Reinterpreting the urban environment.

Artist Florentine Ruault is as globally orientated in her thinking as she is in her making. Taking inspiration from biomimicry, neuroscience and architecture, her works are magnets for societal and environmental investigation. The artist’s reflections on the consequences of globalisation are firmly rooted in her practice, with her sculptures aiming to be “unique”, “alive” and “fractal” to push back against city homogenisation. Alongside creating pockets of variation in our cityscapes, the artist reveals that her sculptures are societal interventions to reverse the effects of our current city designs, namely increased rates of depression, addiction, loneliness and stress-related disease amongst populations. To combat this dark side to urbanism, Ruault harks back to our natural origins as a way to examine and propose alternatives to these social issues. To create these interventions, Ruault explains to me that she begins with small maquettes before scaling up to work industrially, enjoying the process of taking full ownership of her projects from start to finish. I caught up with the artist in her London Fields-based studio earlier this summer, to delve further into the thinking and processes that underpin her interdisciplinary practice.

BACKGROUND

You took your Fine Art BA at Chelsea College of Arts in London, but you originally come from Paris. Why did you decide to study here and not in France? Did you find the approach to teaching in England to be much different from what you were used to?

I wanted to genuinely discover a new culture and going to London felt like the right move. I felt closer to London’s open-mindedness and freedom of expression. Living here empowered me to embrace my true personality, which unquestionably gave me more confidence in my work. I haven’t noticed any major differences in the teaching approach between France and England. However, it is typically very British to be cautious with “health and safety” when creating or installing artworks compared to what happens according to my friends in France.

With your family working in many different sectors, from architecture to luxury event management, would you say that your relatives have influenced your interdisciplinary approach?

I have been brought up with strong values such as perseverance. I have learnt to push my boundaries and work hard until I achieve my goals. I don’t come from an “art aficionados” family so, at first, it was a challenge to choose this career path. However, my parents’ works and passions have definitely influenced the person I am today. My mother gave me an early insight on how to run a company, with the dedication and sacrifices it entails, which has influenced the way I run my studio today. Additionally, I have seen my father drawing plans during my entire childhood and if you look at my sketches, they echo architectural drawings.

WORK

When previously visiting your studio, you spoke about how you are inspired by many different disciplines in your practice, be this biomimicry, urban planning or neuroscience. How do you uncover these areas of interest? Do you collaborate with individuals working in these fields?

I have recently identified these as the core topics of my practice. I take biomimicry and neuroscience into consideration when I am developing new projects. Indeed, they influence their shapes and concepts. For instance, “The Wave – Summer City” was based on the sea’s movements and fractal appearance. Besides this, I have also started a conversation with a neuroscientist, which could lead to a collaboration. It was outstanding to hear an acclaimed neuroscientist confirming facts that were only intuitions in my practice. It has been proven that our current city designs are increasing sadness, addiction, loneliness and stress-related disease. It’s uplifting to know that there is a community that is willing to solve these social issues. Furthermore, I plan to develop my installations in many different cities, which means that I’ll be working closely with urban planners.

You’ve previously adopted a very graphic language in your practice through using Illustrator to create images of city spaces that focus on shape and line. How would you explain your transition from this way of working to sculpture? Do these methods coexist in your practice or does the computerised form clash against the more organic textures in your three- dimensional works?

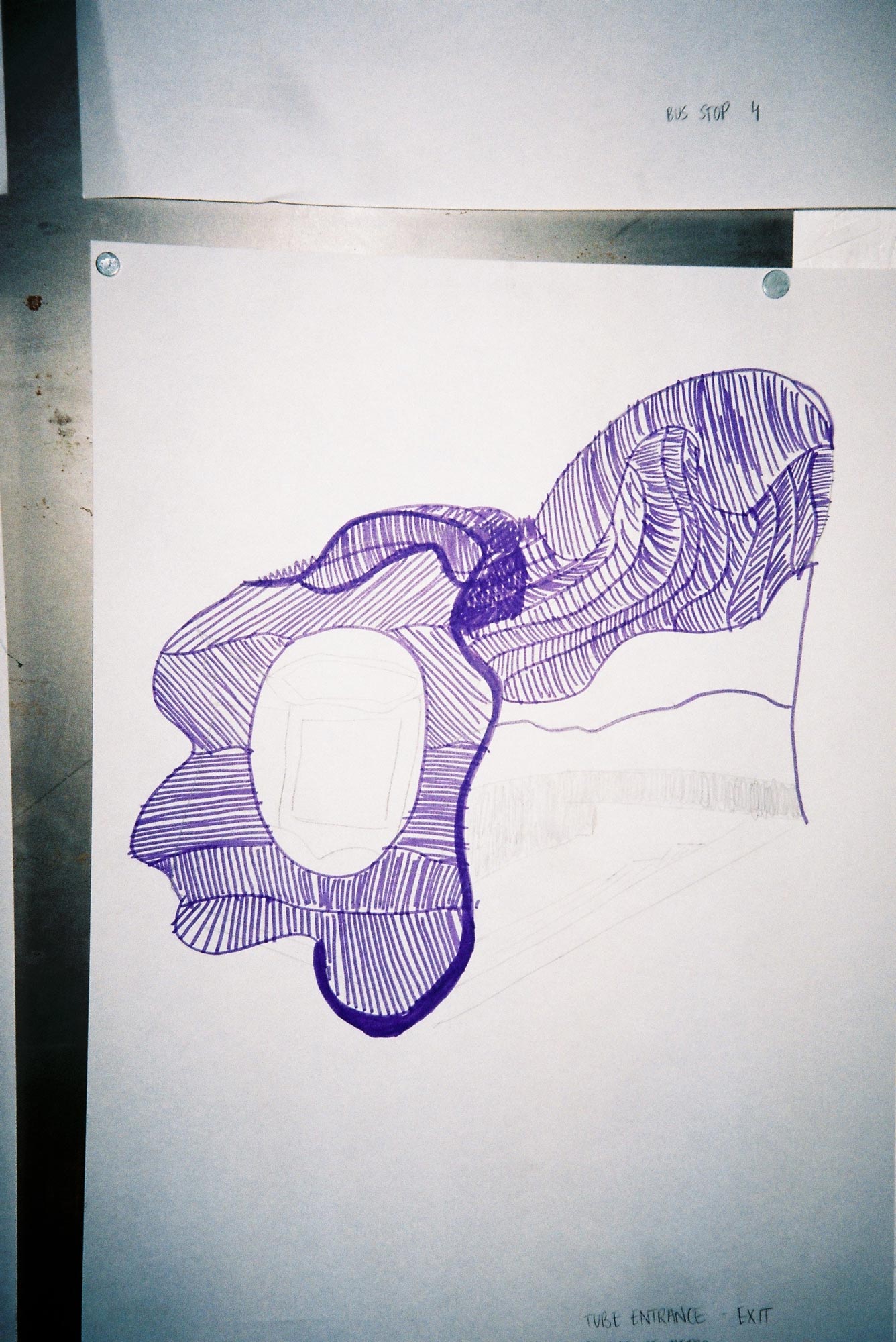

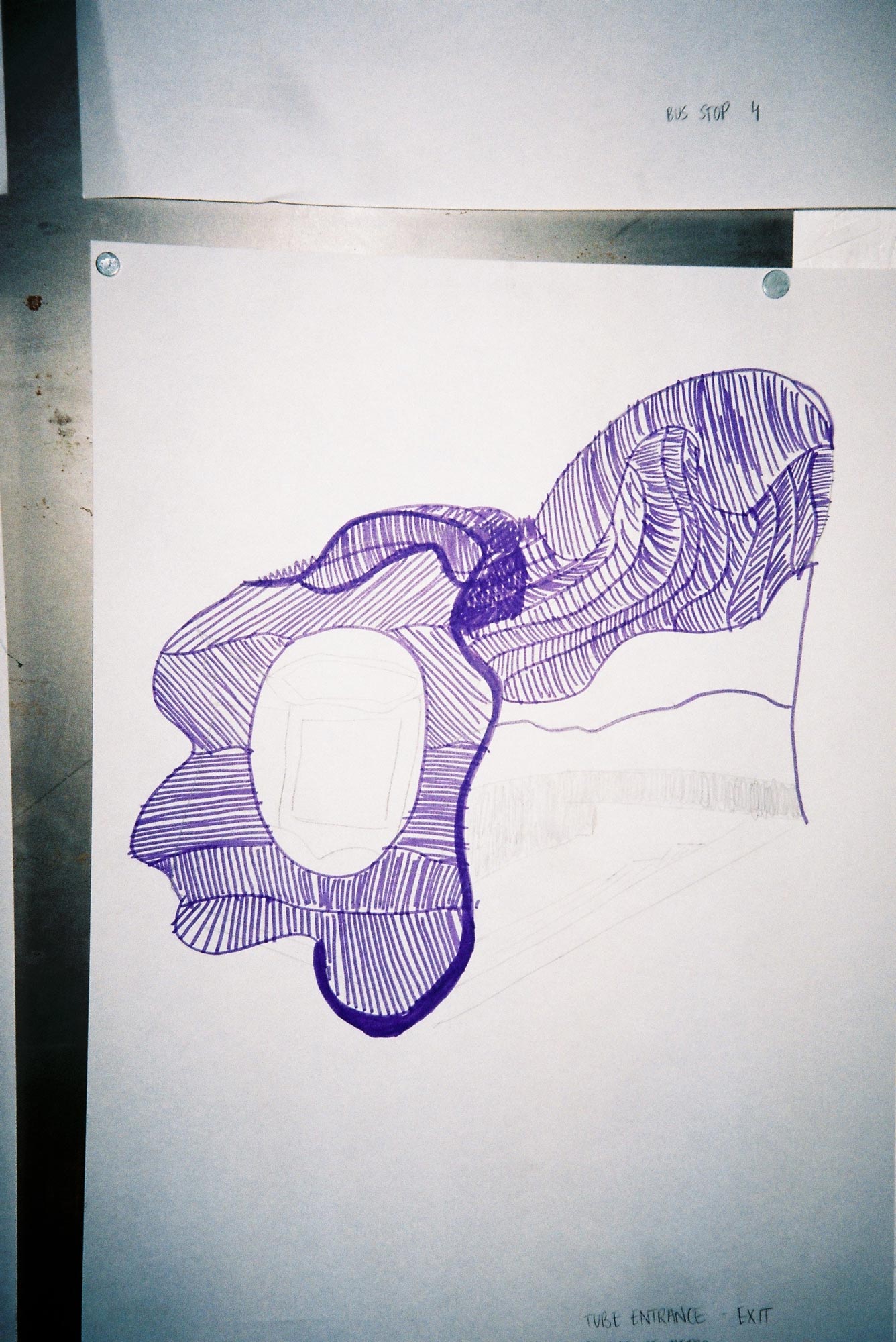

My drawings are my interpretation and understanding of city designs. The drawings are meant to expose the societal issues I’ve noticed whereas the sculptures are my propositions to fix these issues. Both are necessary and interconnected. They also share a similar visual aesthetic. The coloured series of drawings aims to challenge perceptions of the environment. The shapes are extracted from real city design and then applied with a linear pattern. Line orientations and colours are determined from the perspectives and shadows of the architectural elements. I got rid of the pattern in “Super Cities” to explore an alternative way of highlighting my perception of the issues of cities. Besides this, it is the only series of drawings that I’ve made digitally. The other ones are all handmade, from A3 to A0, and the laborious process is very similar to the sculpture’s one. It’s about drawing each line perfectly straight by hand for hours and weaving hundreds of meters of thread to add textures to the space.

Looking through your portfolio of artworks, you appear to have a fascination with lines. Where does this interest originate from?

I am obsessed by the geometrical aspects of certain urban environments, which are so different from the fractal natural habitat we used to evolve in. My practice is a reinterpretation of linear city design with a new function: it is not a shape anymore; it has been transformed into a texture. Playing with line also means that I can trigger optical illusions and, for example, trick someone into thinking that an immobile shape is moving. In my practice, using line is a way of shifting perspective whilst using similar linear urban codes.

Given the monochrome palette of your previous ‘Super Cities’ body of work, I’d also like to ask why this quality is chosen for your sculptural works and not that series?

In this series, I aimed to remove the cultural and stylistic features that are distinct to each city. The result is a graphic interpretation of multiple cities, which become inseparable in the way that they are depicted. I wanted to share the impression of “déjà-vu” that I’ve felt many times when traveling in dazzling white light through tubes and industrial elevators, or wandering along indistinguishable high streets. “Super Cities” refers to city homogenisation; a process that is currently increasing in many developed city urban landscapes. On the other hand, the sculptures aim to be unique and alive which the exact opposite of the concept of this series.

I noticed that your three-dimensional works are very bold in colour, with tones similar to Jean Dubuffet’s noteworthy reds, blues, whites and blacks. Why do you choose to involve colour in this way?

In my opinion, colours are connected to brain activities such as emotions and experience. I’ve noticed that many of our current city environments are dull. I place colourful installations in public spaces as way to inject energy into lifeless surroundings. If we take a step back in French history, the cathedrals were covered in sumptuous tones and household interiors were much more colourful. This colour phenomenon was, and is, present in many different cultures from the blue streets of Chefchaouen (Morocco), to the murals of Chichén Itzá (Mexico).

Your sculptural works are ambiguous in shape, with them almost replicating strips of DNA or soundscapes. What influences their form?

Their forms are organic inspired by a mix of biomimicry and shapes that I have been doodling since I was a child. Biomimicry can be defined by being inspired by natural forms and science. I want to incorporate nature-inspired-design in urban environments and contribute to creating fractal environments as these are scientifically proven to be better for our mental health. It’s as a game to me, almost as if I’m drawing on top of cityscapes to add more curves into our daily environment.

Are you strict with their measurements and angles before the building process?

It’s an essential part of process. From the initial idea, there are only two times that the measurements can change. I start by sketching an idea I had whilst in the streets, and then I draw the building process with details such as approximated size and materials. To adjust the perception of the piece, I often make variations of human-shape-sizes when tracing them on the floor. From this stage, I know my exact measurements and I can calculate how much aluminium I need. This means that I work with a limited quantity of materials, implying that the only reason I would change the measurements would be to fix technical issues. Creating one sculpture also inspires me to create other sculptures with different measurements- it’s a constantly evolving thing.

Your sculptures are formed using the same techniques and base-materials, creating a shared language between your works. This mirrors current processes of globalisation, where cultures across the globe are becoming increasingly interconnected as distinctions and borders begin to blur. Do you consider this to be a prominent concept in your practice? In this sense, are your works dealing with unifying spaces and individuals?

When placing my installations in the cityscape, my intention is not to unify spaces. The sculptures aim to belong in specific cities, those that are developed under capitalist systems, to challenge their city design. Hence, these “mega-cities” share a number of identical elements such as endless highways, massive buildings, subways and airports. I have conceived various projects over the past year in which I’ve been, for instance, exploring the future relationships between humans and technology whilst questioning the impact of digital on our evolution. My work aims to start a conversation within its audience and trigger interpersonal interactions between viewers.

To create your works, you go through a very labour-intensive, physical process by welding, bending and punching holes in metal. This way of working is typically recognised as a more masculine behaviour, since historically, women were shut-off from such industrial work. Do you have your own tools or do you visit workshops?

I own some basic tools such as my Makita brushless motor drill. I have also created a specific tool for my practice, which is a jig from my time in the Chelsea’s workshops. I learned nearly everything I know about metal making with the instructors there. I can do most of the “small” work in my studio, but I don’t have industrial machines yet. Therefore, I rent a working bay in workshops such as Building BloQs or London Sculpture Workshop. Being a woman isn’t hard in this industry, it’s different. I have sometimes seen dubious looks when I arrive in a new workshop or have felt little bit of pressure when using the machines for the first time. I don’t know if this pressure comes from my desire to reach my goal or the peer-pressure within the community. I like handling my projects from scratch to finish, which has led me to learn a vast set of skills. It’s still mostly a male- dominated industry but most of them are happy to see more women joining the ranks. We are all connected with our passion for the physicality of making, it’s that simple. I prefer it when people question the concept behind my pieces rather than asking gender-orientated questions. I know many female makers, I am not an exception.

To create such intricate sculptural works, are maquettes essential in your design process?

I sometimes use scale models before creating a piece, as they allow me to correct the most recent technical details. Most of my maquettes are prototypes enabling me to experience shapes and texture in space. My projects are usually life-size but creating them in a smaller scale at first allows me to give life to an idea at a lower cost than creating it full scale.

What are your other methods?

I come from a photography background, which explains why I take a lot of pictures when I am walking in the streets, capturing striking scenes. I use these pictures for documentation of current urban environments but they can also be canvases for new projects. Wherever I go, I always have a sketchbook and a pen with me. I sketch spontaneous ideas, write down inspiring parts of books that I am reading, my thinking process as well as references that I have been given. It’s multiple puzzle pieces that create one idea when assembled together.

Your piece entitled ‘The Wave – Summer City’ is heavy, yet the artwork in its arch location appears almost weightless. Is altering the audience’s perspective a deliberate consideration in your practice?

My installations are designed for the audience to experience. Playing with the audience’s perception of the space is a way to access alternative possibilities. When I am integrating an installation into the urban landscape, such as with ‘The Wave – Summer City’, I aim to create a new social space with its own aesthetic and functional codes. It’s a place to feel, relax, and interact. It’s not so much about altering someone’s perspective, but proposing an alternative to current cityscapes.

Christo and Jean-Claude are a prominent influence in your practice. Who (or what) else inspires you?

When being inspired by our contemporary and future society, as well as urban intervention combined with a twist on colours and perceptions, there are multiple artists I respect and admire. The universe of Korakrit Arunanondchai’s installation ‘A Room Full of People With Funny Names 3’ was the first time my jaw dropped for several minutes right from entering the room. He successfully takes the audience into an alternative reality, with a futuristic glitch. Carlos Cruz-Díez is a figure I’ve looked up to since the very beginning of my practice. I admire his innovative research on colours and integration into architecture. These thorough measurements create a perfect illusion that is widely accessible to the public. I also draw my inspiration from science-fiction movies and literature, as well as architects.

FUTURE

Seeing as you’ve been part of exhibitions in both London and Miami, and your artworks themselves are inherently global, do you have plans to work in any other cities?

I want to take part in changing the appearance and living conditions of future cities. My goal is to create two types of interventions. The first being an art piece, an integrated ‘add-on’ of the city’s existing architecture, with the intention being to twist the environmental perception. For this project, I want to interact with cities such as New York, Tokyo, Berlin or Paris. I’ve chosen these places as they have a similar identity, even though each has its own iconic features. I want to make giant and delicate city interventions to shift the urban environment’s impact on an audience’s health when experiencing the pieces, as if they were meant to be here. My second potential intervention is to collaborate with architects to develop the cities of tomorrow, not making the same mistakes we previously have. I want to incorporate local cultures in the design of emerging cities, rethink the materials we’re using and be aware of the upcoming challenges of our society. Some of the cities I want to collaborate with for this project are Nairobi, Rio de Janeiro, Marrakech and Phnom Penh.

02.09.19

Words by Laura Gosney

Related

Studio Visit

Florentine Ruault

Interview