Between the functional and the aestheticised.

For her latest project, Italian artist Bea Bonafini has transformed the Zabludowicz Invites space into a proposal for a non-religious chapel. In this interview, she discusses her process and ideas behind her work, and how her environment, Matisse, the Sienna Cathedral, the Memphis group, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Marc-Camille Chaimowicz have influenced her practice.

BACKGROUND

How and why did you widen your artistic approach and when did you expand your practice to incorporate other mediums?

I began my Art Foundation course as a painter. I had a really difficult time with some of the tutors who made me feel uncomfortable with painting. So, I tried to find other ways to express myself, and ended up doing a lot of sculptures with different materials, and eventually also performances. For my BA I went to the Slade School of Fine Art, which is a nurturing place for painters, and I stayed in the painting department for four years. My relationship to painting grew more and more uncomfortable, so by my third year I began collaborating full-time with my best friend and artist, Cecilia Granara. We felt the urgency to paint our own bodies and do something that was very much alive, making performances felt right. In some ways it was an extension of painting. I no longer felt stuck. It opened up a world for me, I used mixed materials for costumes, which then turned into sculptures. Painting always stayed in my mind, and has always been a reference point. When Cecilia left London at the end of that year, I went back to an individual practice. I began working much more with fabrics, sewing them and stretching them back over canvases, using the language of paintings.

You create many textile-based objects, although your academic background is mostly based on painting. What has inspired you about this medium, about textiles?

When Matisse became too ill to paint in his late sixties, he began cutting painted paper and making collages. At the end of my third year when Cecilia left, I was diagnosed with lymphoma. I felt that at that point of my life, my materials adapted to what I was going through. I no longer forced myself to make traditional paintings. Cutting directly into fabrics, sewing them back together, layering them, making collages, whilst maintaining a dialogue with painting, felt really powerful for me. I saw fabric as sheets of paint that were ready, clear and defined. The images I created at that time were quite strong and graphic, there were a lot of severed heads. I guess there was a violence to the cutting and the sewing that felt appropriate.

You describe yourself as having a very ‘nomadic upbringing’. Having lived in in Perth, Rome, Dublin, Bratislava, and now London, you have been confronted to different cultural backgrounds. Could you tell us more about these experiences? To what extent your many travels and residencies have influenced your practice?

Moving country every four years meant that my heart was broken every time I left my friends behind and went into unfamiliar environments with unfamiliar languages and unfamiliar people. I was always the new kid at school who didn’t know the other kids’ way of life and didn’t speak their language. I became used to unfamiliarity and being the outsider. I think that influenced the way I work; travel gives me inspiration, I need to be in unfamiliar environments, and I jump around a lot with the mediums I use. If I stick to one process or material for too long, I start feeling restless. Perhaps due to a mix of character and upbringing, I need to feel constantly surprised by my work; things need to be experimental, and I think residencies and other travels helps.

Since you use various colours and a variety of mediums, how do you find a unity in your practice?

I like working on several pieces at the same time in my studio, so I’m not stuck with one process. Often one work might require a physically exhausting process, and having several works with different approaches means I can balance it out. The works can then interact, which is something I really enjoy. Things start to leek from one work to another, and they start sharing languages that are not forced on them from the beginning. For example, something that is made in wood might have the same kind of language as something that is made in pencil, a certain kind of shape may start reoccurring. Because they cohabit the same space, they start creating mutual codes.

PROCESS

You still continue to draw in order to fuel your artistic research. What is the role of your drawings in your current practice?

Drawing is indispensable for me to understand something conceptually. When I am drawn to something, I tend to draw it over and over again to figure out what it is about that thing that attracts me. Once I start developing a more specific project, drawing helps me understand how to make it technically. I have many sketchbooks that are private. I don’t think about composition, the pages aren’t thought out, they are just notes and sketches. Since my residency at Villa Lena in Italy in October-November 2016, I started making drawings in sections, that can be transported easily. I want to be able to travel and make large-scale work, and one way to do this is to work on paper tiles that can fit in a suitcase, and then reconfigure them when I am back in the studio. I like the idea of the tile because it goes back to the way I use textiles in sections that are then sewn back together. It also means that I can travel for a month and do my own self-appointed residency, and then come back and show a large-scale piece.

Colours are crucial in your practice. What leads you to use a particular colour range? Is there any symbolism behind your choices?

It depends. For my Slade degree show, I used very bold colours. The entire room was a strong lobster red that I was obsessed with at the time, and many of the works had the same tones, so the pieces disappeared and appeared in the room. The red came from my travels with Cecilia in India. It is a colour that is used a lot in temples, rituals, festivals and so on. It is also quite a violent colour. In other cases, I am influenced by my environment. For the recent carpet piece and drawing for Zabludowicz Invites, the setting of my studio influenced the tonalities of blues, greens, and greys, as I work in something like a tree house.

You are experimenting with materials to create artworks, and you mention that they can ‘influence each other’. In this process making, there is this idea of constantly living. When do you consider that an artwork is finished – ready to be displayed?

I go a lot by instinct, but also by deadlines. Deadlines for shows give me a sense of urgency, which means I end up finishing a piece just because I have to. A lot of the time I feel like something is ready when it gives me a bit of a thrill, and when the work has personality, somehow.

Your practice is very much a reflection on the limits of design. What is the relationship between design, high fashion, and architecture in your artwork?

I have looked at Memphis, the Italian design and architecture collective from the eighties, but also at artists such as Marc-Camille Chaimowicz. In both, I am drawn to how they fill gaps between categories. Memphis is design-based and focuses on interior domestic spaces, but their interiors could very well be installations in an art gallery. Chaimowicz’s practice is for the gallery space, things are less functional, or they look more like theatre sets. Both create installations that you step into, spaces where the objects belong to a coherent language, nothing is out of place, it is all adhering to one concept.

CURRENT EXHIBITION

‘Dovetail’s Nest’ at the Zabludowicz Collection includes a large inlaid carpet work that covers the entire floor of the gallery. Its design has been inspired by a 15th Century marble floor piece from the Siena Duomo. Could you tell us more about your experience at the Siena Duomo, and how it has influenced your work?

I first encountered the Siena cathedral in November 2016 while on my Villa Lena residency. Over there, all the artists resided in a former noble country villa in the middle of nowhere. It is a spectacular building that has been kept much as it was originally, and has different frescoes and patterned tiles in each room. The tiles created optical illusions, they were very similar to the ones in the Siena cathedral floors. The cathedral also has dozens of incredible narrative marble inlays, which are made in sections of marble with engraved details. There was one particular battle scene which had been abstracted as footfall smoothed the stones, erasing the details. Usually they restore them every so often, but this one had been left consumed. It reminded me of my fabric pieces in the way that it sat between figuration and abstraction, was like a puzzle piece, and was quite theatrical in its depiction of an otherwise violent scene.

Does the idea of a marble floor with details that have been erased due to the numerous footfall echo the idea of an artwork constantly living?

Yes, definitely. This is an interior space that is used daily over centuries, and has a function. An image being erased by passers-by is a way for an artwork to keep on actively living. I always have in mind the approachability of an artwork in an art space. In most art spaces you are never allowed to touch anything, I like to touch artworks while the invigilators aren’t watching. I can see that the artist’s hands have been all over it; I want to touch it to understand it better. I think that when an artwork has the option of becoming functional or being walked on, there is the risk of it getting worn, that it will change, that it is susceptible to transformation, rather than it being preserved, intact.

The term ‘dovetail’ means ‘fit together and harmonic’ although your work maintains itself in between the functional and the aestheticised, where softness juxtaposes with hardness, interior and exterior, comfort and conflict, or heaviness with lightness. Are you concerned in achieving a harmonic balance in your work? To what point do you want to test the notion of comfort?

Yes and no. I think a lot about the way in which chapels are seductive, how you want to spend time in them, to contemplate or to pray, although they are packed with imagery. Many of the artworks in there are very beautiful, seductive, and pleasing, so you want to stay; but underneath these layers of decoration and art, you have the idea of indoctrination, propaganda, being sold a belief, and a lot of them are quite violent scenes. I often think about the amount of time that people spend inside a Church, surrounded by all that violence. I guess what I am trying to achieve in my work is a similar thing – I want you to spend time with it. Things may be tactile or soft. Because they can be functional, it means that you can actually use them, and therefore spend time with them. But also I want there to be some sense of discomfort; perhaps the coffee table you are using is too delicate for you to be relaxed around it, so as you put a drink on it, you are terrified. This idea of walking across a carpet and slowly absorbing imagery is inherently a bit traumatic. I like to think of spaces such as the home as being a space of ultimate comfort. But in the end you things don’t work, or the relationship dynamics of the people living in there might be off; there are many reasons why a house might not be the most comfortable place. In the same way, there are these little ‘off’ things that you start to absorb when you spend time with the work.

You also present a large drawing on paper displayed in the form of an altarpiece. Could you describe its narrative, and its position in the installation?

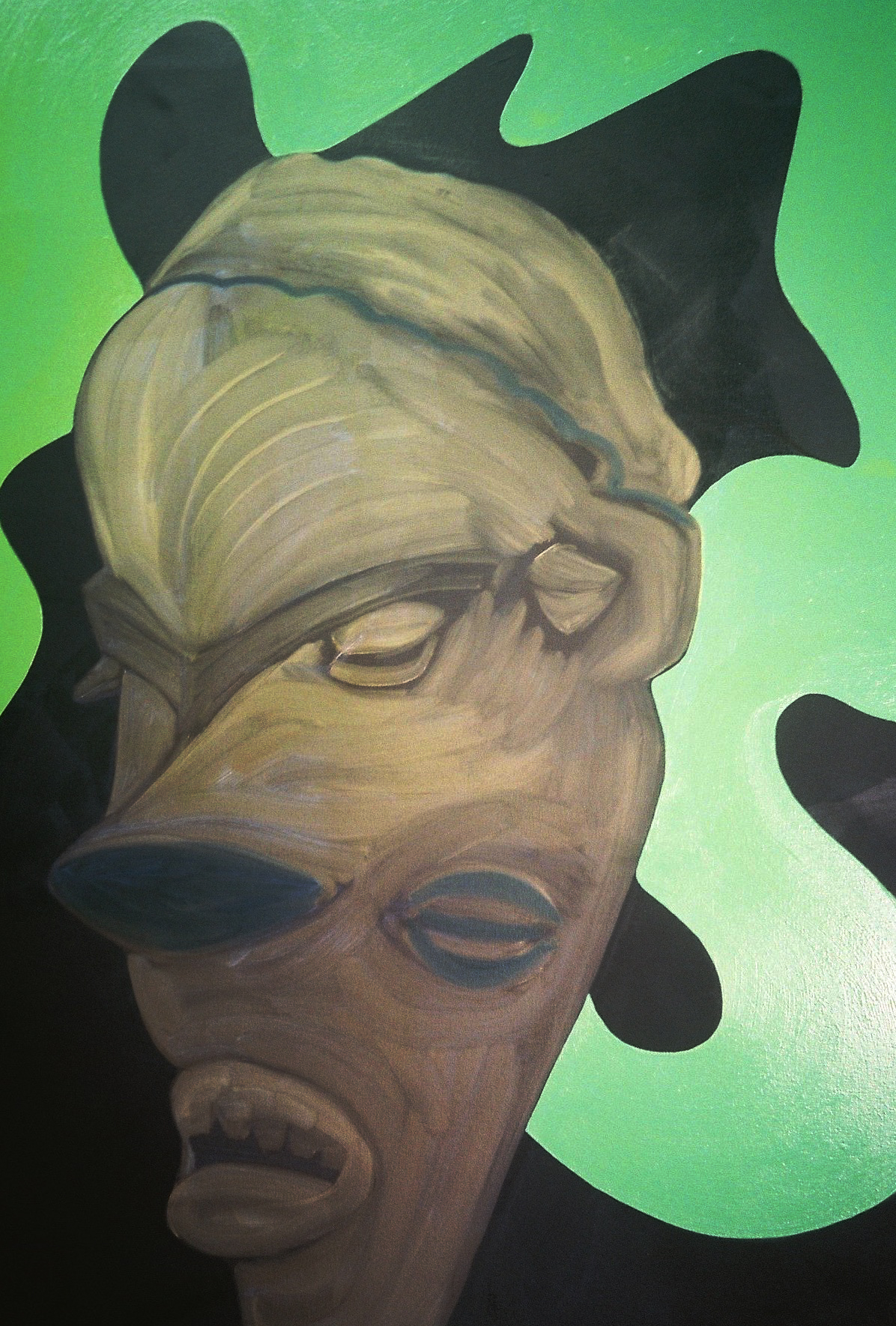

I am looking at deconsecrated as well as religious chapels for this project. Alterpieces act as a magnet pulling you through the space, they are an end point. The Invites space is very chapel-like, and you can see the far end wall from the entrance. I wanted there to be something on the opposite end of the room that pulls you through, and makes you walk across the carpet in order to reach it. The colours of the drawing are quite subtle, so you can’t see the details until you really get up close to it. The subject is a proposition for a non-religious chapel. It is the second in its series, and it isn’t necessarily narrative. It is a space where nothing is really “happening”, and yet everything happens in terms of architecture, pattern, shadows, light, and form. It is a space for contemplation and thought, that doesn’t adhere to a specific belief. It isn’t trying to indoctrinate whoever is in it. There are three very tall totemic sculptures which are similar to some of my previous work. The height of most churches allows for frescoes on ceilings, or very tall sculptures; in temples too, you have sculptures of deities that are larger than human size. These force us to look upwards, reminding us of how small we and our problems really are. I was also thinking of how fewer and fewer churches are being built nowadays, how younger generations are becoming more distant from religion, at least in Italy or in the UK. In a way, churches are being replaced by exhibition spaces. But the exhibition space does something very different; the space in this drawing lies somewhere in between the two.

How important is it for you that the viewer participates in your work?

Sometimes it is essential. In my series of Banquet Performances, the participation of the viewer is paramount to the dining experience. You can’t start the dinner if one place is empty. In my previous installations in coffee spaces, for example, I took over a space that had an ideology and a function, and the works were furniture-based. It was interesting to see the space both populated and not. When the sofas or coffee tables weren’t in use, they became more like an installation to be observed. As soon they were used, it started breaking boundaries and that’s when different dynamics started happening. For Invites, it really isn’t asking for much participation other than asking people to walk on the work, and to remove their shoes. The participation is the act of standing on the work, feeling it or sitting on it. It is essential to walk over the floor in order to enter the space.

FUTURE

One of your long-term projects is to create “La Bocca”, a living house installation. Can you tell us more about this project?

I want to integrating art into domestic life more and more. The work I am making now is very much about the domestic, the functional and the dysfunctional. I want to create a space that is not temporary, but a place where objects accumulate over time; where I can invite artists to affect the space with their own artistic sensitivities, so that in each room there is different story. It should be in the countryside, where I thrive. The city can be very difficult. I am really lucky right now to have been given a studio residency at Fieldworks Studios. La Bocca will hopefully be a space that can act as a living, growing installation. A big inspiration for this is Niki de Saint Phalle’s ‘Tarot Garden’. When I saw it at the age of 16, I knew I wanted to do something of my own along those lines. As soon as you enter the gates, you are in her world. There are sculptures which you look at, walk around or climb on, such as the courtyard and balconies, and even a house-sculpture. It is a very extensive project, and I am aware that La Bocca would be much smaller due to funds. It is something that will happen eventually with my community of friends and artists.

Do have any future plans, projects or collaborations in mind?

I have been co-producing Fibra art residency with curator Mia Pfeifer. It will take place in Colombia with a selection of ten artists, including Adeline de Monseignat, Jonathan Trayte, Jonathan Baldock and Nika Neelova, amongst others. Mia and I are both passionate about textiles, and Mia is Colombian, she has a very strong attachment to the country, having left at 18. Colombia has a strong tradition of traditional textile works. The residency returns to roots and traditions, allowing us to learn from two indigenous tribes, to bring back the skills and knowledge and incorporate it in our practices. My next banquet performance will be at Guest Project Space in August 2017, and is curated by Isabel Blanco Fernandez. Over the course of the day the public will be invited to participate in a pasta and crockery-making workshop; at the end of the day we will cook all the pasta, and have a huge feast on long communal tables.

13.06.17

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Bea Bonafini

Interview