The Fantasy of Nature

I.

The king doth keep his revels here to-night:

Take heed the queen come not within his sight;

summerlight summerdreams summerbabes

For Oberon is passing fell and wrath,

Because that she as her attendant hath

hotboysummer queerindian gayartist

A lovely boy, stolen from an Indian king;

She never had so sweet a changeling;

impish boysinnature nymphs

And jealous Oberon would have the child

Knight of his train, to trace the forests wild;

natureboy suffocatinglove entwined

But she perforce withholds the loved boy,

Crowns him with flowers and makes him all her joy:

hogsweed briarrose carnivorousplants

And now they never meet in grove or green,

By fountain clear, or spangled starlight sheen,

queermysticism eveningglow drowning_art

But, they do square, that all their elves for fear

Creep into acorn-cups and hide them there.

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

hashtags from recent Instagram posts by @jakegrewal

II.

Lovers disappear among the trees, their identities and affections blurred by the onset of a magical night. Is there a moon or isn’t there? Is it May or June? Time is bent out of shape, the lovers’ minds transfigured. Wildflowers and their properties are named and used in magic spells. Spirits sing and dance, tripping among the cowslips and acorn-cups. A group of workmen practice amateur dramatics in a clearing. Titania and Oberon fight over an Indian changeling child. Among the strangeness, sexuality becomes ambiguous; the narrative is shaped by queer disruptions.

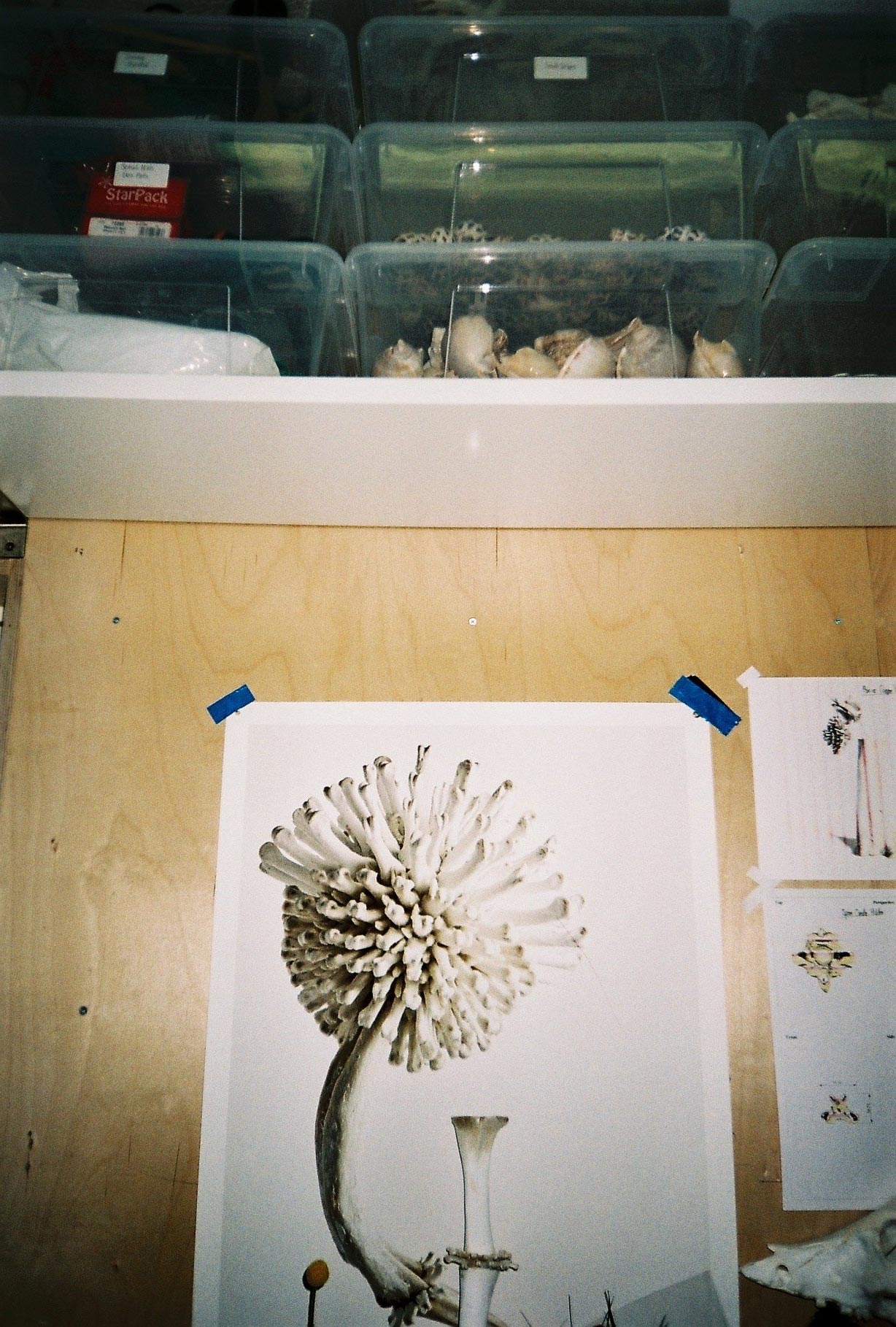

William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a key point of reference for Indian-Welsh artist Jake Grewal. His coloured-pencil drawings and oil paintings depict boys in nature – usually naked, often entwined with plants or the limbs of other exploring boys. There is a sense of fantasy, of being out-of-time and out-of-place, of queer disruption.

Grewal evokes ambiguity throughout his work, whether in his medium – coloured pencil marks that resemble brush strokes – or in his visual references. There is something ethnographic about many of his drawings, and yet the colour palette and the plants/landscapes depicted are primarily drawn from memories of Grewal’s Welsh heritage, avoiding a tropical or overly exotic aesthetic.

His characters are ambiguous too: simultaneously childish and homoerotic, their expressions frequently trace a fine line between pleasure and pain. In one drawing, two boys lean back among a bed of white flowers, mouths open. Is it agony or ecstasy? And is the feeling caused by each other, or by their contact with white-petalled hogsweed, which can cause severe skin irritation and even burns? However, many viewers won’t recognise hogsweed or know its effects; Grewal evokes a language of flowers which is esoteric, taking its vocabulary not from well-mannered garden flowers but from the unrestrained weeds and so-called “invasive” plants that lurk on the boundaries.

Meanings flow into one another, just like everything else in this fluid natural-cultural world. There is a tension, never quite resolved, between what elements of the natural world mean to themselves, what they mean in a cultural sense, and what they mean to Grewal. There is a personal and artistic mythology at play in these images, but it is more evocative or poetic than systematic.

Grewal’s drawings and paintings suggest both the fantasy and reality of “nature”. Our vision of nature as an untouched, “other” realm is imaginary, reinforced by our perceived disconnection from it in the technological age and by our post-colonial habits of exoticizing and fetishizing the non-mechanical. Yet at the same time, the natural world palpably exists as a place of bodily and mental pleasure and pain, interwoven with the very fabric of our lives. The boys of Grewal’s images have a connection with the natural world which is mysterious – somehow both instinctive and uneasy – embodying the in-between-ness of our relationship with our environment.

These images also suggest re-enchantment with nature. It’s something that might just have the power to save us from ecological collapse – a re-recognition of the myriad ways in which humans are interconnected with the nonhuman world, and an acceptance that many of these modes of connection are mysterious. These naked boys in nature and embracing uncertainty and the unknown – and so should we.

At the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Queen Hippolyta suggests the young lovers’ minds have been “transfigured so together”. The events of the play, she hints, have been a shared dream or vision; but they have had real consequences, and the various love triangles have been resolved. In the final lines, the eponymous Puck further suggests to the audience that they themselves have been dreaming:

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear.

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

But asleep or awake, re-enchantment has the power to save us, especially when that re-enchantment is shared with others. This is because our dreams and visions shape us psychologically, affecting our actions and our perceptions of others. Perhaps, Grewal’s naked boys suggest, we can dream ourselves back to reality – that is to say, back to nature.

III.

Tanned limb against yellow bark, boy and tree, both naked. Soon his grandmother will call him in for dinner. In the meantime, he dreams of thin wrists and the erotic nape of a neck. Nostalgic for summer even in its midst, he watches reflections on the stream-surface and thinks about drowning in its coolness. Wildflowers send their seeds floating past his climbing tree, or exude their romantic stink in the half-light; vines, cuckoopint, briar rose and hogsweed. The forest floor is alive with creepers and carnivorous plants, mysterious and not-quite-comfortable in their surroundings. The impish nature-boy jumps down from his perch, lured by his grandmother’s cooking and the memory of illicit love-letters under his bed.

11.11.19

Words by Anna Souter

Related

Journal