intend to find out what this limp was. The limp was manifesting itself in the form of headaches and writing was a way to unleash frustration whenever I wasn’t acting. So, I wrote. I began trying to write lines of characters down because I made the assumption that it must mean I feel like writing a play since that is what I’d also do apart from acting. However, I was wrong. The headaches were so visceral that when I took pen to paper with the intent to actually explore them, I ended up drawing instead. It was very strange. But then, I would ignore the drawings and try to write. This battle, between writing and drawing, made my book look somewhat psychotic, basically scribbles everywhere.Thinking over this period of my life again, I realise that whenever we encounter things that are actually above intellect or are logic proof, you have to admit that you don’t know it all. And so, I literally prayed, asked, and cried… “what is going on with me?”. I believe that submitting to this act of not having the answer, actually allowed it to come through, which was: “Go and buy paint”. It was so simple and yet, somehow weirdly life-affirming. I was on tour acting when this all happened, so I couldn’t wait to get back to London and buy paint. I guess my body was saying that I needed an instrument, a medium that I could visually oversee and one that had an immediate connection to the world, which is why I always thought acting was the thing because it encompasses these rules to a point. It doesn’t do it completely because so many other factors are at play, i.e. the writer’s voice, the director’s voice, etc. Whereas this was everything else coming through me alone and then out again.

How did you employ what you had learned previously in your quest for complete artistic expression?

Acting and law offer great tools, such as asking the right questions. A lawyer has to do that, and an actor has to do it too when exploring text and character intention. In short, both schools offered tools to help me navigate my way through and somehow find harmony through all my experiences into this total art form of painting and more.

Do you see your Nigerian heritage and English upbringing as having provided a creative outlet for self-exploration? Do you engage in a healing transformation in unearthing the past through the present?

Everything, if understood, can provide some kind of creative outlet. I mean, my Nigerian culture is full of expression in so many forms, even from how an individual carries themselves, to clothing, food, rituals and faith. The same thing happens with my English upbringing. What I’d say is that having the benefit of two cultures provides an interesting mix. Almost like how a hip-hop artist mixes a classic soul beat with a modern-day melody and then raps on top of it. It’s like an audible collage. But I believe it also takes something else to simply recognise the wealth around us because we can be surrounded by things that we don’t even acknowledge. That I think is sad. In regards to a healing process, I was reflecting on this today. When we are young, like during childhood, we are arguably free from societal ideas. Then at some point, these impressions begin to build layers on us, and in turn, we start proverbially clothing ourselves with them too, creating some kind of person we think we should be so we can survive. If we are lucky, like in my headache experience, life and your own younger self will let you know they’re dying and that you need to get rid of these preconceived ideas to do what I call, “following the line” of your true idea. So you begin to strip all these layers off, or rather take off what is not needed and start adding true intended layers at the same time. It becomes a rebuild, or as you say, healing. Now, I do intentionally engage in the building of who I truly am. I think a good way to do that is to move consciously, being awake and not just existing.

I’m aware that you were fascinated by objectivity and subjectivity during your legal days, what other interests within jurisprudence have you brought forward into your works?

Context. In other words, change the frame and you’ll change the meaning. The painter and sculptor Marcel Duchamp spoke of it clearly, in that when you put the same object into a different environment, its meaning changes. He also spoke of the power of words, that they come with conditions and that they don’t always mean what we think they do. You might say, “Well that’s obvious.”, however, if it were so, a lot of the arguments that happen wouldn’t actually take place if we were always unequivocal and listened properly to the other person, right? When an artist really gets the context, they can have a lot of fun with how far they can stretch the truth and reality.

WORK

Having initially begun drawing whilst travelling between acting jobs, what role does this practice of untangling ideas play in your daily ritual?

A therapeutic one. Every day, I’ll untangle my mind this way, clear my head and hope to be surprised by something too. There’s also an inner connection that’s good for the brain and hand muscle, to stretch that muscle and not take it for granted.

You have cited your acting days as seminal in teaching you how to build a narrative through layers. Your paintings mirror this idea in form, as they are built up in coats of varying thicknesses. Does overlapping paint deepen the message that you want to transmit?

Good question. I think everything is an impression, texture, colour, line, everything. So whether I use it or not, it’s doing what it needs to do for a reason.

In your studio, you carry out a particular method of surrounding yourself with past works, as well as keeping your collection of materials visible. Do you find that this helps to weave together a united whole, as loose fragments encounter unexpected interactions?

Yes, it does. I have no shame in saying that I accept that everything is a potential impression and so, this gives me a focus in building whatever I need to. I also like the impression and attitude it gives me, like “here in this space, everything is allowed and everything is mine to do as I please, no rules unless I say so”, that sort of thing. Does this cause dialogues to arise between canvases? If needs be yes, it helps it. Like when I direct a play, like actors on stage, so somehow a through-line is being carefully constructed. Harmony, if you will.

How organic has your evolution from 2D to 3D been?

Very. It’s always been there, I just wanted to stay faithful to the timing and impulse and not to push it.

The bold and bright palette of your paintings contrasts with the earthy and raw tones of your sculptures. With a varied visual language, how does your approach differ between mediums, especially in the handling of readymades?

The first difference is, with sculptures I design first. I create a sort of template to build upon, and then, as I’m actually building the thing, I respond and improvise with the initial idea organically growing. It’s really like a dance and a fight at the same time, in a good way. Readymades also, I don’t like using that word, it’s too contrived for me now. I think it’s had its time. I just think everything is alive and living, they either speak to you or not. So, if I see an object that has something to say to me and I want to talk with it too, then we grow from that. Arguably, it’s not even ready-made because everything is always in evolution. But one says, “Aha, but it is already made then.”, yes, but again, context. I’m not approaching it like a readymade, I’m looking at what it can become rather than an absolute object. Words words words. I know.

Your method of constructing sculptures begins with a drawn plan from where you create a list of materials that your team of fabricators proceeds to search for. As you gather found rather than bought objects, how much do you embrace the unforeseen surprises embedded within these discoveries?

Massively, I welcome supposed accidents. Here’s the spiritual side of me talking now. To me, it’s already complete and we’re unravelling out into the thing. It’s fun, I want to be surprised. In fact, that’s why I also like writing the list and having someone else to actually go pick it up because then, at times, I go “You know what, I never thought it would look like that, let’s keep it.”. I’ve spent too much of my life trying to have all the answers and be in control. It’s so draining.

To what extent does your process combine chance and choice to determine the outcome of your works?

Wisdom to me is knowing that I don’t know everything, so what you call chance I welcome.

In reaction to a lack of visibility for people of colour, you have portrayed black female figures gazing directly at the viewer. Does this stance aim to characterise them as empowered, rather than sexualised? How else do you bestow agency onto them?

It does. Actually, once, a woman asked me why I paint the female this way and said that she wasn’t sure if I like women. Then she thought about what she said, as well as how I actually paint them and took back her statement. Yes, black is beautiful, so why not?

Depicting angular legs, disjointed torsos and floppy arms, how does the dynamism of your postures affect the energy and subsequently the mood of the image?

What the theatre taught me is the power of gesture and that even one being still with intent can move a whole crowd. So yes, these things affect the mood a lot. For example, you can create a story in your head about an individual simply by how they stand or walk into a room, right?

How does the flesh that you render become a gateway to discussions of the self? Does baring the raw body create a dialogue between the internal and external?

Good question, it goes right to the core. The individual. Bang. No interference. I like to get right to it. Haha.

You usually prefer to draw without reference, but in “Lady Works Machine”, a canvas commissioned by Ancestry UK, you responded to a photograph of munitions worker Miss Spize Hooker. What elements of this photograph compelled you to make a study of it? How much did her story inform the shifts between the original image and your portrait?

To keep it simple and honest; I just looked at the image and did not bring my biases. I ask myself, what is the image giving me, what does it want me to know and see, what questions do I get from it. I start with that and continue.

Considering your embellishments with traditional African textiles in your canvases, and given the rich cultural history of African Wax Print, what are you intending to express through fabric?

That I love the way it looks and feels. Isn’t this beautiful? It may have other inferences but, if it does it will lead me there, I don’t impose any ideology or political thought.

In religious contexts, garments hold connotations of status signalling and ritual. How does dressing your figures change the viewer’s perception of their persona?

Signals. We speak through them. So they are signalling something, leading the viewer somewhere. I’ll say that much.

With titles such as ‘The Priest’ and ‘Selah’, it is evident that your work articulates biblical chronicles. Is there an interplay between the duality of The Prophet, who speaks for God and The Priest, who speaks to God, and that of the artist, who is also communicating with an audience?

Ha. Yes, there is. This idea of medium and source, function and roles. Humans, or let me say, one, can be too arrogant to think of themselves too highly. I am breathing, I am part of something more. I am not the source.

Your sculpture “Trojan. 2020” references the classical story of the Trojan Horse. Intrigued by the perception, strategy and subversion embedded within this allegorical tale, what philosophical and metaphysical teaching did you aim to catalyse with this work?

I think I’m playing with signals and symbols again. Symbols such as Machiavelli’s ‘The Prince’ teaches us power can be used for evil or good. Branding, the marketer, these are all powerful tools of deception as in for deception, or again, for good. The great war books, such as ‘The Art Of War’, talk about strategy, gameplay, all these things.

FUTURE

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, you are developing choreography for a future film. Stating that “gestures are like statements”, how will you interact with dance as a form of protest? Do you perceive movement to be more effective a means of communication than painting, poetry or sculpture within the discussions surrounding race?

No, not more important. I just allow the idea to dictate the medium or way of expression. It knows what it wants. It’s good to listen.

Having compared moments from the COVID-19 pandemic to sacred periods of cessation that facilitate clarity, oneness and revitalisation, how have spiritual teachings impact the works featured in your upcoming show “The Power and The Pause” at BEERS London?

I think that real spirituality offers healthy reflection and not running away from things. I’ll say that much because I don’t even know myself. I’ve never been in a pandemic before! So I’m also curious to see how the works respond to this reality. That’s why it’s called ‘The Power and The Pause’. Power, because we have all sort of been brought to our knees and have had no choice but to pause.

14.04.2021

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Adébayo Bolaji

Interview