When material meets concept: British artist Arthur Laidlaw examines the interrelation of ‘subject’ and ‘matter’.

It’s been eight months since I first met artist Arthur Laidlaw at East of Elsewhere in Berlin, who at the time, showed me around one of his most ambitious works to date: a site-specific cardboard installation on the limits between art and architecture, that dominated the entire living room of the domestic space. This work explored a first-hand criticism towards the undervalued status of Berlin’s Spätkauf, a convenience store open throughout the night which the artist describes as “an essential part of the fabric of the city, but dwarfed by the architectural landmarks of historical significance in Berlin”. He therefore remarked this statement through the use of an undervalued and under-appreciated artistic medium such as cardboard, which is often proved as being too ephemeral to work with. What sets Athur’s practice in distinction is how interrelated his materials are with the subjects he explores. Last year, he participated in ‘Where Are We Now?’, a solo exhibition at Vadaxoglou, London, in which he inspected the Grenfell Tower fire tragedy through the employment of charcoal works, an appropriate use of material, considering it is composed by ash residue. It is no surprise that with his choice of mediums, the artist directs the viewers into the content of the work. This week, I find myself in Laidlaw’s South Bermondsey based studio, prior to his permanent move to Berlin, a city which is embedded by it’s own history through it’s the architecture, and a place that has allowed the artist to engage further with today’s European political climate. Here, we discuss how he will continue to trace the roots of classical civilisation through his works, why ignorance has driven him into curiosity and the ways in which his layered works merge both distorted memories and history.

BACKGROUND

You graduated from a History of Art BA at Oxford University and then transitioned to Fine Art with an MA at City & Guilds. How has your art history background fed into your artistic practice and vice-versa?

To begin with, I found my History of Art degree a little paralysing; as I started work as a practicing artist, I second-guessed myself regularly, jumping ahead to the consequences and ramifications of my material and conceptual choices. The further I get from it, however, the more helpful it becomes. Perhaps the most helpful thing was that it emphasised was how little I knew about art and its history, and how important ignorance can be. When you’re honest about your own lack of knowledge or understanding of a subject, ignorance can drive curiosity. This curiosity is the basis for asking a question again and again, from different perspectives, each time reaching a fractionally different result. From a compositional, curatorial point of view, my History of Art degree also taught me how to structure an argument. This has become invaluable both in the individual setting out of an image, and also the planning of an exhibition.

Your mum is a former graphic-designer, now practicing painter. Do you both dialogue and support each other’s work?

We try to – she is my most honest and fair critic. That criticism can be hard to receive occasionally, but it’s almost always well founded. She is also my biggest artistic support, and I try to return that support whenever I can – though it’s hard to imagine how I’ll be able to repay her for everything she’s helped with over the years.

Do you think that your formal training as an artist enables you a certain level of confidence in your work? How important is this confidence to delve into the ‘art world’ and its challenges?

Strangely, it’s the degree in art history that helps me most here. I think the knowledge of your own fallibility gives you confidence. It’s a constant reminder not to be too ambitious each day, and instead simply try to be true to your own life experience – and hopefully the quality of the work will follow.

WORK

Is narrative a big part of what you do?

Yes, narrative is an essential part of my practice. I believe in artwork as a kind of communicative tool to express an event or idea, or even an entire Weltanschauung. That is not to say there must be a fixed beginning, middle, or end – the structure and form of my work and exhibitions is looser than that – but there must be somewhere for the viewer to begin to relate the image to themselves, and their own life experiences. This relationship, between the perspective from which an artwork is produced and the viewer’s own, is valuable as a tool for teaching and practicing empathy. It forces a confrontation and resolution of different opinions in a world of increasing division and encouraged partisanship.

Documenting Syria through analogue photography was a starting point for you to deal with this medium. Can you go through your process of reworking these photographs, and how your re-contextualisation of the medium paralleled with your distorted view of the country?

As I moved further away from my original journey around the Mediterranean and the Middle East, in 2009, it became harder to reconcile my experiences with the news from Syria and many of the surrounding countries. The 4000 or so photographs I took were taken as ‘honest’ representations of the objects I saw and the places I visited, but they assumed new, unintended meaning over the next seven years. I believe that some of the universally-felt sense of loss, in reaction to the destruction of Syria’s ancient monuments, can be traced to the classical language of architecture, which many ‘Western’ countries have adopted for imperial ambitions. Almost every street you walk down in London is likely to have a classical moulding across its facade, a mock-pediment over its windows, or a faux-portico surrounding its doorway. The aesthetic of classicism has, consciously or not, become the (stolen) aesthetic of much of the ‘Western’ world—and therefore the destruction of its origins feels somehow personal.

In what ways do you reinterpret your own memories of a place through a layered work production?

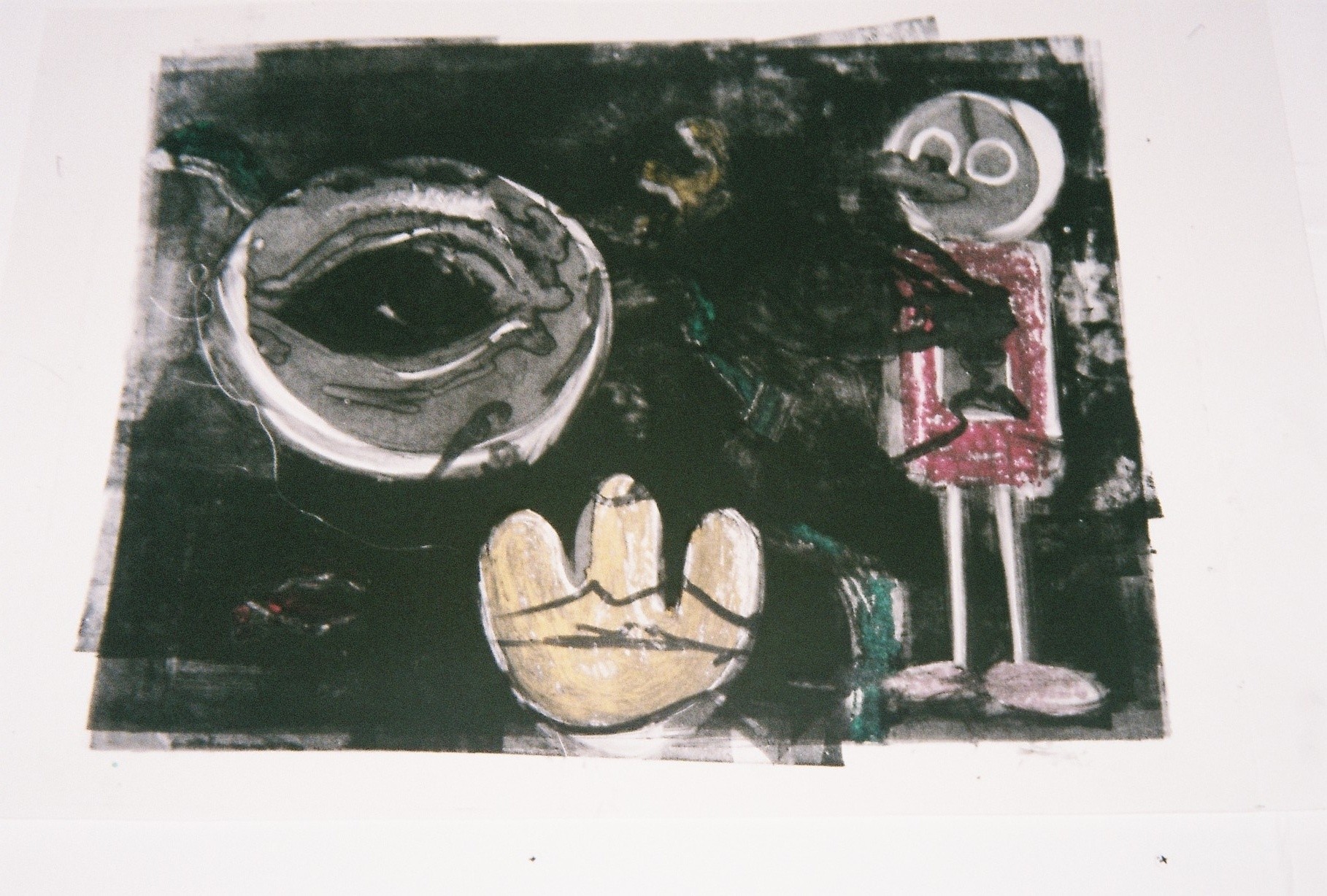

I slowly developed a method for working onto the surface of the image, which involved obscuring the photograph, and layering different processes onto the picture-plane, until it became difficult to tell where the actual object ends and the distorted memory begins. In my 2016 exhibition at the Oxo Tower, ‘Razed: Syrian Ruins’, I showed five photographs ‘simply’ as photos. The twenty remaining works began as photographs, and were then masked by tape, obscured by painting, and eventually drawn onto using a mono-printing process. This process involves drawing from memory onto a black plastic sheet covering the photograph; the pencil pushes black lines of etching ink on the back of the sheet onto the surface of the already distorted image. The layers reference the decay and destruction of the subject, but refer also to our own ever-evolving, prejudicial memories. The work examines this gap, between a lived experience of a place, and a fragile, fading memory that gets pushed around by the narratives of politicians, newspapers, and countless other self-interested forces.

You recently responded to the one-year anniversary of the Grenfell tower incident through a series of charcoal drawings of UK’s council estates. Can you explain us this project further? Did your choice of material resonate with the concept of the project?

This project is an ongoing one, aiming simply to look at the dozens of tower blocks in London that sit in the long shadow of Grenfell. The landscapes in which these buildings sit are rendered primarily in charcoal and pencil, in the hope that the simplicity of the medium may continue to direct the viewer towards the subject itself. The drawings began in London, with some of the most recognisable and threatened structures, and expanded to include towers throughout the UK. The Grenfell Tower fire was the deadliest residential fire in the UK since the Second World War; it must be understood as a warning, to prevent such a tragedy from ever happening again.

You seem to be interested in giving the audience an opportunity to access your ideas, being this through monoprints, linocuts, etchings, maquettes, graphic illustrations, videos, or site-responsive installations. In what ways do you adapt and fit your materials, tone, and aesthetic to the ideas of your work?

The idea usually comes first, or the obsession with a particular question. The communication of that idea comes next, and this is what drives the visual, physical element of my practice. For example, the Razed project was an attempt to subvert our assumed understanding of the photographic medium through layers of painting and printmaking. The Fassaden project used distorted images of the sketchbook – scanned, blown up, and painted onto – as a way of referencing both Hannah Arendt’s “banality of evil” and the endless Stasi surveillance records, subjects both in the foreground and background of these works. The Spätkauf project made use of cardboard – an overlooked medium in the canon of art history – as a way of reexamining the Spätkauf itself, a historically undervalued but societally essential building in post-war Berlin. As mentioned above, the Grenfell Tower project was a simple series of observational drawings made in situ, in a material whose connotations could not have been clearer.

“I’m just a product of my generation” was a highlight you mentioned in our recent conversation. Can you explain us this quote further?

I believe this may have been in reference to my technical and material curiosities as an artist working today. Many people of my age (I was born 1990) are somewhat trapped between a pre-internet age – characterised by an intense nostalgia – and a feeling of deep cynicism related to what has happened in the years since. Of course, each generation experiences their own chronologically specific loss of innocence, but I think that feeling has been unprecedentedly heightened by the paradigmatic shift in communicating with one and other that the internet set in motion. As such, I am obsessed by the convergence (and the frequent dissonance) of old and new technologies. For example, the process of mono-printing – a technique hundreds of years old – onto a photo-lithographic print (a process which is itself a conflation of old and new printmaking techniques) echoes the subject of my work: our relationship with the past through its remnant man-made structures.

During six months, you were unable to walk given a strong injury in your knees. In what ways did your physical limitations at the time reflect onto your work?

Only one knee – it wasn’t that serious. But yes, professionally, it brought me to a pretty immediate halt. I was moving studios, which didn’t help, and the whole thing highlighted how important physicality is to my work (and the work of most visual artists). It led to some of my smallest work – a group of lino cuts relating to the borderlands between India and Nepal, based on photographs I took the year before. Eventually, it also led to my largest work: a life size shop made out of cardboard boxes, collected from the same shops my sculpture depicted. Looking back, the desire to do something on this scale was at least in part driven by my desire to make something physically demanding, now that I was able to do so again.

I visited your Cardboard Späti work at East of Elsewhere, during the Gallery Weekend in Berlin. This piece struck me due to its temporal yet monumental qualities, along with its subject: an everyday shop. What interests you about this subject in particular?

First, it might be helpful for me to describe a Spätkauf. It is a kind of newsagent, off- license, and community hub, specific to Berlin. These small shops originated in the GDR to provide food and drink to workers after late-night shifts, and they continue to be largely operated by the Turkish or Vietnamese populations in Berlin, each of whom occupied the majority of Berlin’s manufacturing jobs throughout the second half of the 20th century. The material evolved out of a series of drawings and photographs made, with the Spätkauf as their subject. I began to work on several small cardboard maquettes of the same buildings, made using only the sketches as references. Cardboard allowed a flexibility and immediacy that I enjoyed, but my primary reason for choosing cardboard was that the material itself could be sourced from the very buildings it was then used to represent. Cardboard is undervalued and under-appreciated as an artistic medium; its ephemerality makes it unsuitable for long lasting sculpture. This echoed the undervalued status of Berlin’s Spätkauf: an essential part of the fabric of the city, but dwarfed by the architectural landmarks of ‘historical significance’ in Berlin. However, just as remains of St Thomas Kirche are a way of accessing the events of the Second World War, the Spätkauf has its own history, specific to the turbulent demographic shifts of Berlin’s history.

What leads you to examine buildings with such urgency?

In the case of the Spätkauf, global consumerist attitudes may make the lifetime of such a business a short one. Other western cultures have pushed independently owned and operated shops to the margins, with the rise of the shopping mall in America, or large supermarket chains in the UK. In the case of my subjects more generally, I think that urgency is informed by my trip to Syria and its surrounding countries in 2009. My aim was to trace the roots of classical civilisation, through drawing and photographing its extant architectural forms. Many of those structures, which I had assumed would survive another two thousand years at least, no longer exist, or are unrecognisable today. This complacency – a kind of arrogance born out of historical egocentrism – is something I do not wish to repeat. It has led indirectly to my examination of each new subject with urgency, in the knowledge that it may dissolve and be lost to history tomorrow.

In my recent studio visit, we spoke about photography and its associations of being an ‘honest’ and ‘truthful’ medium. How do you play with these notions?

Razed was an attempt at undoing the perceived solidity and factual nature of photographs. Photographs (especially our own) help us to build concrete histories of ourselves; they help to create our own narratives, even when our actions are in the distant past.

Aside of your artistic practice, you are also involved with East of Elsewhere. How does this affect your work? Do you think about the overall/wider picture more when making your work, instead of the individual pieces?

Curation is closely linked with my practice; when working on a new project, I am as concerned with how it will be presented and exhibited as I am with the internal workings of the composition. East of Elsewhere has changed my understanding of how different artists work, and the roll of a project space or gallery; it demonstrated to me how a group of people – with different perspectives and expertise – can help bring a project to life. This sometimes meant breathing new enthusiasm into a project, or pushing things gently in a new direction, but always underlined the importance of the people involved. It also changed the way I understood the reception and engagement of work; we inhabited 24/7, and organised a programme of different events, which prompted a huge range of reactions and responses from viewers. It highlighted the need for curatorial reframing as a tool, helping people to access underlying ideas in the work on display.

FUTURE

I caught up with you in a transitional state in your career, given you were getting ready to move permanently to Berlin. Why is it the time now for you to start work and life in Berlin? What will be your entry point of work there?

I left London for Berlin in an attempt to better understand Europe’s political climate. History is etched into the buildings of Berlin; examining them, it is impossible not to engage with the status of Europe today.

You mainly work in monochromatic tonalities. What will be the role of colour in your upcoming works?

I am working on the gradual reintroduction of colour in my new work. In many ways, it serves the same, layered function as other stages of the production process. However, by working in a variant three-colour monoprinting, tertiary colours emerge, and there is an introduction not only of chromatic change, but serendipity.

Your work enables conversations around politics, architecture, economy, social structures, amongst others… How do you plan to move these discussions forward through your practice?

The dialogue between each of these themes is important to me, yes. Trying to develop the relationship between a specific historical moment and our current economic or social positions has led my work and my practice in several different directions. Currently, I am working with an old German Super 8 camera, but breaking down each video frame by frame to scan, print, and work onto later in the studio. It is a way of composing using a time-based, fluid medium, but editing in a very deliberate, conservative fashion. The subject of this work is an ongoing project relating to the rise of radical nationalism in Europe over the past few years. I am also working collaboratively on a number of projects; it is a way to shift not only the material, but the conceptual basis for the work, and your starting point. My exhibition At World’s End, with Nick Scammell, has just opened in Peckham on the 27th of February, and explores our shared despair for London through the lens of the capital as a literary city.

19.03.19

Words by Vanessa Murrell

Related

Studio Visit

Arthur Laidlaw

Interview