Finding the balance between the tragic and the comic.

Artist Shinuk Suh’s works encapsulate sin, colourism and anxiety whilst referencing an assortment of figures, from Japanese writer Haruki Murakami to cartoon character Donald Duck. This wide spectrum of ideas reflects the twists and turns the artist has taken to reach his current practice, from studying Hotel Management to serving in the army. The artist reveals that these life experiences have continually shaped him to reach his sculptural process, from using pen and paper to express what could not be spoken during military procedure, to finding painting too fragmented as a medium. Utilising silicon to mimic the touch sensation of human skin and toning socially-gendered colours into pastels, Suh analyses modern political and cultural ideas. He draws upon the unconscious through implementing wave motifs in his works, bringing us into a space where the boundaries are blurred between dreams and reality, the tragic and the comic. Interested in delving into the ideology behind hand imagery and collapsed wreckage in his work, I visited the artist in his studio at the Slade prior to his degree show, where he tells me more about the ways that psychology informs his work, how he uses movement to convey a narrative and how this story usually begins through a primitive self-examination.

BACKGROUND

It has been a long journey of 10 years involved in educational systems for you to get to where you are. Can you share with us your ups and downs in education, from studying hotel management to your current MFA at the Slade?

It seems that it took me a long time to master Fine Art. I went to university in Seoul but I did not know my aptitude. In fact, my major in Hotel Management was not my will and I just chose it because it was a major that was popular in Korea at that time. However, I was not happy at all when I was studying there, because it did not fit my aptitudes at all. After a lot of trouble, I became interested in illustration, and this was actually the moment when I started to consider art. I decided to study in London when it was recommended to me by my professor who I had grown close to, so I studied Fine Art for the first time and majored in painting at Central Saint Martins. I enjoyed painting at that time, but my work was always fragmented. During third grade, I realised that I was more interested in sculpture than painting, and so I applied for Sculpture course at the Slade School. As I studied and practiced the subject over two years, I realised that I had now found what I most enjoyed.

Whilst in the mandatory army in Korea, you started drawing human figures for the first time. Was this a therapeutic method for you to get rid of anxieties? Does it still have that role for you?

When I joined the army for the first time, the items I could take from society were really limited. Among them, a small sketchbook and pen were allowed to be brought in, and I began to draw picture diaries. I was able to express things in drawing and writing that I could not speak freely with words, and that was the only way I could relieve stress. This painting practice that I started doing was more than a hobby to me, and I painted three picture diaries over my two years in the army. It is a special thing to express my emotions with pictures rather than words, and visualising abstract language was a great pleasure. Even today, I still refer to those paintings, but rather as a means of materialising new ideas rather than going over old daily diaries.

From the rules and regulations you were imposed throughout your education and military service to your family’s push towards Protestantism, you have grown up with certain ideological pressures. As a Protestant, male asian artist, do you question this ideal human being that has been imposed to you through your practice?

I am still asking myself this question! It is also the most central area of exploration in my work, where I analyse myself and explore how ideological enforcement has affected me. Korean society, my family background, religion and education are powerful forces so that the ‘ideal’ human image is still suppressing me, and I think that I am often following it unconsciously.

WORK

In your time as a police investigator for the Korean army, you have handled deaths, crimes and suicides, mostly spurred by mental health issues. In that sense, does your work always begin with analysing the psyche?

A lot of mental references get into my work, but this is not always the case. However, when I look over these again, I realise that there are many cases where such references do exist. It seems that such experiences in the army naturally penetrates all the work.

The ‘hand’ is a motif that you usually represent. With connotations of labour, domesticity, or political views… what draws you to explore this particular symbol?

The ‘hand’ really contains various meanings and you can find those references in all areas. I think that there are two major ways that human emotions are best expressed in the human body: one is with a face and the other is with a hand. I think that a hand reveals more indirect and also more refined feelings than a face. In my work, the hand is best explained as a medium that indirectly shows my own emotions, but nobody knows exactly what that feeling is. It is the body of the hand that represents the subtle emotion that I don’t even know of.

Elastic, wobbly and floppy, silicon is a material that you have enjoyed using for the past year. Is this associated to its skin-like qualities?

In my work, the human body analogy is habitually used. I thought a lot about what materials could best reveal human physical features and also explore the sensation of touch, and so I realised it was best to use silicon. It does not have a human warmth, but its substance and texture feel very much like human skin.

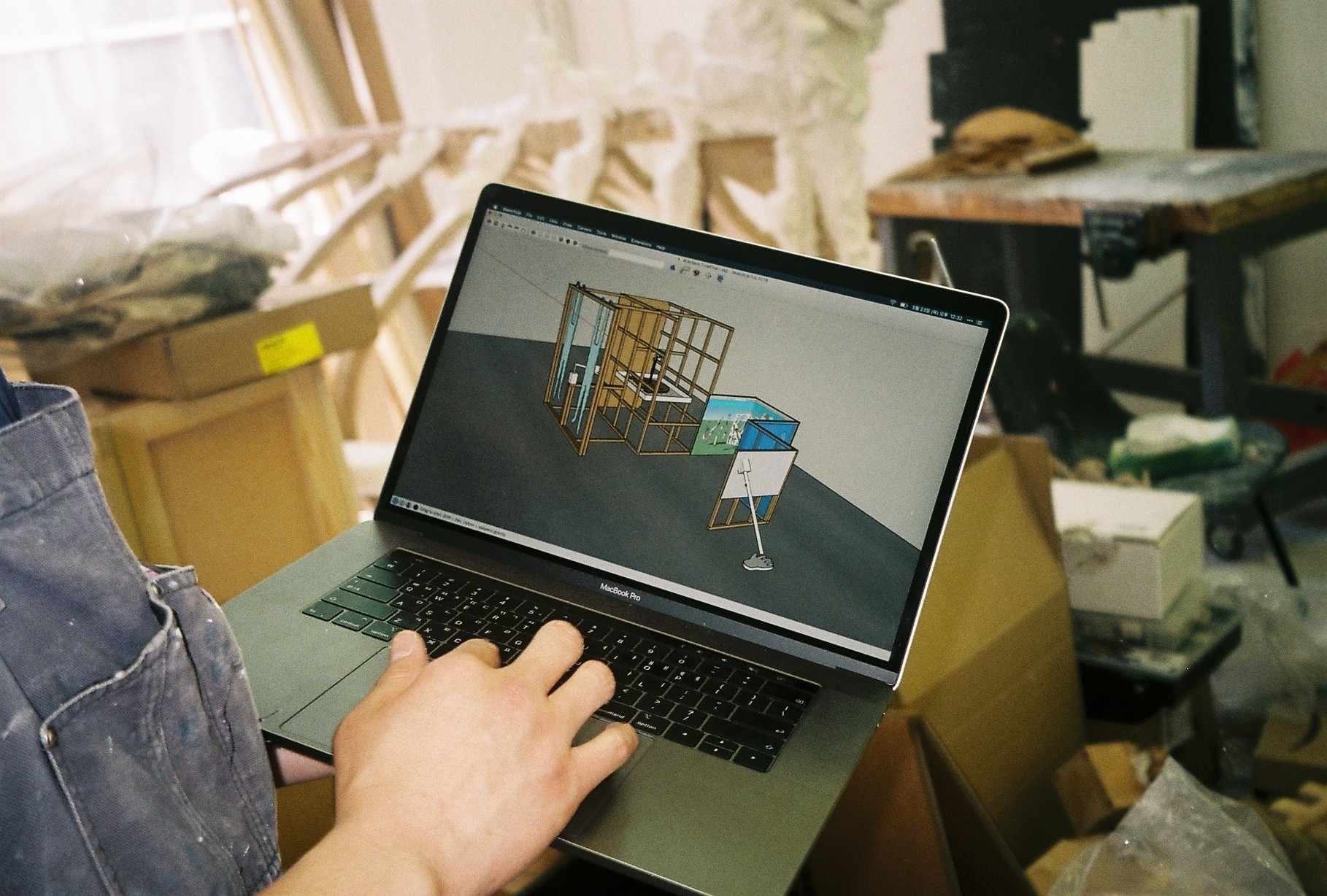

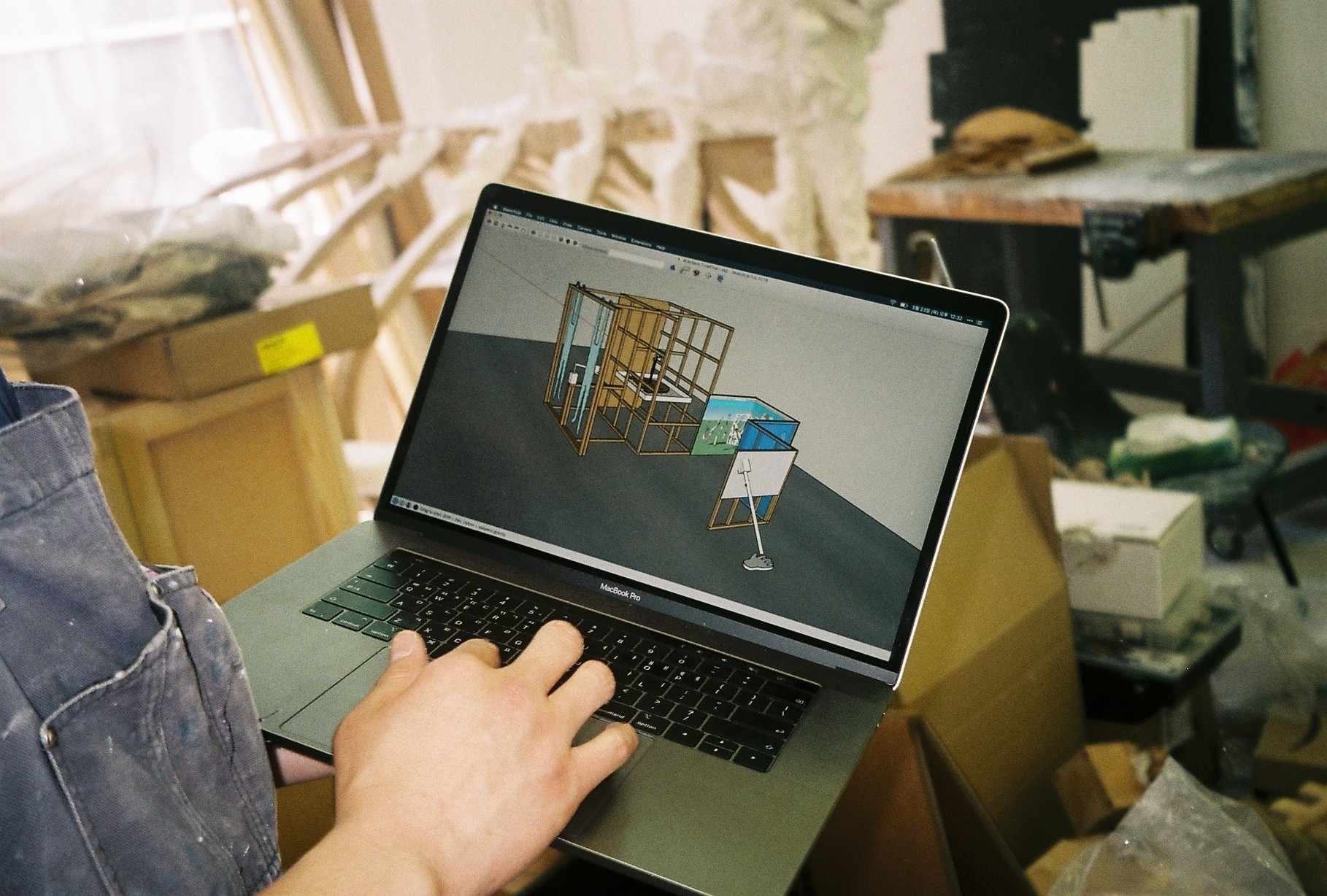

By revealing not only the silicon but it’s wooden mould in your degree show installation at the Slade, are you interested in exploring ideas of work-in-progress associated to industrial factories, and systems of production en-masse?

One of the biggest inspirations for my recent work has been the factory’s production line. I enjoy watching such videos on YouTube! I am interested in how the ready-made products I use are made and produced. When I see the moment of constantly producing the same product, it reminds me of my friends.

Can you tell me more about your use of pastel tonalities?

Since I was a child, I was obsessed with the obligation that ‘men should be men’. I was treated as a strange person when I was a little bit ‘out’ of the ideal male image which the school, army and society wanted. This ideal can be found in the social consciousness that distinguishes sex by colour. Men must recognise that they should like blue or green, and women should like pink or yellow. I think this is one of the ideological products of various political and cultural ideas. If you add white to the primary colour, it becomes a pastel tone giving a soft feeling of saturation. Such pastel tones have given me a neutral image, and it was a feeling of refuting the ‘colourism’ that I perceived.

Laborious actions of washing or most recently of getting dirty are recurrent in your practice. Do these activities, often mechanical and cyclical – with no beginning or ending, reference ideas of purification or religious aspirations?

Yes. Especially, I can find such symbolic meanings in ‘Wring me harder’ and ‘I do not want to do laundry’. The work deals with my sin, which is clearly forbidden by the Bible and can not be told to anyone. As a Christian, I think that I have committed the sin that I should not commit, but at the same time I deny that it is a sin. I wanted to reveal such dual feelings within my work by exploring if I can wash my clothes every day and watch the dirty clothes get cleaned, and therefore if my own sins can be condemned just like those laundry ones. At the same time, the impoverished laundry is forcibly washed by someone repeatedly, and this is reminiscent of the cost of the sin itself.

The silicone figures in your works seem to have no individual agency. With no faces, genders, or clothing attributes, they undertake pointless activities and are often held within a structure larger than themselves. Does this link back to your time in the army at the age of 21, where your individual existence and opinion was to a certain extent, pointless?

It is possible to read that sense of pointlessness in my sculptures. The beginning of my work always starts with something trivial from my personal story. It could be from my childhood memories, but often it is from experiences in the military, family or school, which can all be felt as large structures. However, in the end, I aim to represent all of the people who might feel like me, but who may not be of my own background or generation. So, I do not reveal anyone specifically in the work and by showing the model of an abstract person without revealing their sex, age, or race, everyone is welcome to transfer their feelings into my work.

Waves of rhythm surround your figurative characters. Can you go through the symbolic meaning attributed to these curvaceous shapes?

Recent work has a lot of psychoanalytic components in general and with this, I try to explore the vague boundaries of dreams and reality. I began researching on human brain waves and became particularly interested in Theta Waves, which is the state that the human body enters before and after sleeping. Consequently, I began to apply that waveform to my work. So, I tried to visualise that ambiguous boundary with this reference.

Cartoons often undertake exaggerated actions which are viewed as humorous within society, such as explosions or electrocutions. Do you reference this animated language by blurring the boundaries between tragedy and comedy? Is the humour element in these disasters still funny when taking them out of their cartoon setting and placing these ideas within a real, physical context?

I do not think so. Exaggerated and violent scenes in animation make people laugh, but I think it’s a very special device that is only allowed in cartoons. If such a scene is reproduced in reality, it is a tragedy, not a comedy. For example, if a person is electrocuted in real life, the person can die instantly, but in cartoons, the scene of a comic character having a bad experience with electricity will seem funny and ridiculous. But yes, I like to blur the boundaries so that there is a balance of tragic and comic energy in my work.

The installations you make are often composed of a myriad of revealed layers and elements that sustain, activate or support each other. Does that ability to see the several frames at once mirror hierarchical structures at large?

That’s right. When I was young, there was a collapse of the biggest and wealthiest department store in Seoul. The store was only five minutes away from my home, and the parents of my friends died in the accident. At that time, it was an event that showed the problems of the whole of Korean society at once. The building had been constructed very speedily and without proper investment in its safety. In fact, some of the construction workers had died during this process. Once the store had opened and then collapsed, it seemed to indiscriminately reveal the conflict that existed in the social strata, and the problems of such high-speed social growth at that time. I applied my memory of the collapsed wreckage of the department store to my abstract work.

You often stage and interconnect objects through stacking tensions, gravity escalations, and precarious compositions. Are you concerned in cause and effect situations at large?

Yes, I do think a lot about how things in life stack up against each other. I am concerned about such issues, but I tend to be brave when I organise and build my work. Otherwise, I will not be able to create my work, and it will be a big obstacle when I plan the next piece.

Roald Dahl and Louis Althusser are some of the references you pulled out in my recent studio visit. What are your favourite writers, philosophers, or cartoon characters and why?

Haruki Murakami is my favourite novelist; he is considered to be the most important figure in postmodern literature. I’ve been reading his novels since adolescence and I especially like his style of writing. His novels are very surreal, depressing, and fatalistic, and I think those elements have had a great impact on my work. Louis Althusser is a philosopher who has had the most influence on my recent work, especially his essay ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’. I have been inspired by his theory of ideology, and am still exploring this. Donald Duck is my favourite cartoon character, he was widely used as a propaganda figure during World War II and was written mostly as a satirical character. He is conscripted into the army, lives in the training camp, and enters the war. There are a series of story lines that remind me of my own military life, but there are also other things about this character and episodes in its history that I can relate to. In particular, I remembered my military life when watching that frustrated character, and I felt strong pity.

FUTURE

You’ve worked with illustration, drawing, painting, sculpture and most recently learnt kinetic engineering for your works alongside utilising TV projections, digital drawings and sound. Is your making-boundary in continuous expansion? What medium is next for you?

Yes, I try to use as many mediums as possible and the fact that there are still so many mediums that I have not covered makes me very excited. But now, I want to focus on silicon, my main ingredient. In fact, there are many kinds of silicon which I have not used yet and I still think I do not understand the materiality of silicon to its full capacity. So for the time being, I will use that material and try to develop my work with it.

14.08.19

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Shinuk Suh

Journal