Memento Mori

Let me know mine end and the number of my days, … verily, ev’ry man living is altogether vanity.

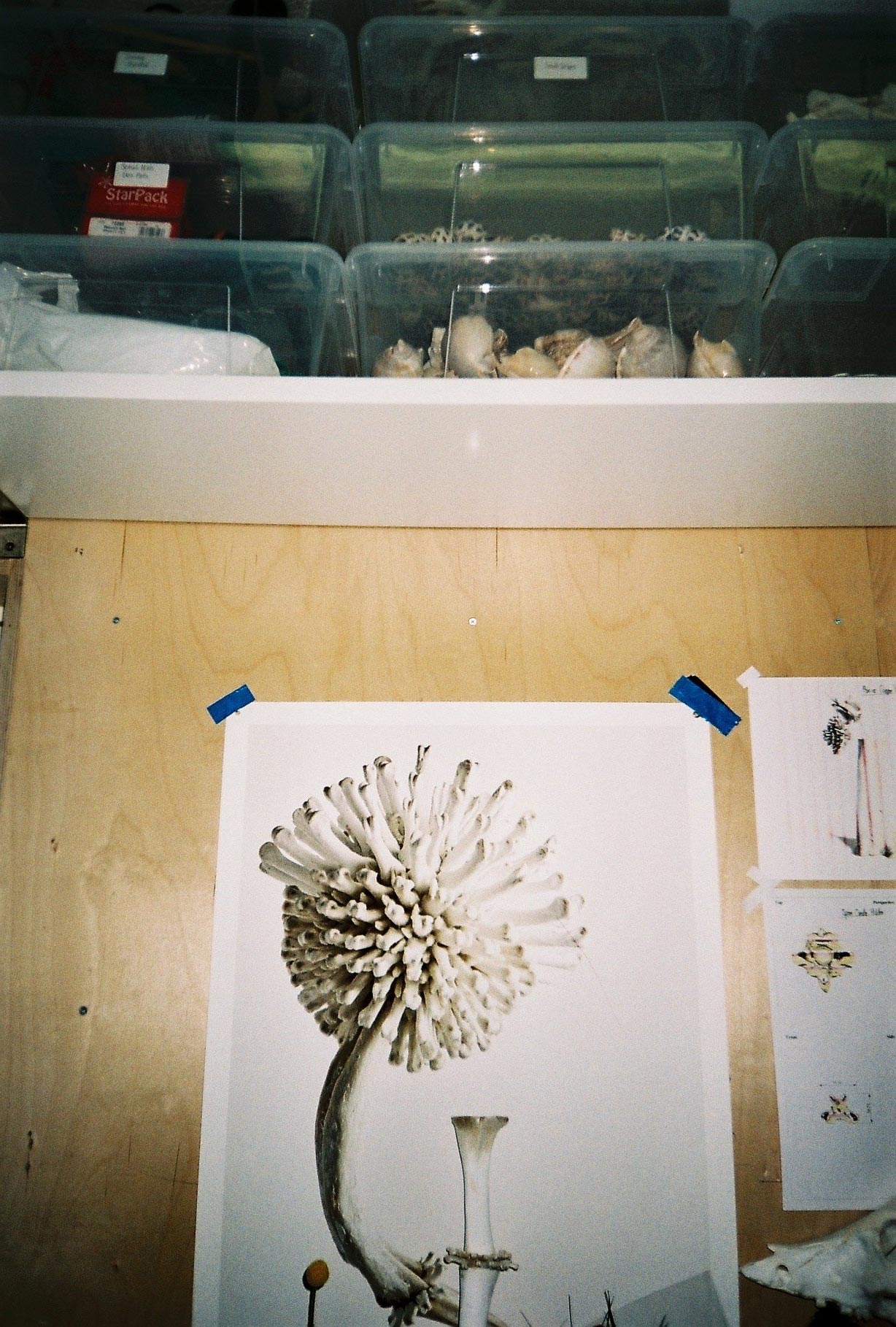

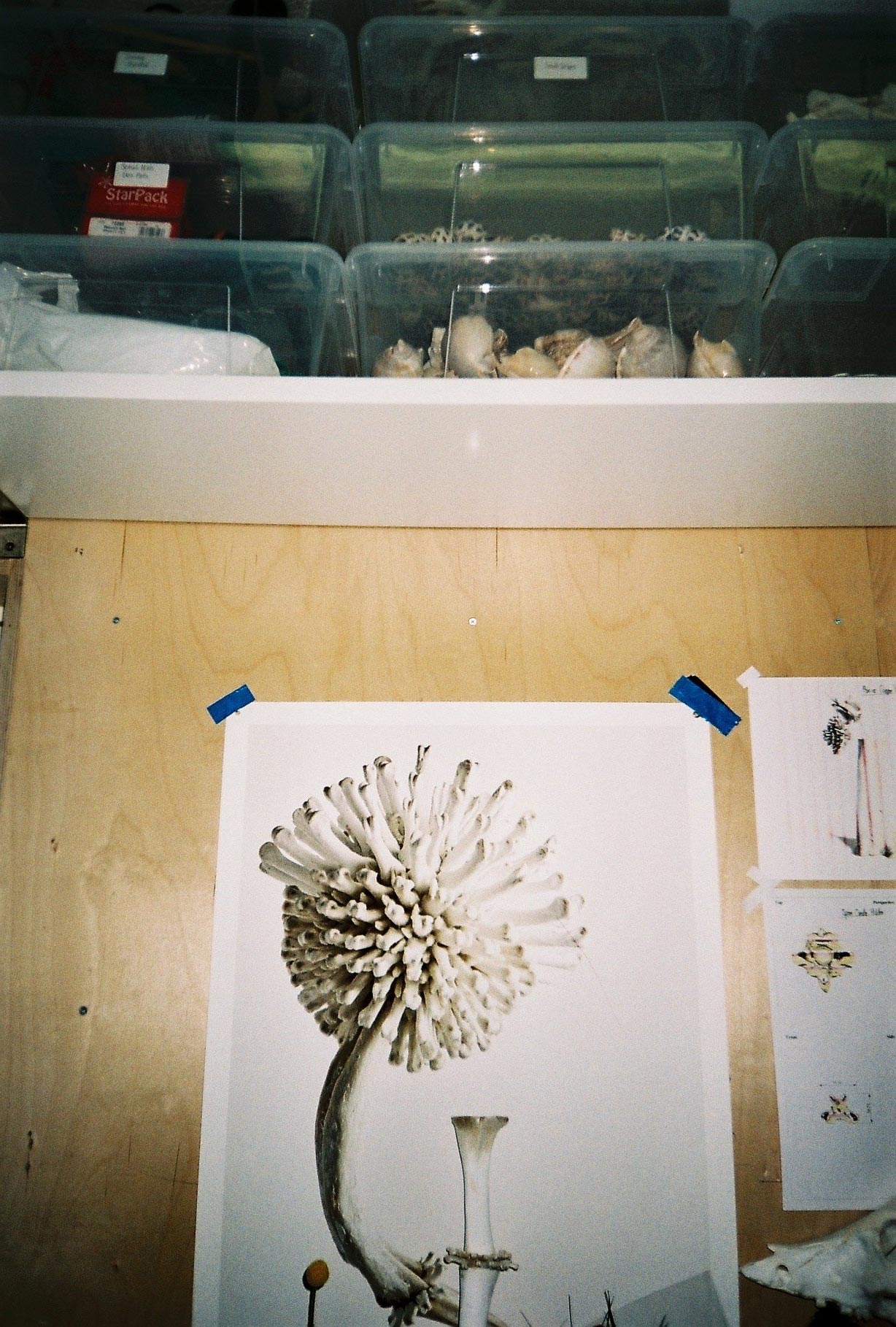

Artist Emma Witter’s studio is full of bones. There are bones scattered on the desk, pictures of bones on the walls, boxes of bones on the shelves. Some of these bones are sorted into types and categories – there is a box of jaws, complete with teeth. Another box is bathetically labelled disasters. In other places, the bones have been combined in ways that make them unrecognisable to the lay person, perhaps chicken legs combined with pigs’ knuckles and cows’ ribs. I hold a turkey’s vertebrae in my hand and exclaim over how large and smooth it is, before being told that it is an enlarged 3D-printed model of the original.

Self-taught in bone craft, Emma Witter cleans and bleaches animal bones through a complex procedure of soaking, washing and drying. The process of working with the bones is ritualistic, reminiscent of traditional practices around death and the preparation of bodies for the grave. I am reminded of a Japanese funerary rite, in which family members use chopsticks to pick fragments of charred bone from the cremated remains of a loved one.

The leg bone’s connected to the…

The respectful and practical death traditions sometimes found in other cultures are a reminder of just how separated we are from death in the West. But this separation is relatively recent. Like so many other things that now define how we live – fossil-fuel reliance, the practical and ideological separation of humans from animals, capitalist market forces, urbanisation, antibacterial disinfectant – our contemporary division between ourselves and our dead stems from the era of the industrial revolution.

During this period of immense change, many of the tasks which had previously been done by women as part of the invisible labour of the home were commercialised – almost always by men. Such was the case with death and dying. In most families in the pre-industrial era, women would have cared for the dying in the home, and they would have washed and dressed the corpses of family members, preparing them for burial. A dead body would have been kept in the house while funerary arrangements were being made.

But in the Victorian era (a period we often associate with the macabre) men made an exclusive career of something that was once a matter of course. They built funeral parlours and mortuaries, acted as middlemen for coffin builders and stone cutters, and encouraged the rising middle classes to believe that dead bodies are something to be feared in both psychological and physiological terms. They took the communal, ritualistic, practical actions of women in the home, and transformed death into an industry in which their own position was unimpeachable, inaccessible, backed by science.

Et in Arcadia ego…

In some ways, Emma Witter’s practice reasserts the feminine and domestic aspects of death and funerary rites, while also drawing on centuries of art historical tradition. She transforms the bones she collects into sculptural flowers and organic shapes, creating a fluid conceptual shift between animal and plant matter. There is also a slippage between art, craft and design at play here. The flowers have both an air of accessibility and a whiff of the decorative about them, echoing feminist debates over the status of ‘women’s work’ in the capitalist, androcentric system created by Western patriarchal values.

Witter’s work could be connected conceptually with the ‘death positive’ movement, which encourages us to feel that human curiosity about death is natural rather than morbid, and which is overwhelmingly led by women. These morticians, artists, anthropologists and therapists ask us to reassess the death practices that once belonged to the realm of the domestic and to the unpaid labour of women, looking beyond the sanitisation and professionalisation of death created by mid-19th century capitalist impulses.

For all flesh is as grass, and all the glory of man as the flower of grass. The grass withereth, and the flower thereof falleth away.

While the imagery of flowers is typically associated with women, there is also a long art historical tradition of presenting flowers as a symbol of death, either alongside images of bones or as a stand-in for the skull in vanitas paintings. Cut flowers – their vitality and beauty flourishing despite being severed from their roots – present an uneasy ambiguity, hovering between exuberant life and inevitable death. Works from the golden age of Dutch still life painting depict vases of flowers at that uneasy moment between their sensuous peak and the inescapable drooping of their petals that follows soon afterwards. Remember, these paintings tell us, that you will die.

In many religious traditions, death imagery is intended to remind us to live a blameless, devout life, in order to gain the rewards of the life to come and to avoid its punishments. However, the feminist perspective might be to accept the inevitability of death, and that curiosity about this fact is both normal and acceptable.

Emma Witter’s bone-flowers provide an access point to conversations about death – both our own future demise and the deaths of the animals whose bones have been used to make the works. Witter challenges the stigma around such conversations and opens them up through beauty and a spiralling network of associated topical and timeless issues, from vegetarianism to feminism to capitalism.

Dem bones, dem bones gonna walk around.

Dem bones, dem bones gonna walk around.

Dem bones, dem bones gonna walk around.

Emma Witter: Remember You Must Die is on view at the Sarabande Foundation from Thursday 19 September until Saturday 22 September 2019. For more information, visit here.

04.09.19

Words by Anna Souter

Related

Journal

Rodrigo Arteaga

Journal