Shaped experiences and moulded worlds.

Musical, analytical and inquisitive, Yambe Tam is an artist fascinated both by individual experiences – of place, space and sound – and what lies beyond our earthly existence and human consciousness. At once fascinated with strict systems, and wholly open-minded towards new technologies and other lived modalities, her curiosity is boundless. And yet, the multiple mediums and perspectives she explores do not render her work paradoxical, but teeming with plurality. Her practice is guided, above all, by questions – whether about potential futures that await humankind, or sixth senses possessed by other species. The artworks strewn across her studio are not necessarily answers to these questions, but exploratory endeavours to translate these abstracted inquiries into physical objects and sensory experiences. Rather than work within the framework of what we know, Yambe is driven by existential and epistemological lacunae and, whether through wormhole sculptures or hypnotically chromatic paintings, lures us into worlds hitherto unknown.

BACKGROUND

You were raised in the expansive outdoors of the American Midwest, and now work in a studio in East London. Do you find this change in environment and, in turn, lived experiences, informs or affects your work?

When I was growing up, like many children I dreamed of the excitement of living in a big city, being in a centre of innovation, activity, and human achievement. Now that I’m older and have been living in urban environments since I was 18, I have this yearning for nature – not just parks and gardens, but the wild, untamed outdoors. In my work I try to reconcile these two halves of myself, which I think is part of what it is to be human in the twenty-first century – to be part of the natural world as a living thing, and yet separated from it by our own hand.

Did you find that studying in the UK, at the Royal College of Art, led to any significant changes in your practice, process or person?

There was definitely something of a transformation within my person and practice, which was difficult but necessary. I feel a lot more engaged and connected here, which is very fulfilling. A significant part of that resulted from being exposed to a more rigorous conversation happening around art, design, science, philosophy, and other disciplines. Because there was an audience who understood and was interested in the topics I wanted to talk about, like the intersection of art and science, I felt free to fully pursue these interests, as well as explore different ways of working.

I spotted a keyboard in the corner of your studio, and you mentioned that you were a very musical child. How do music and sound inform your practice?

Music was a huge part of my life. I started playing piano at the age of five, then later clarinet and violin. I was that kid always going to private lessons or after school and weekend rehearsals for band and orchestra. I never practised enough to make a serious career out of it, but I had a good sense of musicality that I only recently started to bring into my studio practice. The effect of music on the human brain is incredibly immediate and intimate. You feel the emotional impact in your body almost instantaneously and I’m interested in the ways my work can do this too. I started collaborating with an experimental musician, Henry Toh, this past year who helped devise an electronic system that vibrates my sculptures at their resonant frequencies. It’s actually very similar to how singing bowls produce sound, which is quite appropriate as it invokes connotations with sound healing. We experimented with different compositions but ultimately settled on something very minimalist and ambient. I wanted it to feel quietly spiritual, and was inspired by Zen Buddhist chanting, the liturgy of the hours, as well as John Tavener’s Funeral Canticle. The result doesn’t establish any kind of hierarchy between sound and object but rather adds another textural layer to it.

WORK

You mentioned that your brother supported with the mathematical arithmetic behind some of your work, and you are currently developing a VR project within a small collective of creatives. Would I be right in concluding that collaboration is important to your practice?

It’s something I really enjoy after having been a shut-in painter for so long, both for the fact that I’ve made some great friends along the way, and the fact that there’s a more diverse range of contribution. I’m always happily surprised by what other people bring to projects we’re collaborating on – it’s this diversity of approaches and ideas that keeps things fresh and interesting.

After initially starting with a greater focus on painting, you then came to experiment increasingly with sculpture. What provoked this switch to the three-dimensional?

I realised I was more interested in shaping an experience than image-making – not that the two are mutually exclusive, but I felt there were so many more possibilities when I expanded my reach beyond the 2D plane. Also I realised halfway through RCA that I had been thinking like a sculptor for years in terms of materials, space, and dimensionality, but trying to translate that into painting. It felt so much more natural once I stopped confining myself to the wall. As I got older I also became more accepting of change and uncertainty, so I was able to make this shift in my practice as well.

Sensory and subconscious experiences, such as light, colour, and sound, are prominent within your work. How do you navigate the limitations of working with a physical medium to explore the ephemeral and intangible?

For me, what connects them is the experience. So for example, I connect the idea of being sucked into a black hole with real-life experiences I’ve had like standing waist-deep in the ocean on a moonless night, of spiritual surrender, sublimation, which all refer back to being swallowed into a physical and existential void. And then I try to convey that in my work. It’s a process of experimentation, which is maybe why I work in so many different formats like painting, sculpture, immersive experience, as I end up trying again and again to get closer to the initial feeling.

The range of mediums you work with spans neon, rope, jesmonite and many besides. Do specific mediums serve as your departure point, or do you start with an idea and then seek the materials that best bring it to life?

The idea is almost always the starting point, and then I find the right materials for it. Then through the process of working on a piece, the nature of the material starts to inform it and give me ideas for other pieces, so it’s kind of a cycle really.

Often, the senses and sensations you explore go beyond the realm of the human, such as simulating the vision of a bee, who see the world through a distinct colour spectrum. What drives this anti-anthropocentric approach? What do you hope to make people see by inviting them to look through the eyes of a bee, for instance?

I already know what it’s like to be a human on Earth, and I’m more interested in discovering the unknown. Of course every person has a different understanding of the world based on past experiences, but more or less we all have the same biological kit for perception and cognition. I’m very curious about what other worlds lay just beyond our reach, whether that’s in outer space or even here on Earth. For example, how do other species experience the world cognitively and emotionally? I recently learned that sperm whales’ echolocation also transmits a sixth sense of extreme empathy that allows them to sense other whales’ feelings and intentions over a distance – and there’s probably more to it that’s beyond the capacity of understanding in our human brains. Given the current state of the planet, it doesn’t hurt to encourage a little empathy with other species, to remind people that there are other living beings we share this planet with who feel the consequences of our actions.

Although the materials and processes you call upon vary widely across your works, they are all unified by a meticulous technical precision, from the geometric craft behind your sculptures to your canvases that chart Pythagorean systems of sound. What is it about structured systems that appeal to you?

Probably it stems from a desire to find order amidst chaos. I’ve always been very analytical and good at spotting patterns; so structured systems naturally make sense. Theoretical physics is particularly appealing because of frameworks like string theory and quantum loop gravity, which provide answers to the big questions around time, space, and creation that have always haunted me. There are structures in my work around systems of belief, ritual, or the future that ask, “What if?”: What if humans went extinct in five thousand years? What if you could see sound? What if the deep sea and deep space were connected? I’ve found that the most effective works have a slow process of discovery, where the more you look, the more you sit with it, the more is revealed to you – so I stretch these ideas out over the physical and visual experience of the work, to the emotional and philosophical experience that emerges over time.

In contrast to the scrupulous attention to fractions and spectrums that are prevalent in your paintings, your neon works are much looser and more fluid. Do you veer more towards the systematic or the spontaneous in your work, or do you oscillate between the two, depending on the subject or medium?

Usually the ideas I have come spontaneously, triggered by something I’m reading, or have seen while in meditation. They always change to a certain extent when coming into reality though – some things just don’t work the same in the realm of imagination as they do in the physical plane. So it’s a balance between the two as there’s a general direction in which I’m driving the work, but am open to the desires of the work itself.

A single stool from Habitat has provided the very literal mould of the recurring ‘wormhole’ motif you revisit in many of your sculptures. Why do you think you keep returning to this specific structure?

It’s a symbol of change for me – not the ‘before’ and ‘after’ but the in-between, the process of getting from one state to another, the transformation, the connection. I was working with the archetypal symbol of the gate before in my paintings, and realised it was the passing through that really interested me. Both the wormhole and the gate are portals, it’s just that one is more extruded than the other. It’s a very seductive shape to me physically, and the concept itself sits in that liminal space between imagination, abstraction, and reality. It’s a model of something purely theoretical so it’s open to interpretation. I quite like the version in the film Interstellar, which is like a three-dimensional looking glass.

Could you tell us more about the Buddhist retreats you often attend and credit with igniting your productivity and creativity? What is it about these periods and these spaces that turns your creative cogs – the isolation, the introversion, or something else altogether?

A few times a year, I go to a Soto Zen monastery in south-western France. It’s a chance to realign with both the cycles of nature and myself – we wake up at 5am to immediately sit in meditation, and there are usually three periods of that each day for an hour, with ceremonies, communal work, meals, and philosophical discussions over tea in between, then we go to bed at roughly 9pm and do it all again the next day. Everything is quite structured, which frees my mind from menial thoughts about deciding what to eat next, my appearance, socialising, or productivity. Without having to worry about these mundane things, my mind naturally starts to generate new ideas. It also helps to be surrounded by the mountains, the lake, the forest, and the philosophical insights of a Zen master. Last time I went, I received ordination from a visiting priest from Eiheiji Temple in Japan. There was a full week of rituals and ceremonies for purification, gratitude, honouring the lineage of transmission. Some were quite elaborate and secretive. It was quite inspiring. The displacement of time in these ancient rituals being performed today is really striking, and the fact that it’s performative without being contrived.

When it comes to curating your shows, you often install your works in unorthodox configurations – hanging your sculptures from the ceiling, for instance. What experience do you hope to create for the viewer and what is your attitude towards a hosting space? Do you seek to work with or against it?

I want to transform the space into something out of the ordinary. My visual language centres so much around different forms of portals, and I suppose when you step into any show, you’re also crossing a threshold between the ordinary world (what you know) and into a space that offers other ways of seeing things (the unknown). I want to bring that out as much as possible to completely transport the viewer. Most shows that I’ve had have been in white cube type spaces which act as a blank slate, but I’d quite like to work with more loaded architecture, like period buildings or churches. My ultimate dream would be to do an installation in a Buddhist temple because that contemplative practice and philosophy is a significant influence on my work, and because that would complete the transmutation of my work into an actual ritual object.

You indicated you are particularly interested in creating artworks for public spaces. What do you think art does or can achieve within the public sphere? Why is it important to take art outside of four-walled spaces?

It creates a direct dialogue with the outer world, whether that’s a public square, a council estate, a park or a garden. This is important for both opening up access to a wider audience, and re-contextualising the work so the conversation doesn’t become too insular. In terms of practicality, sometimes the work just needs to be in an outdoor space, amongst the trees, near the sea, or under the open sky.

One idea for a public commission that you showed us involved placing works underwater in order to hear the sounds of living organisms. Is the premise behind this idea to create a new sonic experience for the public, or is there a more pointed message behind this invitation to listen to and engage with the natural world?

More than anything, I’m interested in revealing hidden dimensions and worlds that are so close to our own but for whatever reason, we don’t encounter on a day-to-day basis. There is so much about the ocean, for example, that we don’t know to the point that it’s comparable to deep space. So one part of this work is about expanding people’s level of consciousness, which might make them wonder what other invisible worlds are around them that they aren’t aware of.

FUTURE

The VR project you’re working on explores a ‘post-human future’ – does this serve as a warning, or simply an exploration of a reality beyond our present comprehension? Is this a reality you welcome?

It’s mostly an exercise in travelling across time and embodying other species to explore what the Earth might look like after humans are gone and speculate what our legacy will be. I love imagining a completely re-wilded planet, which I suppose goes back to your first question and my longing for nature. It’s not necessarily a reality I welcome – that is, I don’t have strong feelings about it either way – but it’s one I accept.

Tell us a little more about this project. Will it be exclusively virtual, or will it also involve physical engagement and interaction? And, crucially, when will it be launched so we can experience it for ourselves?

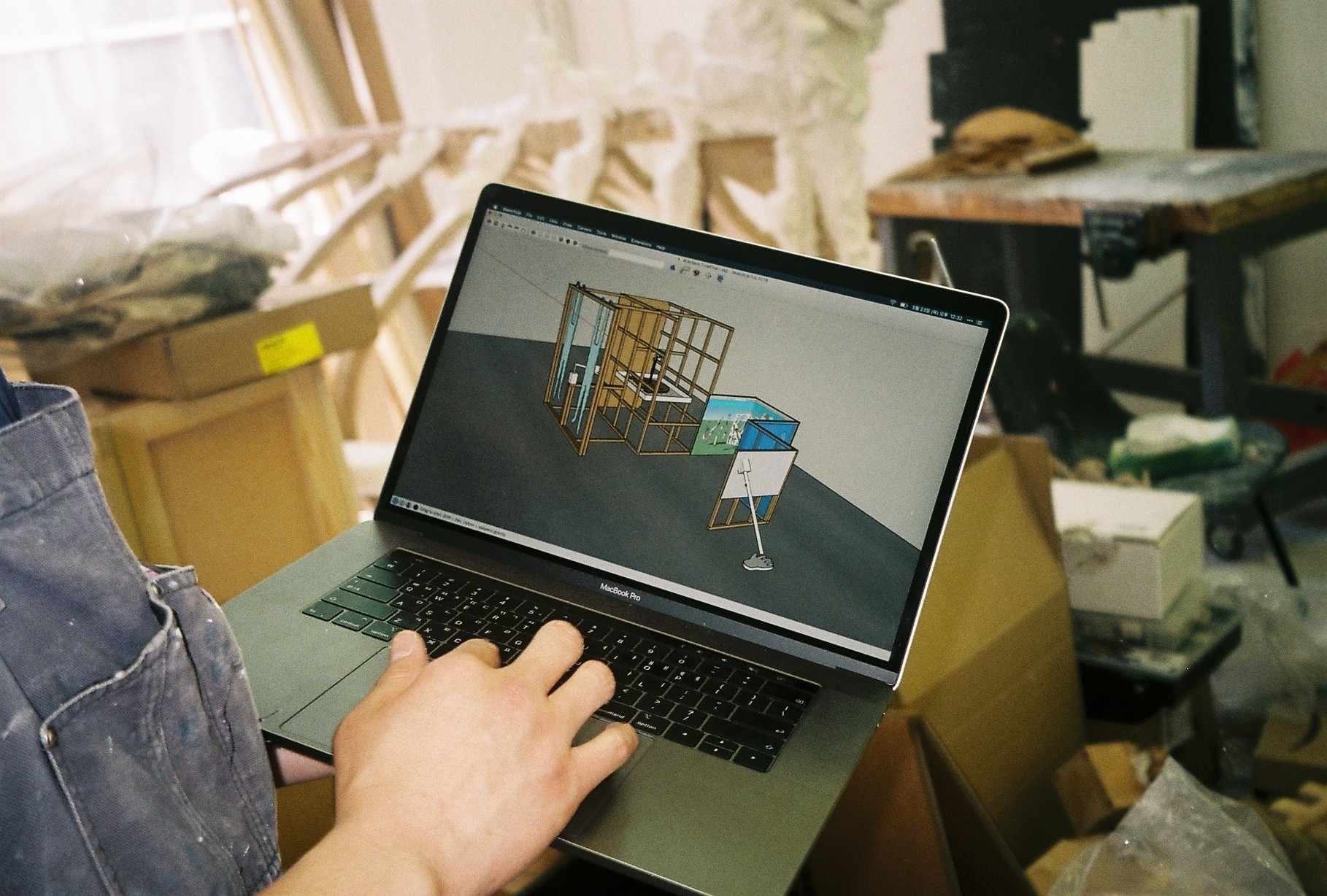

The VR game is housed inside a sculptural installation that acts as the player interface: you sit inside a flower cocoon/nest pod, wear a sound-vibrational vest that provides haptic feedback, as well as a customised VR headset that’s shaped like a speculative future species of bee. So you’re experiencing the perception and cognition of a bee in game, and physically you’ve also undergone a level of metamorphosis. I’m translating the experience of a bee into human senses not just with visual perception, but also with smell, sound, touch, and taste. I’m on track with my collaborators to launch a beta version in April 2020 and demo it. From there we may develop it some more before an official launch.

You describe your practice as trans-disciplinary. Are there any specific materials or disciplines you hope to experiment with next?

I want to construct a ritual performance with choreographed dance and music. I’d also like to return to bronze casting on a larger scale, and to work more with immersive technologies.

Do you have an ultimate goal for your practice – a particular public space where you would like your work to feature, or a piece you’ve always wanted to make – or are you concerned more with process than product?

One of my ultimate goals is to build a sort of temple/laboratory space out in the countryside where I can do really site-specific installations, exhibitions, and performances. It would be sort of like the monastery I go to in the sense that it’s a place for people to retreat and reflect surrounded by nature, but the experiences they have would be more existentially disorienting. So maybe it’s more like if someone encountered a spaceship in the middle of nowhere and by visiting, their sense of reality was completely called into question. Maybe there’s even a vague sense of having been experimented on and transformed – but in a good way.

Are you fearful of or excited about what changes our increasingly digital world will present for your practice, and creative practices at large?

In general, I feel the integration of technology is just part of the evolving role of the artist. Maybe it’s because I’m fluid when it comes to medium, but I absolutely embrace technological developments like VR, AR, AI, and machine learning as tools artists can use to reflect the changing world around them. So much of our lives are spent in the digital dimension now, so it makes sense that art is going to reflect this. Even my paintings are technologically supported since I use 3D modelling software to generate sketches, which I then paint from.

03.02.2020

Words by Kateryna Pavlyuk

Related

Studio Visit

Yambe Tam

Interview