The Manchester-based collective share their incentive to loosen up a little.

Earlier this year, Manchester-based collective Rhino made their curatorial debut at Castlefield Gallery with ”Th-th-th-that’s all folks!”—a show aiming to provide a breather from the serious and stale offerings of contemporary exhibition practice. Rhino’s eclectic display of work wasn’t quite a breath of fresh air but a deep inhale of laughing gas and exhale through a mouthful of Juicy Fruit bubble gum, uniting eight artists that celebrate childhood nostalgia, imperfection and making art for the fun of it.

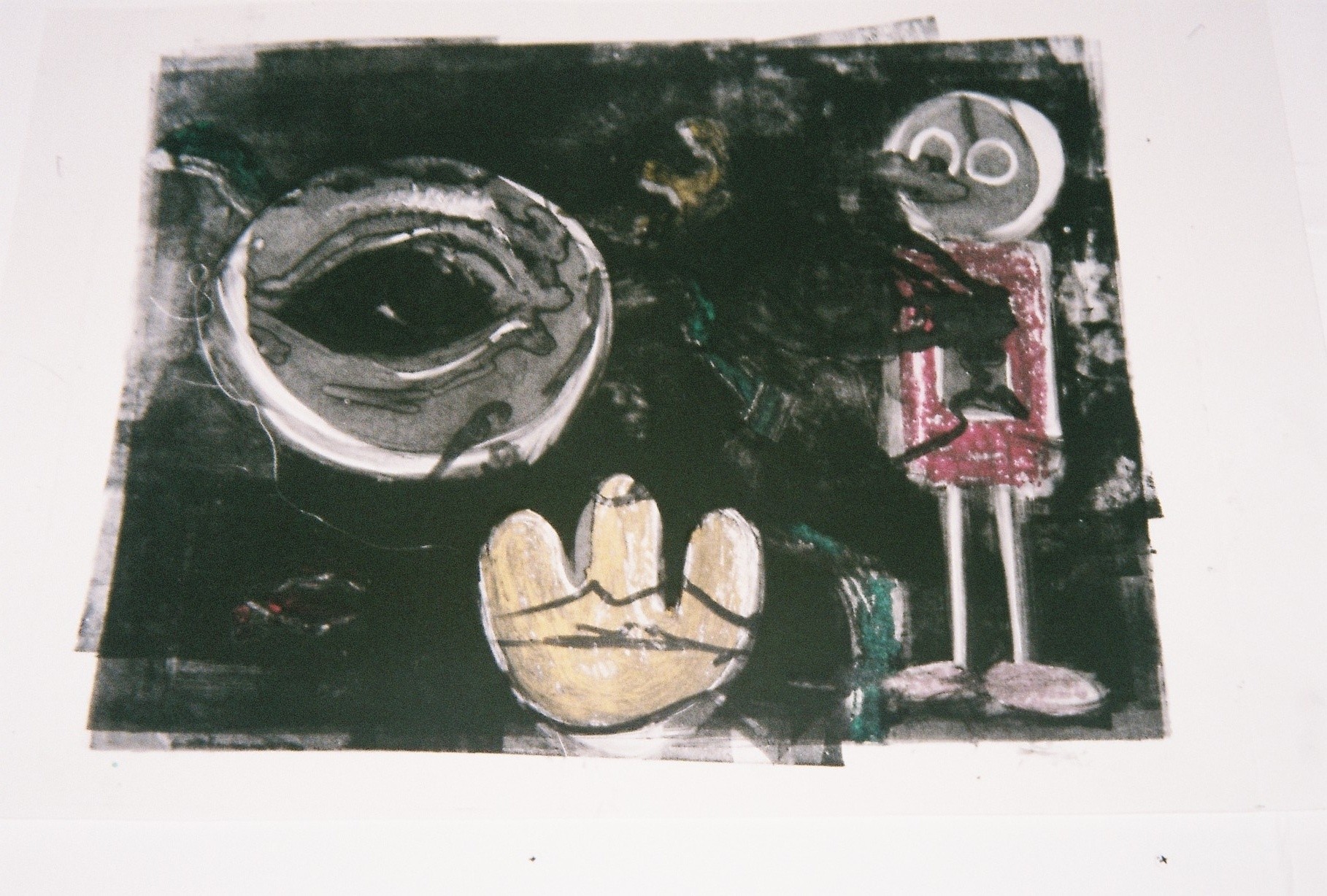

Visible from the upper and lower levels of the gallery, Rhino’s feature wall—sky blue, dotted with white clouds—teamed up with scattered edges of Astro Turf to loosely frame the work in a playground-like setting. Cig ends littered the fake grass. “Th-th-th-that’s all folks!” brought together the abstract, kinetic sculptures of Millie Layton, Jamie Fitzpatrick’s grotesque and drooping wax-work military figure, and three bold paintings by Alfie Kungu, his imagery hailing from somewhere between the imaginary and everyday life.

On entrance to the gallery, Kungu’s ”3 Hammered Nails , 2017″ introduced the show’s focus on materiality, wit and double meaning. These themes particularly manifest in James Lomax’s “Down the Path , 2018″ that installed a slab of chewed-up, spat-out Hubba Bubba pieces under an utterly useless concrete magnifying glass. Smeared across the gallery’s downstairs wall were the muddy fingerprints of Fitzpatrick—a splash of brown wax that appeared to have been kicked up by the legs playing football in Kungu’s neighbouring work, ”On the Ball , 2017″

The stylistic incoherence of ”Th-th-th-that’s all folks!” was forgivable as the assortment of a pick ’n’ mix bag: Rhino brought together sweet and sour works as if writing an episode schedule for Neil Buchanan’s colourful (yet somewhat uncanny) Art Attack. As recent graduates of Fine Art at Manchester School of Art, the four members of the collective created a environment at odds with the seriousness of immaculate white walls and the box-ticking of art school assignments.

Allowing the dust to settle after the de-install, I spoke to Rhino’s Emily Chapman, Liam Fallon, Tulani Hlalo and Meghan Smith to find out about the inspiration for their first exhibition and the incentives that define the collective.

I heard that whilst studying together at Manchester School of Art, you were responsible for organising your fine art final year degree show. Tell me about the common interests or processes that initially brought you together.

Tulani Hlalo: I wouldn’t say we were responsible for everything, but the four of us did quite a bit degree show-wise. What originally brought us together was the fact that all four of us were in uni every day. As bad as it sounds, there was only a select few of us that were in from open until close. Meg wasn’t in our studio but we’d all regularly visit, mostly to ask if anyone wanted to go for a stress-induced cig. Something we noticed after we had formed [as Rhino] was the links between all of our practices. None of us are serious people and I think that reflects in each of our individual practices and how we interact with each other.

Liam Fallon: Throughout the final year (and probably even before), we started to take the reigns a little and realised that the four of us work really well together. Each of us has a strength within the group, which I suppose helps to really form it. I’m a bit of a control freak and like to plan everything down to the last inch, which helps in the organising of things and then the others also have their strengths. One reason in particular as to why we came together is that all of our practices, even though they deal with varying political elements, have a certain level of humour to them. There are very few shows that we have seen that were just really enjoyable so I suppose that this became an incentive for us.

Meghan Smith: Us four were just really interested in making the degree show not suck and just sort of took over a bit. Everyone else probably hated us for it, but oh well. Through this process, I became closer to the others as I’d go down to their studios when I didn’t know what to do with myself and we would usually stay pretty late at uni. We just clicked really. It became clear that we liked a lot of the same work and we have very similar views on the world. Eventually, we all realised that if we were all sticking around in Manchester then we might as well just do stuff together and be the thing we thought was missing here. Not that we think we are god’s gift to the art world, we just want to have fun doing things we enjoy.

Emily Chapman: We were all so heavily involved in our final year so I think spending 8 to 12 hours a day together every day either makes or breaks you as friends, and so far we haven’t broken. We have spent a ridiculous amount of hours together over the past 3 to 4 years, so we naturally moulded together—a lot of beer, lists, planning, meetings, receipts, trips to Wilkos, sanding and a lot of breadsticks and hummus. Basically, we all love being in control, making work, looking at work and going to the pub.

How did this evolve into you working together as Rhino?

TH: We’ve talked about this before and we can’t quite pinpoint the exact moment Rhino was formed. I think it was quite an organic process though. It probably happened on the step we all used to smoke on outside the art school complaining about the art scene in Manchester or in Sand Bar (big shout out to Sand Bar by the way), the pub we’d usually all crawl into when third year was melting our brains. One thing I do remember is seeing Rhinos everywhere, like in logos. We had this running joke about using the name Rhino because as a Northern artist you have to be thick skinned. I guess there’s some truth in that.

MS: I think it probably got real when we wrote the proposal for the Launch Pad project at Castlefield Gallery, and then when we found out we got it, it just sort of dawned on us that it was really happening and that this was definitely a thing now.

You are all artists with your own individual practices but you decided not to include any of your own work in the show. What influenced this decision?

TH: There’s enough nepotism going on in Manchester at the moment, why add to it…

LF: I think it was also just down to preference. As soon as you put your own work into the show, your attention in some way shifts away from the exhibition or project as a whole and instead becomes focused or drawn more so towards your own work. As a means to avoid being subjective and to guarantee that all of the work is considered equally it’s important to have that compartmentalisation.

EC: Individually, we all appreciate that an artwork will always live in your own mind entirely different to any other way that it will ever exist. I don’t enjoy curating my own work in a group show since there’s too much emotional attachment involved and is a huge pressure to add to everyone. I don’t even remember the first time we stated that we wouldn’t show any of our own work, it was always just a given. Rhino was never born out of wanting to push our own names forward as artists, more to curate the kind of exhibitions that we all enjoy yet have trouble finding—I’m sure we’ll curate shows involving our own work in the future when it’s more apt.

In ”Th-th-th-that’s all folks!”, it struck me that you had made a conscious effort to transform the space into a distinctive environment of its own. Why did you decide to present the work through this frame?

LF: I think we were really adamant about creating a show that in many ways rejected a lot of the political and social factors that currently contribute to the times that we find ourselves in. Of course, anything is political but in terms of things being explicitly political, we wanted to completely avoid that. A lot of the works within the show for us drew upon these ideas of nostalgia, sentimentality and also just being a kid and I think it was important for us to encapsulate that and I suppose in some ways to wrap it up in cotton wool so nothing else could interfere or interact with that.

MS: We just really wanted to make the whole thing an experience. We didn’t just want to shove all of the artwork into another white-walled gallery. A lot of it extended from us wanting to make the kind of shows we want to see—we’ve seen enough white cubes in our time. The cloud wall and grass also framed the gallery from the outside, it caught the attention of people walking by on their way to work, or taking their kids to school. We wanted it to be inclusive and for people to feel welcome.

EC: Also, we wanted this to be an accessible exhibition. I’m tired of going to exhibitions so heavily laced in socio-political content that I feel drained halfway round, but I’m also dyslexic and struggle to retain or process information, so I always appreciate exhibitions with a splash of instant visual gratification—it eases me into focusing my energy on attempting to understand what’s going on and why. Basically, I like bright colours and flashy lights and I think deep down we all like bright colours and flashy lights.

Could you tell me about your install process for the show—any funny stories? How did you go about creating that iconic sky wall feature?

TH: Well, first things first, those clouded walls took ages but we managed to tape, cut and paint both walls in just under five days. Fuck knows how we did it, but we did! It was very rare that all of us were free to install at the same time, due to us all being poor and having to work around our full-time jobs. I’m incredibly proud of what we managed to do in such a short install time. The weather was pretty gross during install and there is this railway arch right across from the gallery that we’d smoke under and one day this rather large and very dry human shit just kind of rolled into view—as horrific as that sounds, it was pretty funny at the time.

MS: Yeah, the clouds killed me! We did sort of work out a system in the end, like I drew out all the clouds and Emily and Lani would then mask and cut them out, and then once they were all drawn, I started doing some taping and they started painting. Our main aim was to get the entrance and the double height wall done, and we were debating whether to do the other wall inside and eventually, we just said fuck it and started it and somehow managed to get it all done! I was getting pretty stressed out during the whole thing but it all worked out in the end. Also, it must be mentioned that Emily and Rufus (assistant at Castlefield) did an amazing job of fitting the grass whilst all of the wall painting was still going on! It was really enjoyable during install and we are all pretty weird people so just find really random stuff funny, like we were always waiting for Lani to arrive and one morning, there was this pigeon that looked like her that was hanging out with me and Emily and that was pretty funny, to us anyway. We also had an awkward funny moment when I told everyone that the artwork would be arriving that day and so we waited around until 8pm with James Ackerley (the best gallery tech in the world) for it to arrive and then turns out I’d got the day wrong and it wasn’t until the following day, felt pretty bad because I think we made him miss a bev with some mates, but it was pretty funny because we were really stressing out.

EC: That pigeon was just so Lani-esque it was hard to not see it in a ‘Professor McGonagall’ light. I think just the general dynamic of mine and Lani’s horizontally-relaxed approach (to basically everything) and Meg and Liam’s direct opposite approach was comical to be around. But honestly, we’re all super weird so I don’t think any of our anecdotes would appear remotely funny to anyone but the four of us.

TH: Basically, Rhino-specific deep memes.

Central to the show are themes of play, nostalgia and impulse, which could be described as qualities rare to an institution of art. Why did you want to follow such an approach?

LF: I agree that they are rare qualities and are kind of ironic in relation to contemporary art and institutions but at the same time, I think that’s one of the main reasons to why we began—to show things that bigger institutions weren’t thinking about or wanting to make shows about.

TH: As a collective, we were just bored of all these dead serious shows where you’d have to read a twelve-page essay, just to understand the core concept. The phrase ‘an incentive to loosen up a little’ was thrown around quite often during the planning and I hope the show did help people to do so. Art doesn’t have to be super serious all the time.

MS: Exactly what they said! With institutions, it can feel like they are filling a quota, and that can get real stale pretty quickly.

Your Instagram quotes: “They never did catch that Rhino.”—a line from both James and the Giant Peach and Tyler, the Creator in the Earl Sweatshirt track Sasquatch. What does it mean to you?

TH: James and the Giant Peach was one my favourite films as a child and that ‘rhino’ line has stuck with me for years. In all honesty, I put it in our Instagram bio because at the time (prior to “Th-th-th-that’s all folks!” launch) we wanted to keep things cryptic and mysterious! I’m really curious about how other people are reading into it now tbh.

LF: I think it’s a little bit optimistic, no one knows what we are going to do next…

TH: Like what Liam said, the actual context of the rhino in James and the Giant Peach is this big, unknown entity. I guess I was just a combination of that and thinking about clouds that brought it into my head at the time.

I think it also captures the dual meaning and sense of deception present in a number of the show’s works. Especially James Lomax’s concrete magnifying glass and Jamie Fitzpatrick’s sculpture, which could either be made of wax or icing for a cake. What were you trying to communicate by making your viewer ‘look twice’ at the work?

MS: We really liked the tactile qualities of a lot of the work, and it was very much about people being able to make up their own minds about what the work was or meant. It was completely subjective to each person, very much like how something from your childhood can change its meaning and importance as you grow older. It was great when we had Gabriel do his review of the show. When we read it, we almost shed a tear because it was such an untainted view of the work. He spoke about Cheetos and aliens (Millie Layton’s sculptures) and that really embodied what we were trying to achieve. Almost like a Chinese whisper. Once I’d read about the Cheetos, that was all I could then see, so maybe not ‘looking twice’ but almost a reinterpretation, and that trigger into regressing to childhood.

LF: Also, as three of us are sculptors, there tends to be a real emphasis on making and the celebration of such. It’s really important for all of us that ‘the maker’s hand’ is visible in all of the work as it takes away the ‘clinical’ that can be perceived in a lot of galleries.

Reflecting on the reception of your curatorial debut, what have you taken from the experience?

LF: Just how much effort and planning go into these shows—it’s definitely something not to underestimate…

MS: Mainly that we’ve got to accept that our style isn’t going to be to everyone’s taste, but we loved it. As long as we are aware of that, then we can maintain our integrity.

EC: And not to forget, even established galleries can be sub-zero and you will require at least three layers of clothing at all times (in maybe all art spaces—what’s the deal?!). Aside from having a good quality fleece, always execute exhibitions with integrity and don’t underestimate the task at hand. Have faith and put in everything you have.

What are you are particularly proud of and is there anything that you might have done differently?

TH: I know this doesn’t have much to do with us but it would have been amazing if Arts Council had accepted our bid. And as I said before, just how much we achieved in such a short space of time.

MS: Some funding would have been great, as we didn’t make any money from the exhibition. If anything, we lost money. We really wanted to be able to pay all of the artists but unfortunately, Arts Council didn’t get our vision. But I am just really proud that we actually pulled it off, and so many people came, which was really humbling.

LF: Same as the other said, but also for me, a little more time and maybe even the inclusion of other artists! We had some great ones waiting in the wings but maybe they’ll appear in the next show…

15.06.18

Words by Brit Seaton

Related

Journal

Making, A Life

Interview