Sweat Patch: Making Art at the Cliff Edge.

I’ve begun questioning my role as an artist in the face of climate change. I am fortunate to be living and working in Goa, India, assisting performance artist Nikhil Chopra, whilst working on my own practice in a small flat, with a balcony overlooking a tidal river. Here, electric blue kingfishers and noisy crows populate the mangrove shrubs opposite and rich, red earth feeds the crops that local farmers grow. At dawn and dusk fishermen haul by hand heavy nets onto the seashore. Unlike in London, where the infrastructure is so fully consolidated and our impact upon nature feels more distant, here in Goa the relationship between humans and the environment can constantly be seen and felt.

Fuelled by international tourism and a growing middle-class, construction work has been rapidly building over Goa’s lush natural landscape, with scattered rural villages becoming seeds of urban developments. Walking along a beach not yet cleared for tourists means stepping on shredded plastic bags or sand-filled nappies. Without a government-run rubbish collection, the free-roaming street cows are sadly doing that job, their stomachs swelling from it. Yet India is going through the changes that have already shaped Western developed countries. The UK, the first country to industrialise, has for centuries fuelled climate change. Having taken a long-haul flight to Goa and contributing on a daily basis to waste and energy consumption, I have never been so viscerally confronted with my own complicity in the global problem.

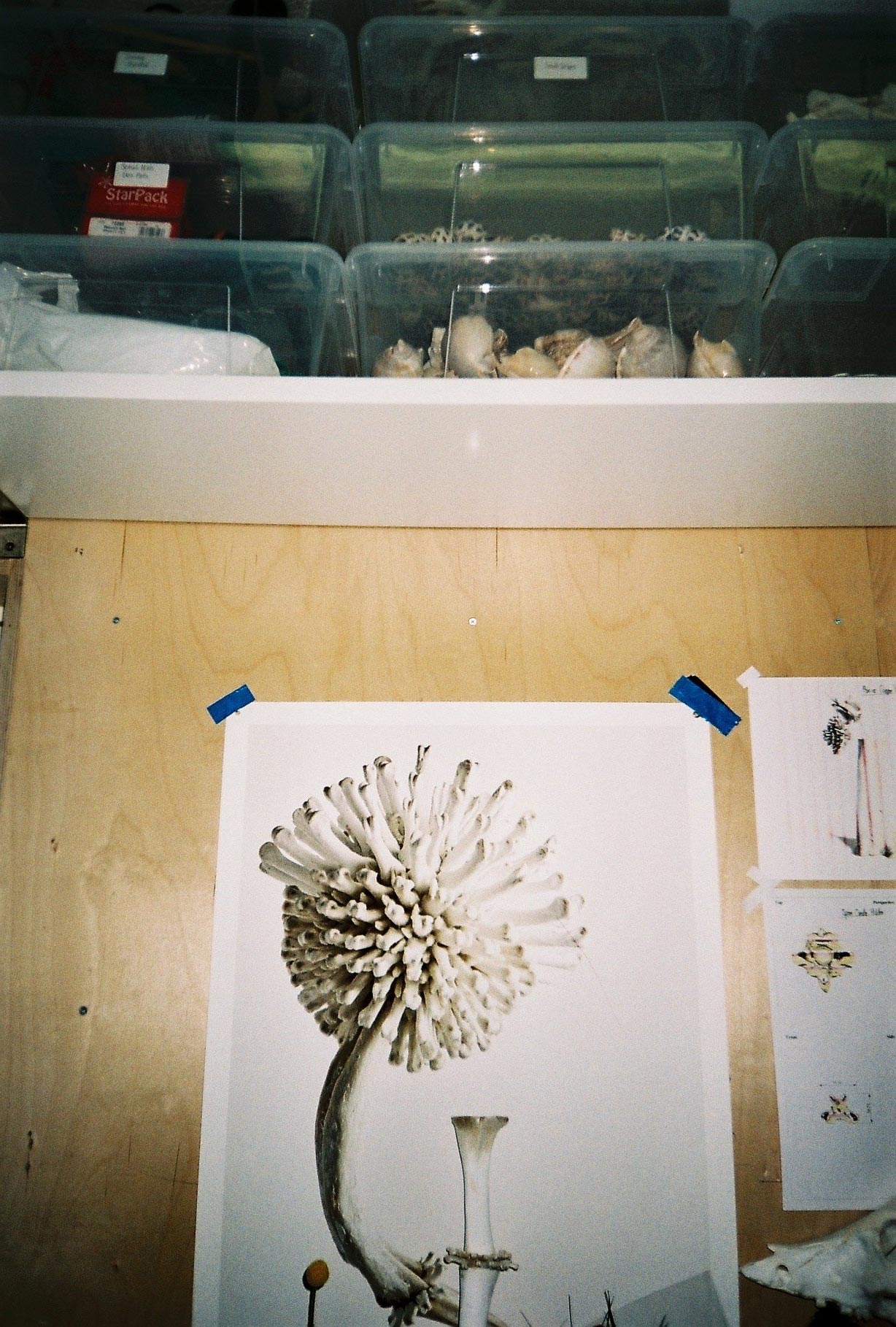

I began discussing the making of art while caught between this paradox with Shivani Gupta, a photographer and performer, who has been living here for years, witnessing Goa’s transformation. For Shivani, nature and the environment in which she lives is becoming an ever-growing subject of her work. I visited Shivani’s home and we went for a walk through some abandoned fields, dried up due to a recent incident of construction workers polluting the village water. Past the field and amongst coconut palm groves, several villas lie in ruin, as they do all over Goa, bulging trees taking root in their crumbling layers of red rock brick. Nature reclaiming its territory.

These ruins have become the backdrop to Gupta’s new video works: black and white vignettes depicting fragments of her body performing subtle gestures. Slowly these images reveal themselves to be moving. With an echo of both Surrealist painting and collage, and 1980’s feminist photography, it is the presence of nature that makes these works feel most current. In one clip, an awkward set of limbs protruding from an old window frame shuffle around aimlessly against the backdrop of a silently passing river. These absurd actions see the figure almost disappear into the wider deserted scenery, her limbs moving repeatedly on a loop like swaying branches. Her videos invite us to reconsider the spaces around us, their histories and futures, and our interactions with the built and unbuilt environment.

While nature has always been living around us, beneath us, sustaining us – and artists have throughout history drawn from, or made things out of it – the presence of nature in art today is highly charged in a new way. We continue to marvel at its beauty with awe, but also point out its weaknesses, defenceless as it is against our actions, inviting viewers to become entangled in its branches and more considerate of its urgent plea. India has this year suffered severe drought, flooding and storms of record-breaking magnitude; all of which deepen poverty, water scarcity and cause loss of livestock, livelihoods and lives.

Each of us humans with our highly developed conscience may grapple daily with our own mortality; struggling yet finding ways to keep living, making sense of, or adding to the world. However today, with predictions of imminent environmental changes leading to social and ecological collapse, we have to deal with the existentialist phenomena of the possible extinction of human- and animalkind. To then make art seems almost ridiculous. Yet it is more urgent than ever: whether the artwork is directly addressing political and humanitarian issues; or, as with Gupta’s new work, offers quiet moments of reflection on an absurd world; or through collaborative, community-driven projects. The need to reflect and create, invent and propose alternative possibilities is urgent.

This summer train tracks began to contort under 38°C temperatures in the UK’s hottest July. A comedic image of a train wobbling from side to side, enduring the route of a child’s poorly assembled toy track springs to mind. Commuters perspired beneath crisp white shirts as they heaved laptops and leftovers for lunch in rucksacks. At closed platforms, they were turned away from their daily routes and urged to find alternative ways to work. Climate change is ever-present yet elusive, punctuated by moments of intermittent absurdity that shake us from our in-built realities, even if for a brief moment.

Not only rising global temperatures, but the spread of misinformation and political caricatures playing out the theatrics on an unreachable world stage, puts many across the planet at the edge of a catastrophic social and ecological precipice. The current “climate” reflects the Absurdist thought of the 1920’s Dadaists, whose humour and irony brought to light the horrors of war that were engulfing the planet, addressing them with ridicule and nonsense. Arising again in the aftermath of World War II, the Absurdist Theatre of the 1940’s took inspiration from Dadaism and the Absurdist philosophy of Albert Camus, putting implausibility at the heart of theatre. Playwrights such as Beckett and Pinter responded to recession and degeneration of reason on the global stage by portraying human existence as chaotic and plot-less.

It seems that today the Absurdist mode of critique is relevant once again, with all of us living within a new alternative, fictional framework that creatives can occupy and work with. Andy Holden’s film essay What a Time to be Alive illustrates well this bizarre nonsensical reality, borne of the dissolving of facts. Set in 2016, his film presents a cartoon-version of himself wandering through surreal natural and man-made photographic landscapes, observing Trump shaking hands with Kanye West, whilst mumbling to himself the “truth no longer bears any weight.” Here, illogical reality is superseded by the logical cartoon.

It’s now late August and the studio is stifling. Three flights of stairs and my bag imprints a sweat-stained shape on my back. I decided to steal a few hours here between shifts at work but the creative outcome has been fruitless. Studio rituals and the meanderings and failures of art-making in the face of such environmental and social threats can feel somewhat pointless. I think of the many questions to ask and be answered. As artists, how do we navigate this era of turbulence and uncertainty? Do we weaponise with our practices, or build meaningful resistance in our numbers through collectivising? Do we retreat into our work, or detach from it? Do we reinterpret this era with nonsensical work, or scramble together a voice that reflects the mood of the planet? Do we check our mediums and processes, or find vastly different ways of working?

Camus proclaims we must imagine King Sisyphus as “happy” after pushing the boulder up the hill, despite it rolling back down again at the end of the day. For just a brief moment, he stands at the top, the day’s work complete. Like Sisyphus, despite the potential meaninglessness of creative ‘failures’, or feelings of hopelessness over the future of our sacred planet or our democracy, the only resistance we still have as artists is to keep interpreting, questioning and pushing the rock up the incline. We must keep working, in whatever capacity or direction our practices take for as long as we have the luxury of responding to the world through art. Surely to give in is to retreat into spectatorship.

Between us, we are still searching for answers. We look to Lauren Bon and The Metabolic Studio’s text piece, ‘Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale That Society Has the Capacity to Destroy’, 2017. That capacity is devastatingly – or conversely promisingly – huge.

Neena Percy and Lizzy Drury are artist-curators who formed Hot Desque, a curatorial partnership presenting emerging and established artists within immersive, site-specific exhibitions. All artworks are presented together to transform a space into a theatrical mise-en-scéne. Highlighting the interdependence of artists, we encourage cross-disciplinary collaborations to positively widen art networks. Utilising temporary spaces, Hot Desque reflects the contemporary world of ‘work’ and the expected flexibility with which many artists, practitioners and creatives must work today.

Shivani Gupta will be exhibiting her video installation Girl in a House as part of ‘Goa Photo’ later this year. She is currently working and practicing from her studio in Goa, India.

Andy Holden presented Episode IV: What a Time to be Alive, HD video, 2017 in ‘Tailbone’ at the Artesian Well curated by Hot Desque.

05.09.19

Words by Lizzy Drury and Neena Percy

Related

Journal